It is true that authors who took an interest in Madagascar were aware of the institution of slavery. Nineteenth-century Madagascar truly aroused “curiosity in all its forms and at all levels.” Given the current state of research and knowledge about the country, the bibliography regarding Madagascar is substantial. However, we wished to share here the section on Andevo— the word meaning ‘slave’— which, in the Firaketana, seems closer to reality (in the Latin sense of the term).

The word Andevo is a generic term that in the hierarchical Malagasy society designates an individual who has lost his or her rights – in Malagasy, very zo – and who is nothing more than an object before the law. This expression has its counterpart: the one who enjoys rights recognized by a monarchical regime – here of divine right – is an Ambaniandro, a subject before the law. The term is composed of two words: Ambani, which means ‘below’, and andro, which can mean either ‘day’ or ‘the sun’. Here, Andro carries both meanings. In this society, any person who is not a royal subject is therefore a ‘slave’. When slavery abolished in Madagascar following colonisation, the colonial authorities were attentive and insisted on the label of ‘subjects’ when speaking of the Malagasy and addressing them, with the aim of erasing the servile status which, in principle and in the eyes of the law, should no longer exist in a territory that had become French…

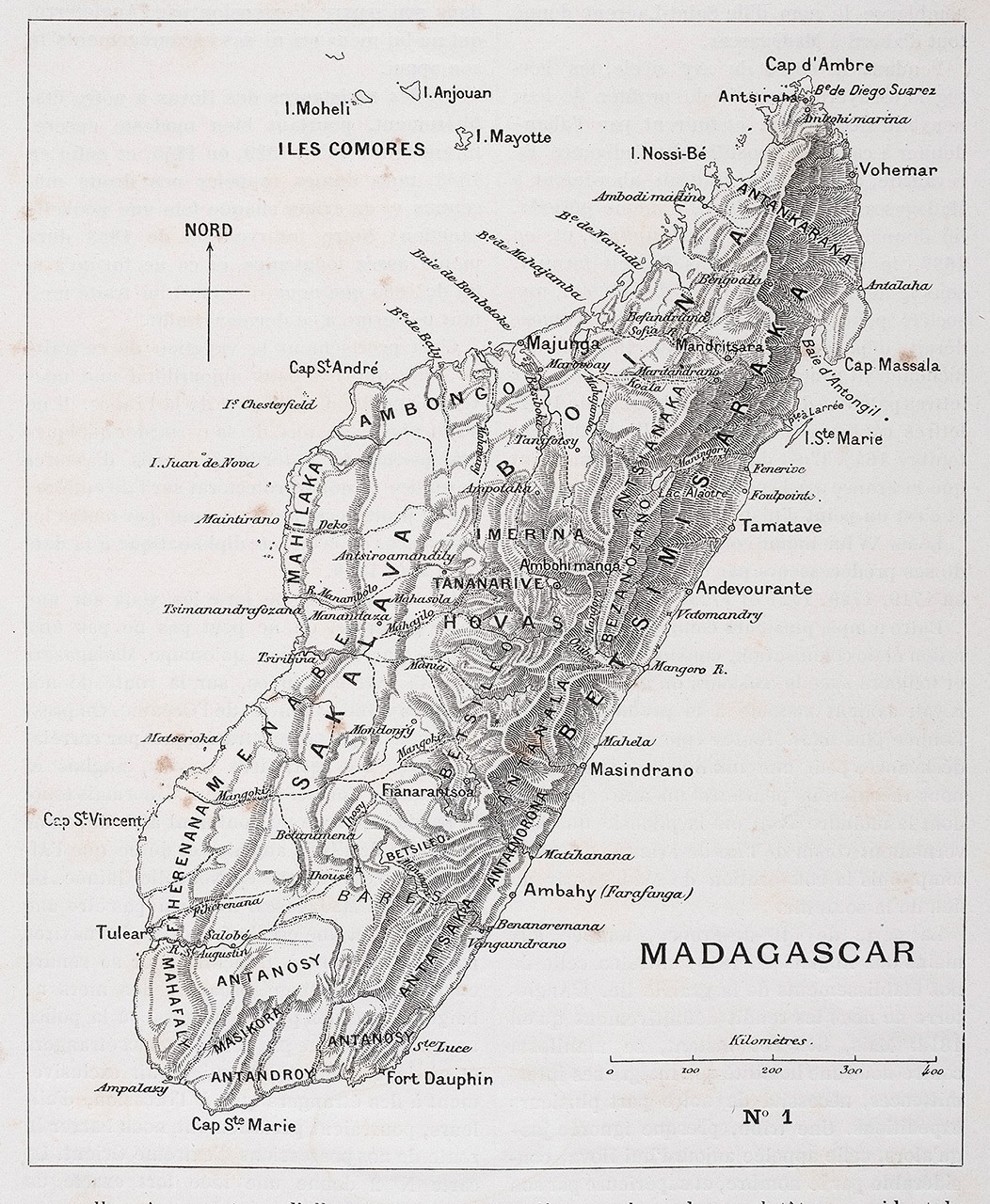

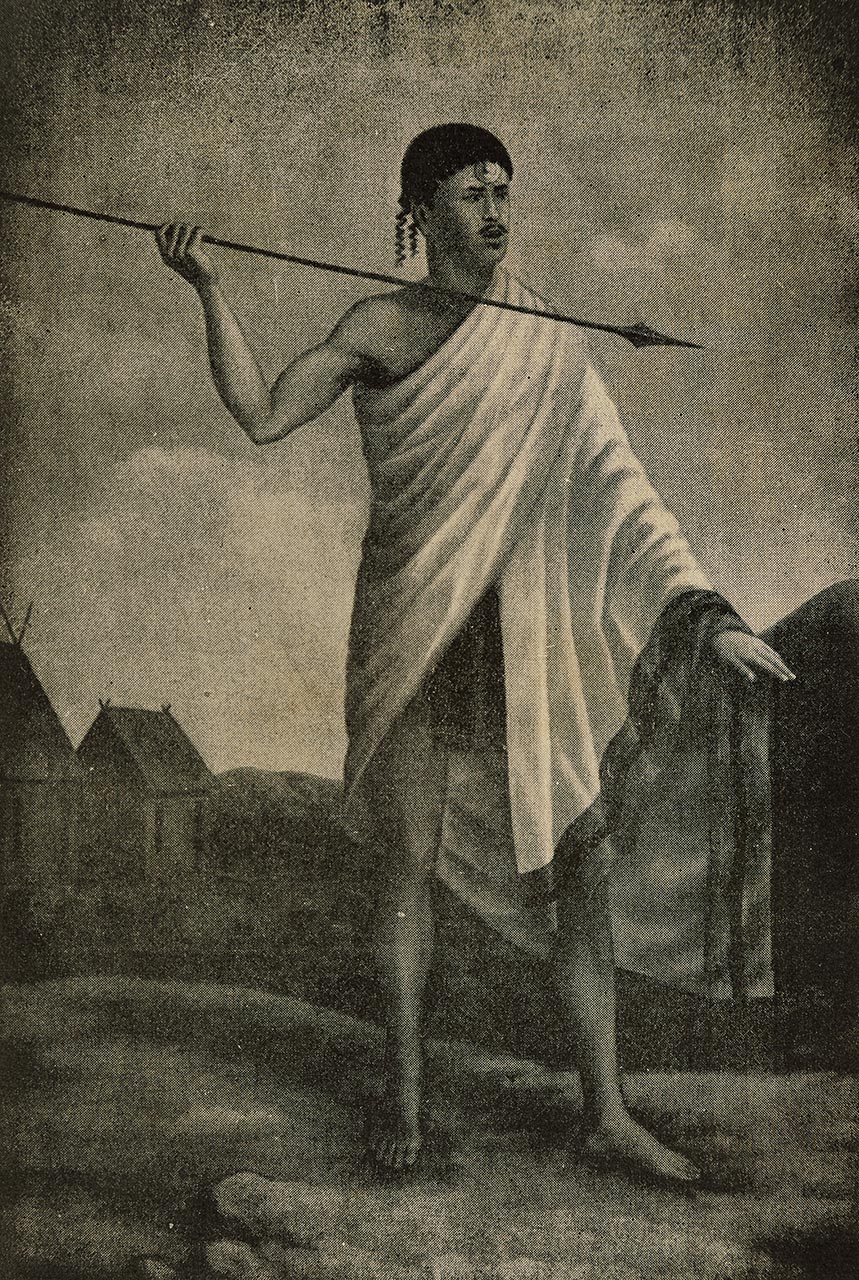

The current article will enable me, with the help of the Firaketana, to share other expressions relating to the servile condition. The entry Andevo begins as follows: “olo-mainty avy tany ivelany na tanindrana teto, izay voababo ny tenany na ny ray aman-dreniny na ny razany ka nampanompoina : mpanompo.” According to the Firaketana, the origin of persons corresponding to this status is either Blacks coming from outside the country, individuals born to slave parents, or else descendants of ancestors who were already slaves. This entry points to either two or three origins of slavery. First of all, the slave trade that was rife throughout Madagascar in the 19th century. The treaty of 23rd October 1817 signed by Radama I (1810–1828) and the Governor of Mauritius, Sir Robert Farquhar, who represented the British Empire, was an initial attempt to halt the export of Malagasy people and the importation of Africans, generally from East Africa and particularly Mozambique. These slaves were objects of exchange between various Malagasy kingdoms, particularly the Merina, Sakalava, and Betsimisaraka, and traders or slave traders from diverse backgrounds. The Antalaotra – semi-Islamic Malagasy – served as intermediaries between the natives and Arabs and Europeans (Portuguese, Dutch, English or French), as well as Americans and Asians, more particularly Indians.

The introduction to the entry Andevo initially gives us two causes for “becoming a slave,” but other causes existed for being “treated as a slave”: spoils of war, birth, judicial sentencing and insolvency.

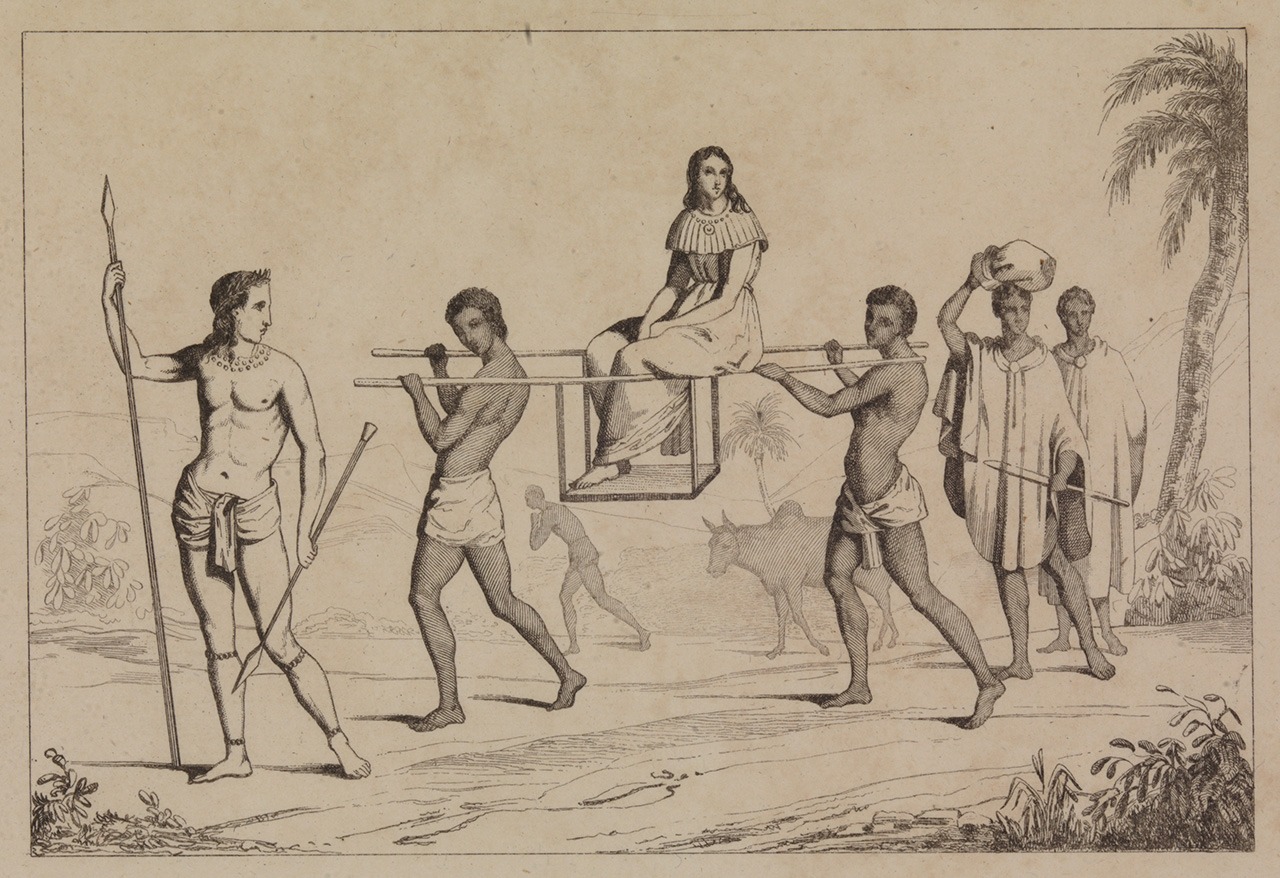

First of all, it must be emphasized that all work to be carried out by human beings was accomplished by slaves. These tasks were distributed according to the wishes of the masters, as well as gender, physical capacity, sometimes personal skills, and even physical appearance. Consequently, slaves working at the Palace were called Andevo-andapa (andevo: slaves; andapa: at the Palace). By contrast, ordinary domestic slaves working in private households were called ‘Andevo-ampatana (ampatana meaning ‘at the hearth’), even though domestic tasks carried out at the Palace and in private homes were essentially the same: upkeep of the house, catering both for daily life and for banquets: we must remember that Malagasy people shared meals at every community gathering. Slaves were therefore responsible for pounding rice, cooking it and gathering firewood. Other tasks included laundry and transporting the masters during journeys (milanja ny tompony).

Apart from transportation, ‘ordinary’ domestic tasks were, in principle, assigned to women. Work was also distributed according to gender, particularly agricultural tasks. Preparation of agricultural land and paddy fields was reserved for men, while women were tasked with sowing and harvesting. Agrarian rites were accessible to both royal subjects and individuals of modest status, as these were of common interest: the communion of the visible world and the cosmos, the invisible world for the preservation of the lineage. This may provide us with a partial explanation for the “milder aspect, compared to elsewhere,” of the servile condition in Madagascar.

Quite simply, our ancestors created another category, that of Andevo-havana (andevo: slaves;‘havana: relatives). This expression referred to members of the extended family (fianakaviambe) who were poor and lacked the means to survive in difficult circumstances.

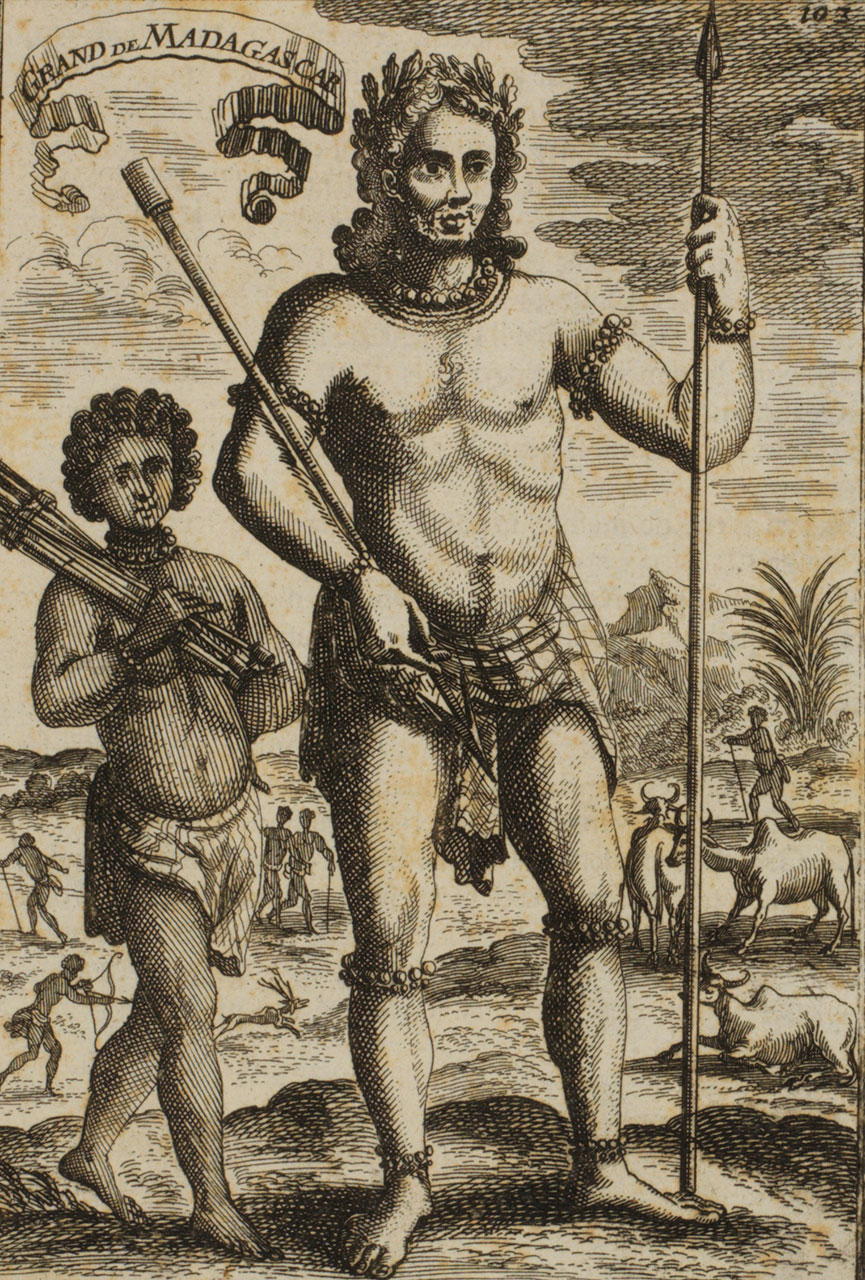

We hope that this article will contribute to moving beyond preconceived ideas, while remaining concerned with preserving truths closer to the servile condition, more subtly referred to as “the resurgence of slavery.” In this section of the article, we can speak more broadly about a social category rarely mentioned in various writings, yet whose members sometimes played roles as important as those performed by the elites in achievements or simple events that contributed to the greatness of these kingdoms. The members of this category were known by various names reflecting their social, cultural, economic, and political importance: the Lehibe (the Great Ones), the Loholona (the Elders), the Hazomanga (the Chiefs, the Primordial), and the Manamboninahitra (Those with honors, particularly high-ranking officers).

We can give two examples.

1-The participation of slaves in palace revolutions

We can refer to at least two such revolutions. These palace revolutions were, amongst other factors, caused by the ambiguity of the laws of succession to the throne of the Imerina, issued by the Queens Rafohy and Rangita in the 16th century, as well as those imposed by King Andrianampoinimerina (1785–1810), and by the culture of political impatience among future Merina sovereigns.

These circumstances caused the palace revolutions that led to royal authority being overturned and involved certain royal slaves, including the Tsimandoa Ramboamamy, during the assassination of King Radama I (1810–1828) on the night of 27-28 July 1828. According to Raombana, in his work Histories, that night saw a revolution and a coup d’état that brought Ranavalona I (1828–1861) to power, described by Simon Ayache as ‘a praetorian-style’ coup, remarkably organized and executed, ultimately sanctioned by the pusillanimity and fear of the masses…”.

According to Raombana, the queen was the main instigator of the coup.

“The king’s being seriously ill, his usual food was prepared in the southern palace and transported to the Tranovola, or Silver Palace. As Radama could not eat, it was the Tsimandoa (royal slaves) who ate in his place: a stratagem designed to keep the people ignorant of the king’s true condition.

When Radama was close to dying, Ramboamamy, one of the Tsimandoa, feared the collective responsibility they would bear if the king died among them, while his family and the people believed he was in good health and simply suffering from a minor ailment. Terrified of being executed by the people, along with his companions, he discreetly approached the king’s wives.

Accompanied by a few ministers, Radama’s wives went to the Silver Palace to see the king and assess his condition.

Raombana insists on the role played by Mavo, Radama’s first wife and future Queen Ranavalona I. “This meeting between Radama and his wives,” he claims, “directly triggered a revolution that completely overturned the Andrianampoinimerina dynasty and Radama, placing the crown in the hands of someone with absolutely no right to it, seizing power through intrigue and promises of rank and wealth to a small group of men.” Yet rereading these events also highlights the crucial role played by the Tsimandoa in the assassination of Radama I. The text emphasises the servants’ concern in the face of the unfolding tragedy. They were also aware of what was wished by Mavo. The latter had not directly informed them of the premeditated crime, but we can question the reaction of Ramboamamy. If the royal slaves had not acted, what would have been the king’s fate? Such political assassinations leave actors, witnesses, observers, and public opinion, both present and future, in disarray. What became of these Tsimandoa?

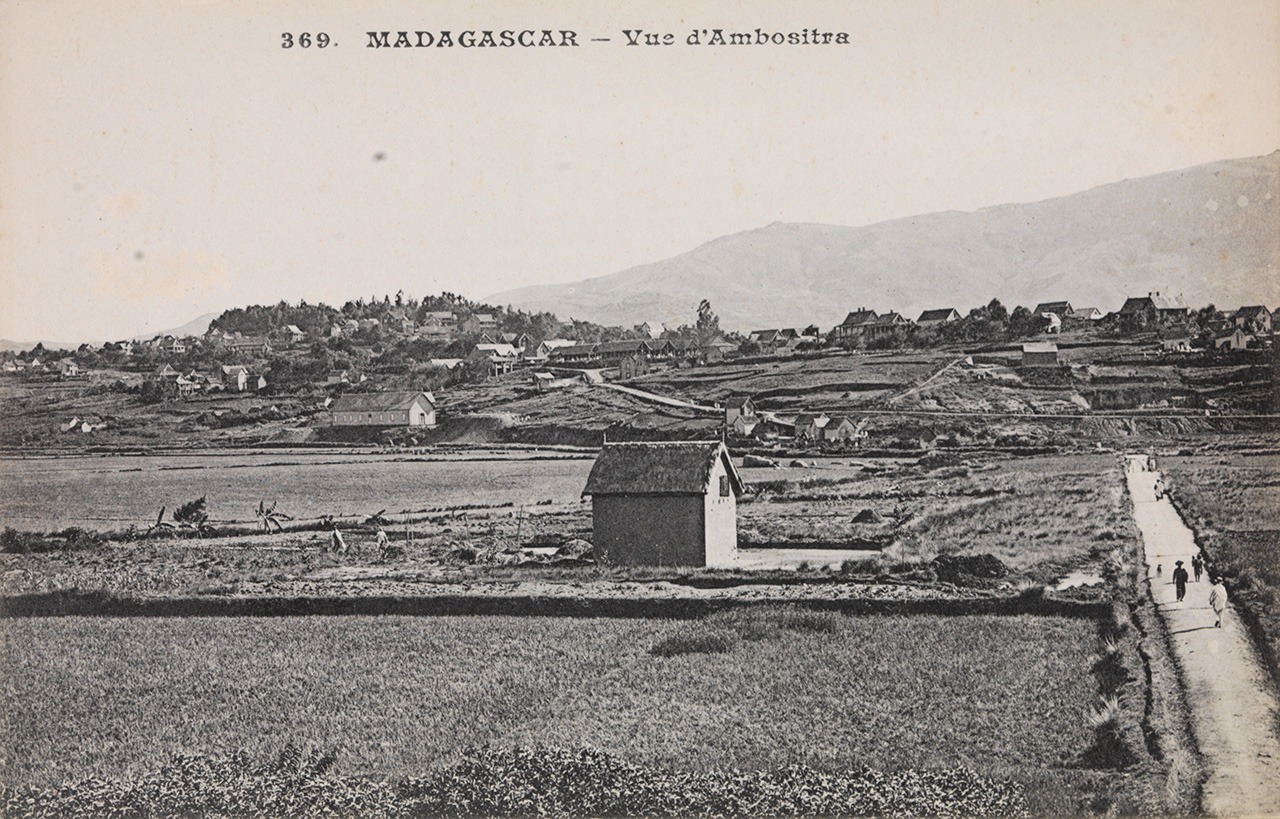

2 – The Participation of a royal slave in the exercise of royal power: Rainisoavahia ‘XII honours’, Governor of the province of Ambositra (1880–1895)

Rainisoavahia ‘12 honours’ served as governor of Ambositra, a major hub in late 19th-century Madagascar (1889–1895), an extremely important post, nearly as important as that of the governors of Toamasina or Majunga. These governors were appointed by Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony to represent the Queen. Their position carried no salary and often exposed them to abuses of all kinds.

“According to oral investigations carried out among elderly informants, Rainisoavahia was an Olo-mainty (Black man)”, more precisely a Tsiarondahy, originally from Tanjombato. Surprisingly, many individuals mentioned in Catholic diaries who assisted priests in establishing Catholicism in Betsileo territory were also Tsiarondahy.

Oral testimonies unanimously praise Rainisoavahia’s governance: “… he was a very good administrator, one of the few who tried to remain impartial, especially regarding missions.” Indeed, he had to manage intense inter-missionary competition, far from easy in view of the different religious congregations present and Ambositra was a strategically significant and thus demographically diverse regions, being a major mining area and so an important hub, during a period when Madagascar had to pay compensation to France following the first Franco-Malagasy war (1883–1885). Rainisoavahia thus enforced compulsory labour for gold mining and faced distrust from various sources, including Queen Ranavalona III (1883–1896) herself. He was ultimately spared by the arrival of the French and continued to exercise in the colonial administration as governor of Majunga, Mahanoro and Manjakandriana.

There was also a hierarchy of royal slaves. They all belonged to the Maintienindreny (literally: ‘the Blacks of the six mothers’). This explains why Governor Rainisoavahia was seen as an Olo-mainty. The distinction was clear: he was a subject of the Queen with full rights and should not be confused with those who had lost theirs for one reason or another. These royal slaves were divided into three subgroups: the Manisotra, the Tsiarondahy, and the Manendy.

The Manisotra occupied the top rank established by Andrianampoinimerina (1785-1810). At the time, the rules of war would place those vanquished on the level of simple objects before the law. During the unification of the Imerina, Andrianampoinimerina had to launch four deadly campaigns before subduing the Manisotra of Ambohijoky in the south of the kingdom. Impressed by their determination, to resist being reduced to slavery, Andrianampoinimerina magnanimously took them as his own servants. Father Callet paid tribute to them, giving a long narration of their resistance in his account of Merina traditions Tantaran’Ny Andriana, describing the fierce confrontations between the Manisotra and Andrianampoinimerina’s warriors.

Here we should also emphasize the character of the Manisotra women in the face of Andrianampoinimerina’s wish to unify the Imerina geographically.

“The attack on the village was among the hardest. King Andrianampoinimerina, in his attempts at conquest, sometimes encountered great resistance; however, no lord of the surrounding areas was truly able to provide efficient opposition to his strategy. If he was held back for such a long time before the rock of Ambohijoky, which served as a refuge for the Manisotra, it was largely due of the virile resistance of the Manisotra ‘Jeanne Hachettes.’

Faced with the women’s courage and tenacity, the king had to mount four expeditions against the Manisotra, employing cunning and all kinds of strategies, with little success: the Manisotra were finally subdued through famine.” Following their surrender, King Andrianampoinimerina made the Manisotra warriors an elite corps in his army.

Who was likely to become Tsiarondahy or Tsiarombavy?

First of all, prisoners of war selected by the King from the spoils of war. They were called Tandapa mainty and were integrated into the subgroup of the Tsiarondahy. They had to be men of confidence, since they were entrusted with the most important messages. Some of them were Tsimandoa. One should therefore not be surprised that the future Ranavalona I entrusted the supervision of royal meals to Tsimandoa…! The example given by the Firaketana is that of those defeated at Kiririoka. One third of the defeated were given to the King and two thirds to his subjects. These two thirds became ordinary slaves, Andevo or Harena (literally: goods). Having the status of royal property, they were also called Tserok’Andrianampoinimerina (literally: the sweat of Andrianampoinimerina). According to the explanation given by the Firaketana, this designation was due to their belonging to the King as soon as they surrendered, which was perhaps the case. But we can also suggest other explanations. This group of people had been so faithful to the King that they must have been given their nickname by other members of the population. Whether out of mockery, envy, or simple admiration, this sobriquet was later appropriated by them, as they felt they were in a position of strength or defence against all odds in the highly hierarchical society.

This third group bears the name that evokes their defensive tactics.

When attacked by the Andrianampoinimerina, the Manendy attempted to defend themselves by pouring hot stones onto their adversaries. However, they were not able to fend off the Kings warriors and were forced to admit a second defeat. The king of the Imerina then captured them, and they became ‘Manisotra’: royal slaves. According to Father Callet, “The Manisotra and Manendy remained free families like the Ambaniandro, while still belonging to the category of ‘the Blacks of the six mothers’. The place of residence of the people of Manisotra was Anativolo. They were associated with the Mandiavato, and carried out the same tasks.” These royal slaves thus shared the rights and duties of the Ambaniandro, like the Vakinisisaony and the Mandiavato, that is to say subjects before the law or royal subjects unlike the Tsiarondahy, who could not own rice fields.

The finest among these slaves were integrated into the sub-group of the Tsiarondahy and became Tsimandoa under Radama I!

We could emphasize the relatively humane treatment of royal slaves. If we refer to the accounts left by those who had witnessed and observed their daily lives. however, we will, for once, suggest a concept which defines both the status of these royal slaves towards the end of the 19th century, immediately preceding the arrival of the French with their new values. This concept is expressed through the word TANDAPA.

Tandapa literally means “those who live in the Palace, those who surround the King or Queen” or simply courtiers, with all the connotations related to the term. Instituted by Andrianampoinimerina at the end of the 18th century, the status of ‘slave’ implies many forms of negation at all levels. Towards the end of the 19th century, a prince of royal blood, such as Prince Ramahatra XV ‘of honours’, proudly identified himself as a Tandapa, when he needed to give his identity before the doors of the palace to the guards, who were themselves Tsiarondahy-Tandapa. Father Callet concluded one of his pages on the Tsimandoa with the simple phrase: “They became the Tsimandoa, still spoken of today.”

André, E.C., « De l’esclavage à Madagascar ». A. Rousseau, 1899, 276 p.

Ayache, S., « Raombana, l’Historien (1809-1855) », Ed. Ambozontany, 1976, Collection Gasikarako, 510 p.

R.P. Callet, « Tantaran’ny Andriana », traduit par G.S. Chapus et E. Ratsimba « Histoire des Rois » 1874, 576 p.

« Fanandevozana, Esclavage à Madagascar ». Actes du Colloque commémorant le centenaire de l’abolition de l’esclavage à Madagascar (24-26 Septembre 1996), Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie –Université d’Antananarivo

« Firaketana ny Teny sy Zavatra Malagasy », en abréviation « Ny Firaketana », première encyclopédie malgache, sous la direction du Pasteur ravelojaona et Rambeloson, entrées A à L, 1957

Raombana, « Histoires », 3 tomes, Ed. Ambozontany, Collection « Gasikarako »

Ravelomanana, J., « La vie religieuse (1880-1895) » ; Mémoire de Maîtrise-Département d’histoire-Université de Madagascar-1971, 150 p.

Ravelomanana, J., « La Femme et la Politique avant 1896 », Ministère de la Culture et de l’Art révolutionnaires, Imprimerie nationale, 1985, 63 p.

Ravelomanana, J., « L’esclavage à Madagascar. Généralités et Particularités », Revue Historique de l’océan Indien N 13, 2016, p. 432-437

Savaron, C., « Mes souvenirs à Madagascar avant et après la conquête (1885-1898) », Tananarive. M.A.M. XIII, 1932, 328 p.