Before being colonised by the French, Madagascar appeared to Europeans working on the island as a “country of slaves”, given that slavery was a major institution for fulfilling economic and social needs, and also considering the large number of persons belonging to this category of the population. In fact, among the social categories in Imerina, slaves represented the largest group. In 1896, according to Resident General Laroche, in Tananarive there were 22,916 slaves out of 43,028 inhabitants: 53% of the total population of the capital. During the period of the Kingdom of Madagascar, slavery remained a structure of economic and social organization of benefit to free men. In order to better organize the system, Queen Ranavalona II (1868–1883), through Articles 39 to 49 of the Code of 305 Articles promulgated in 1881, established a system to control the employment of slaves by private individuals.

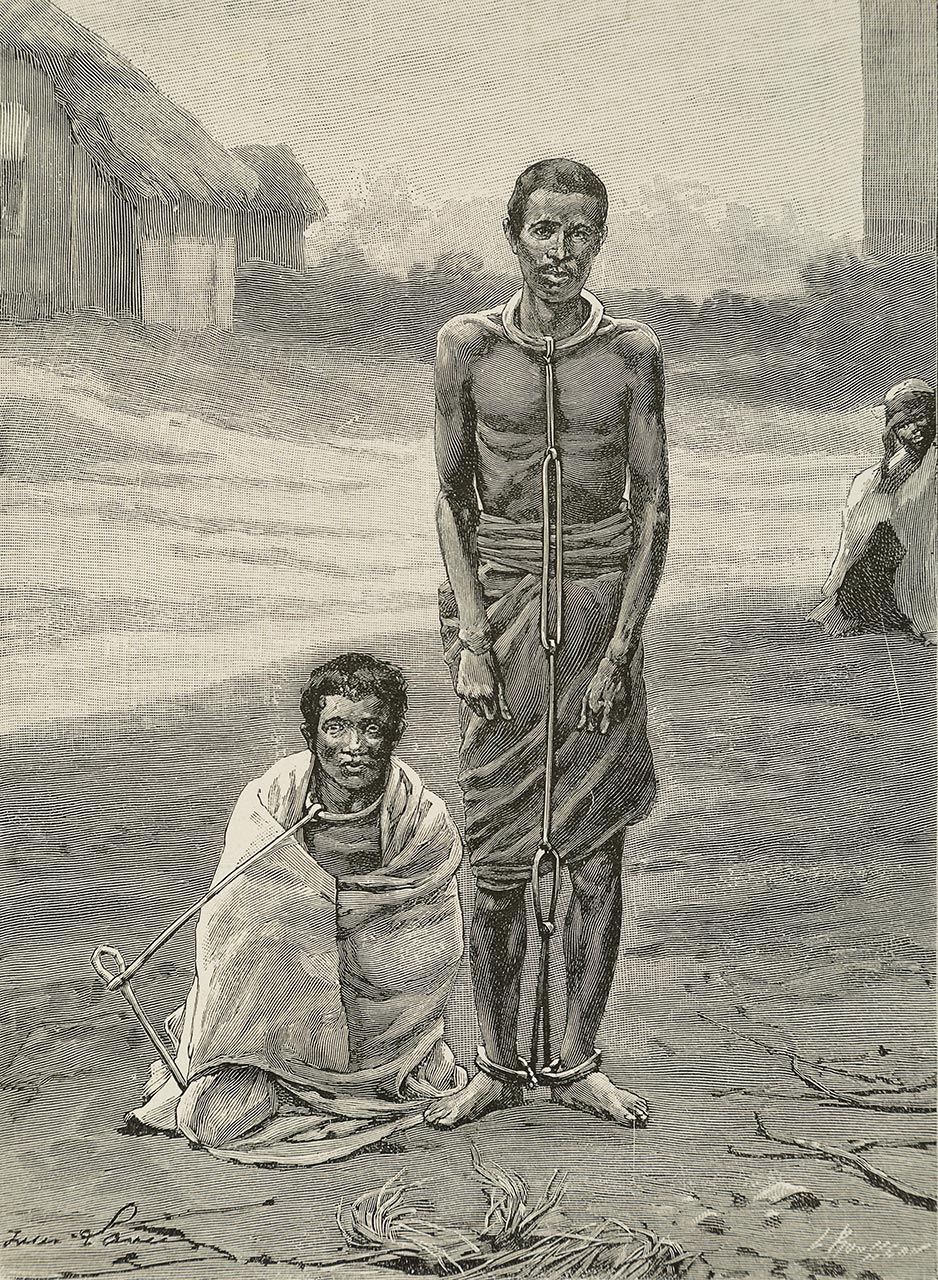

Generally speaking, the latter could purchase slaves only with the aim of employing them for various types of work on their estates or for their own interests. From a legal standpoint, the ‘andevo’ (slave) represented goods or a commodity for his or her master. Slaves could thus be sold, rented out, pledged, or be the object of all kinds of transactions, since they enjoyed neither civil nor political rights. They could not bring legal action or appear before the courts. In the slave’s existence, he or she could not own property and could acquire goods only on behalf of his or her master.

In Imerina, before colonisation by France, slavery remained a means in the hands of the Andriana and other free men such as the Hova for working their land or agricultural estates. The andevo (slaves) remained economic instruments in the hands of their masters, who held manual labour in deep contempt. They carried out domestic tasks, cultivated and worked the land to produce food for the purpose of meeting the needs of the masters and their families, or they carried out paid labour on behalf of their masters. In short, slaves constituted the labouring category of the population. However, for some, the working conditions were far from harsh, as their masters required them to perform only reasonable tasks, leaving them ample leisure time.

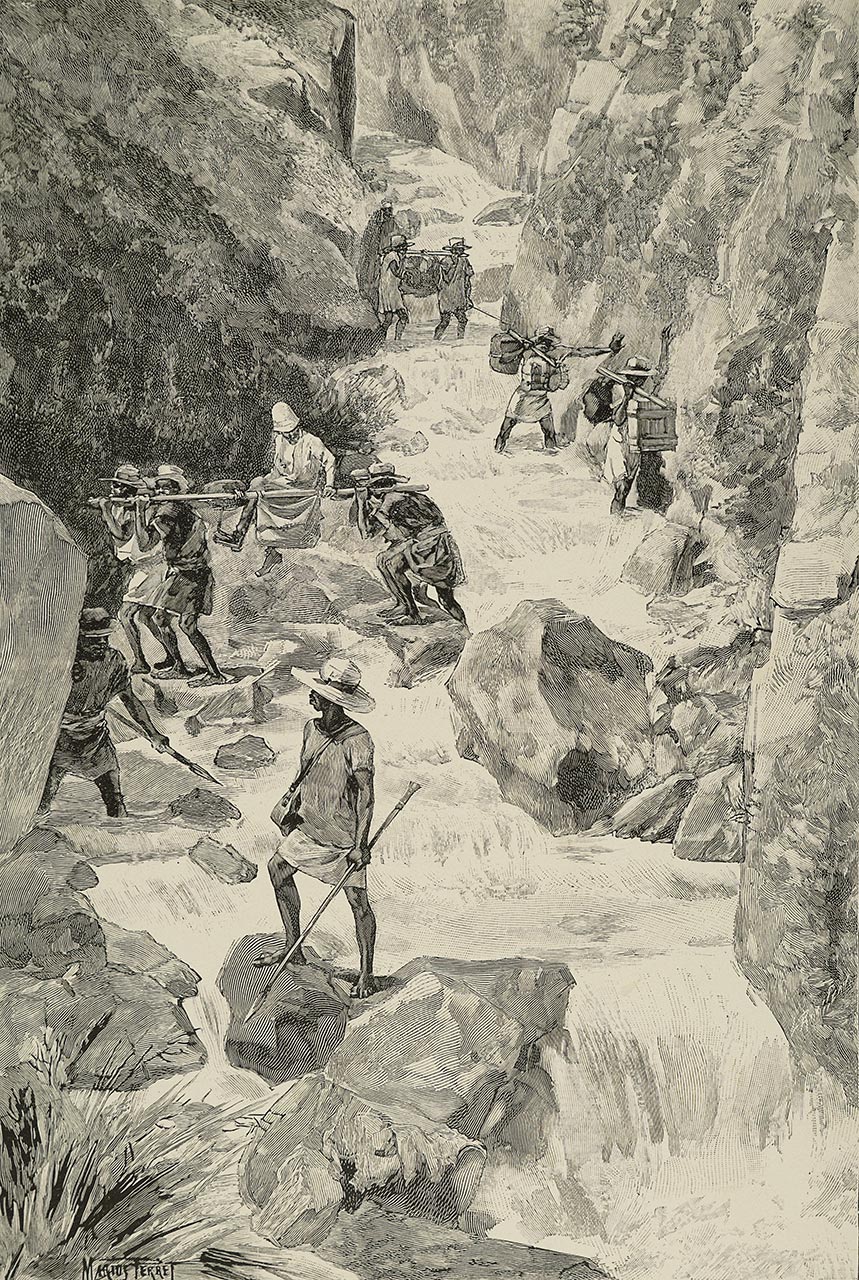

In each a family, there was a true division of labour among the slaves. First, there were the domestic slaves. Next came the agricultural slaves, greatest in number, followed by the herding slaves, responsible for guarding and caring for livestock, the commercial slaves, generally the most intelligent and enjoying real independence and finally the porter slaves, whom their masters often rented out to private individuals in exchange for wages, of which the slaves retained a portion. These qualifications and divisions of labour applied mainly to male slaves, while their female counterparts experienced different conditions. Female slaves constituted, in a sense, luxury slaves, as they were most often employed inside their master’s house or accompanied their mistress on her outings. Sometimes they followed their master outside Imerina, serving him as ‘tsindry fe’ (literally “thigh-pressers”), or concubine slaves. In general, ‘tsindry fe’ slaves were accepted by the spouse, who adopted this attitude in order to avoid her husband setting up with local women. This situation particularly concerned Merina officers sent to settle in conquered provinces and carry out administrative and military duties.

The living conditions of slaves varied from one master to another. If the master was of modest means, the slave raised in the household was often treated more or less equally with members of the family. A slave whose master was not wealthy, was subjected to arduous tasks. A rich and powerful master who owned many slaves would often grant relative freedom to the latter. For the first category, slaves represented an extension of the family, whereas for the other two categories, some masters made their slaves work hard in order to enrich themselves by taking one-third or one-half of their wages. Even though slaves were property belonging to their masters, they were generally well treated, reflecting the “humanist” ideas of most masters. According to Calixte Savaron, among the Merina,

bad masters were rare. The Hova is patient and rarely loses his temper; he never struck a slave with his foot or hand. The idea never occurred to him; it would have been beneath him. If he had to resort to punishment, after several warnings, he justified it before the family and the other slaves. The slave was struck with a switch or an ox sinew. He could be punished with irons when the offense was serious, for example theft outside the household; when the honour and responsibility of the master were at stake, there was a customary procedure and courts to deal with this.

At the end of the 19th century, the good behaviour of masters toward their slaves was noted by other European authors who observed the structure of the Merina slave society. According to Ed.-C. André, “the master considers the slave as one of his own. This slave is indeed his object, his property, in the same way as his rice field or his ox, but an intelligent thing, capable of interest and affection. (…) At all times, Malagasy slavery was distinguished by its patriarchal character.”

In the Merina society, as the slave represented wealth for his master, he benefited from the best attentions of the latter. According to Dr. Charles Ranaivo, vice-president of the Committee that presided over the organization of the festivities held in Tananarive on 8 and 9 October 1909, to mark the laying of the first stone of the monument intended to commemorate the promulgation of the decree [of 3rd March 1909] on Naturalization:

Under the Hova [Merina] monarchy, (…) the true slave was happier than the free man because he depended on only one master, and because this master had no interest in losing or destroying his property. The free man had to endure all the exactions and vexations [of the royal authorities]. Nothing belonged to him; he had no rights.

However, since the slave was his master’s property, the latter could use his status as owner to enrich himself at the slave’s expense. Thus, for a slave employed as a porter, the master might not be satisfied with merely taking his share of the wages, but might also seize the gifts the slave received. Worse still, certain unscrupulous masters did not hesitate to appropriate the property of their slaves upon their death, thus practicing ‘manararao-paty’. In practice, as soon as a master learned of the death of his slave, he declared himself the sole heir. He seized all the deceased’s savings and also took the money from the gifts made to the deceased slave’s relatives during the funeral. In general, slavery remained an economic and social instrument for carrying out various forms of labour: domestic work, agricultural labour, or porterage. As a result, for Europeans who lived in Madagascar in the 19th century, a Malagasy without slaves was considered very miserable and afflicted by great hardship.

In the 19th century, the leaders of the Kingdom of Madagascar adopted the system of slavery to solve the problem of labour and all related issues. The institution was abolished in Madagascar through the decree of 26th September 1896, issued by the Resident General. With this measure, the colonial authorities sought to encourage Malagasy people to engage in salaried labour for those employed by private individuals, particularly French settlers.