On 19th September 1888, lieutenant E. Mockler, British Consul for Muscat in the Sultanate of Oman, recorded the personal account of a 15-year-old adolescent called Khamis Bin Nasseb Mahyawa, who told him that several days previously, he had taken refuge on board a vessel of the Royal Navy, in order to escape from slave traders that had captured him in Zanzibar. The testimony of the young boy Khamis is one of the few of its kind in the archives, which contain a very limited number of accounts given by victims of the slave trade. It throws light on the main characteristics of the trade, as well as the role played by the Royal Navy in repressing it.

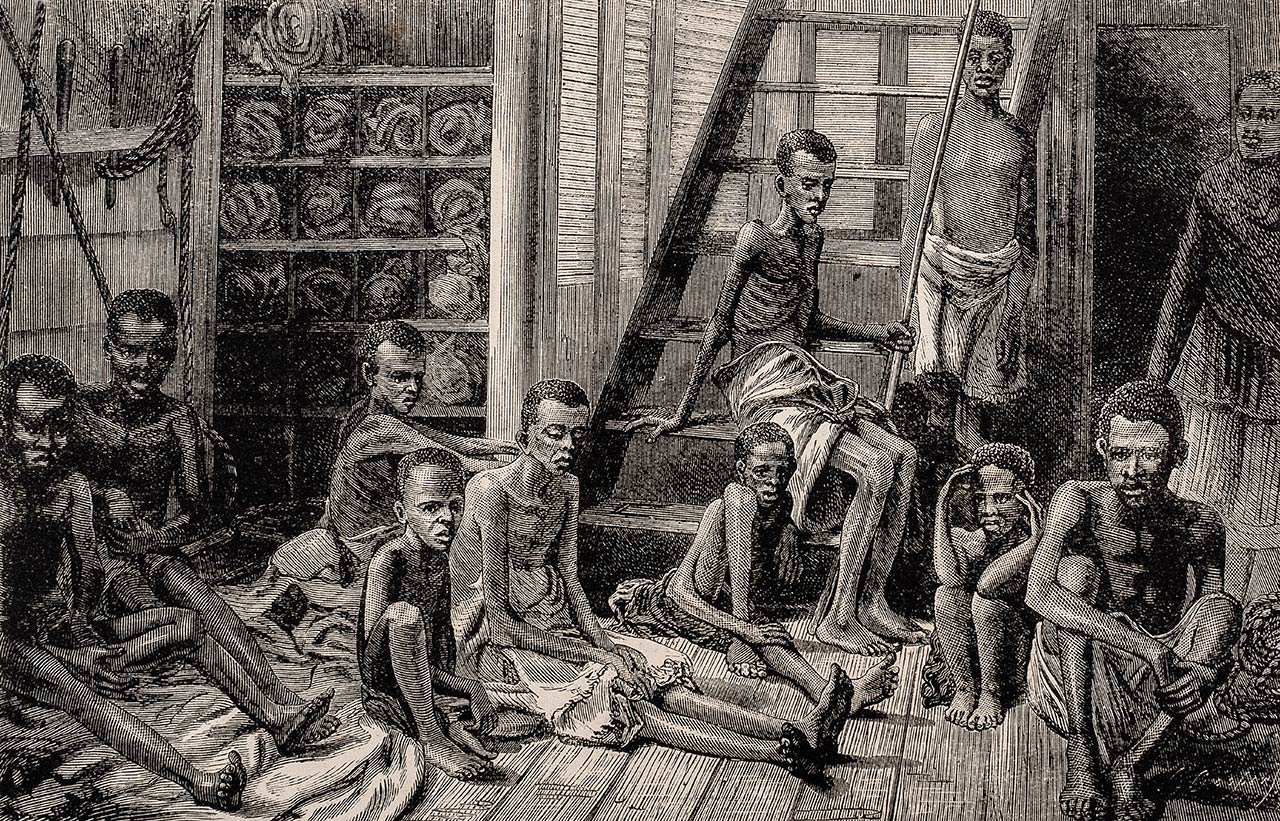

Khamis tells how, as a young boy, he was captured with his family in the region around the Great Lakes of Africa, then taken by force to the coasts of East Africa, before finally being sold to the owner of a plantation in Zanzibar, where he was enslaved. Emancipated following the death of his “master”, he became “a free man”, until being captured once more by slave traders operating in the Persian Gulf, who took him on board a vessel sailing for Bagamoyo, a key trading port on the coast, separated by a very narrow strip of sea from Unguja, the main island of the Sultanate of Zanzibar. After that, Khamis, along with 29 other slaves, endured dreadful treatment. First of all, they were shipped across the Indian Ocean on board another vessel a ‘bungala’, one of those dhows with triangular sails and narrow hulls common in East Africa as well as in Arabia during that period. They finally moored in Sour, another important trading port situated at the mouth of the Persian Gulf in the Sultanate of Oman. Khamis then gives an account of how one day when the ship was anchored not far from the port of Muscat, he took advantage of the laxist attention of his jailers. Spotting a vessel of the Royal Navy, Khamis dived overboard and swam up to it, asking for shelter and claiming his freedom.

Far from being an isolated incident, the account is a typical example of the many cases of fugitive slaves picked up by the Royal Navy during the second half of the 19th century. It shows that the young adolescent was astonishingly aware of the role played by the British Navy in repressing the slave trade. He knew that embarking on board a vessel of Her Majesty’s navy would enable him to escape from his condition as a slave. There was such a large number of fugitives like Khamis that in 1875, the British Admiralty prohibited Her Majesty’s sailors from helping them, for fear of creating tensions with allies of Britain in the Indian Ocean: States whose prosperity (dates, pearls, ivory and cloves) largely depended on this servile workforce. The British also wished to limit their commitment to maritime operations against international slave-trading, while at the same time avoiding the issue of the legal nature of slavery within sovereign States. However, this writ issued by the Admiralty was very soon abandoned under pressure from violent opposition by the public and Members of Parliament in Westminster, mobilisation reflecting the unprecedented force of the abolitionist current in British politics as from the early 19th century.

While in the 1880s vessels of the Royal Navy were known for their commitment in the fight against the slave trade, this had not always been the case. Until its abolition by Great Britain (1807), then by France (1817-1831), the slave trade in the Indian Ocean was indeed mainly in the hands of Europeans. However, after the abolition of slavery in the British (1833), then in the French colonies (1848), and while the slave trade was in decline in the Atlantic in the years between the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the abolition of slavery in Brazil (1888), naval operations against the slave trade organised by the European powers were reinforced.

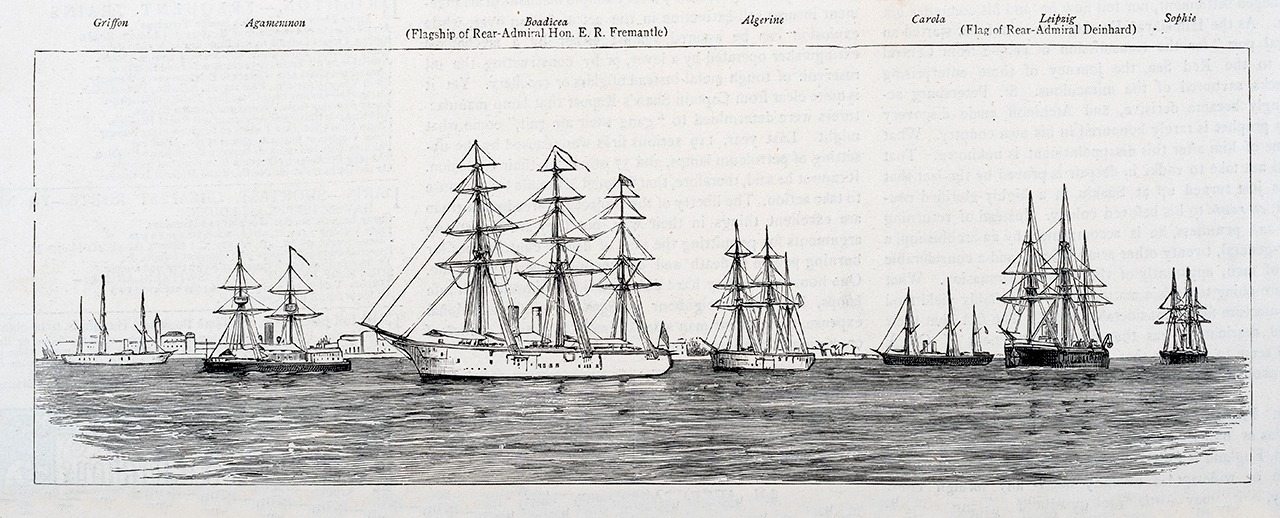

Around 1860, the British naval base in East Africa consisted of “seven to twelve vessels” patrolling “along the eastern edge of the Indian Ocean down as far as the Cape of Good Hope”. Its main mission was to secure the maritime routes to India, jewel of the British Empire. The fight against the slave trade was only a secondary objective, aimed at completing the mission taken on by Great Britain across the world’s seas since 1807.

Nevertheless, in 1873, in a document aimed at the general public, captain G. L. Sulivan gave an account of his campaign in the Indian Ocean during the 1860s, emphasising the extent to which “the means for putting an end to the slave trade were inadequate.” However, thanks to reports published by the British Parliament and works disseminated for the general public, British naval officers like Sulivan were able to improve the situation to a certain extent. This strategy mainly bought its fruits following the diplomatic visit to Zanzibar made by Sir Bartle Frere in 1873, leading to the signature of a treaty abolishing the slave trade along the coasts of the Sultanate. The means were reinforced during the naval blockade of Zanzibar (1888-1889), the aim being more to repress an anticolonial rebellion than to truly put an end to the slave trade, during this period when the scramble for African territory was at its height. In any case, as many historians have pointed out, British vessels engaged in the fight against the slave trade did not have the means to truly put an end to the trade, even though they contributed substantially to reducing it. From 1860 to 1890, British naval vessels captured 1,000 Dhows, freeing approximately 12,000 slaves (a total of 22,000 between 1807 and 1888), while it is estimated that between 800,000 and over 2 million persons were victims of the slave trade during this period.

Also, we can point out that the majority of those who, like Khamis, were ‘freed’ by the Royal Navy became victims of new forms of colonial servitude, either in the form of an “apprenticeship” (becoming a ward at the disposal of the State or a private person), or that of “contractual (indentured) labour”, reflecting the very difficult conditions of Indian or Chinese coolies. Virtually all “freed Africans” in the Indian Ocean became “indentured labourers”, working either in the army, for religious missions, public works, colonial plantations or as domestic workers. Some of them even worked as interpreters or sailors for the Royal Navy and actively played a role in the fight against the slave trade.

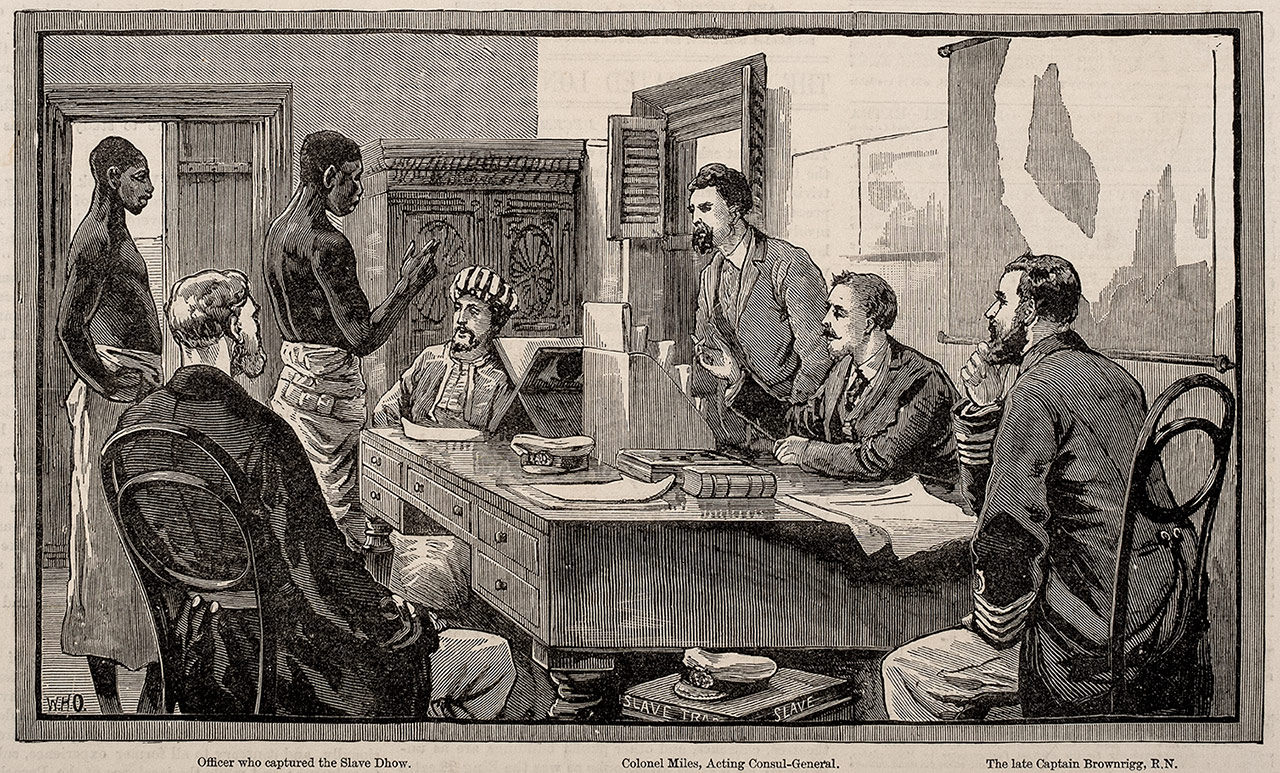

In the Indian Ocean, as in the Atlantic, repression of the slave trade carried out by the Royal Navy was, nevertheless, a legal and political revolution. The struggle was, indeed, strictly controlled by the Parliament, the Admiralty, the Foreign Office, and the consular authorities in the countries concerned. The aim was to avoid all capture of “slave trading” vessels being interpreted as a breach of freedom to sail the seas (a guarantee for world trade) or as an infringement of the sovereignty of States (any vessel flying a flag being considered as an incarnation of the sovereign State concerned).

To fight against the slave trade in times of peace, Britain had declared the right to visit (inspect) vessels suspected of being involved in the trade, with the signature of a certain number of bilateral treaties authorising boarding, then capture, followed by the destruction of the vessel concerned. Originally, however, in application of international law, the right to visit and capture a commercial vessel was only applicable in times of war. The aim was to avoid any foreign interference in a conflict, thus preserving the sovereignty of States. The inspection and seizure of slave-trading vessels thus opened the way to a new form of interference, in application of humanitarian values not yet inscribed under international law.

Any capture of a vessel taking place in the context of repression of the slave trade thus had to be carried out in application of a strict legal and political framework. Capture had to be approved by a court coming under the Vice-Admiralty (a court responsible for judging maritime conflicts) or by a Joint Commission (a court set up under a bilateral agreement between two nations). In the Indian Ocean, any naval officer carrying out the capture of a ship was to sail as quickly as possible to a port harbouring one of the courts of the Vice-Admiralty: Cape Town, Mauritius, Aden, Bombay, or Zanzibar as from 1869. As indicated in the table below, the court of the Sultanate witnessed important activity during the second half of the 19th century, with 7,819 slaves being “freed” out of a total of 12,000 freed between 1860 and 1890 in the Indian Ocean.

| Years | Number of dhows captured and cases tried by the Vice-Admiralty Court of Zanzibar | Slaves ‘captured’ then ‘freed’ |

| 1867-1874 | 214 | 4 698 |

| 1870-1875 | 89 | 2 118 |

| 1880-1884 | 117 | 1 003 |

However, application of the right to visit a vessel was open to abuse. Not only did these cases discredit the nature of the mission carried out by the Royal Navy, but they could also lead to diplomatic crises with the countries whose vessels had been abusively boarded or destroyed. In 1868, for example, the Sultan of Zanzibar Seyyid Majid wrote to the British Consul Henry Adrian Churchill to complain about the capture and destruction of dhows that he considered to be a breach of his sovereignty and of international law. Between France and Britain, the application of the right to visit led to a number of crises. These recurring incidents led to exceptional tensions in relations between the two countries during the 1840s in the Atlantic, then during the second half of the century in the Indian Ocean. In fact, France still refused to grant the British Navy the right to visit vessels flying the French flag, except between 1831 and 1833 in the Atlantic under limited conditions. Indeed, Paris considered that boarding one of the vessels flying its flag by the Royal Navy was an unacceptable humiliation, aimed at limiting French sovereignty. On the other hand, London accused France of allowing the slave trade to proliferate under the shelter of its flag, thus preventing the success of its “noble humanitarian mission”. France retorted that applying the right to visit by the British Navy was simply an underhand means of asserting British naval and colonial supremacy. Towards the end of the century, conflicts between the two powers became increasingly frequent.

Among the incidents concerned, we can mention the case of the Fath el Kheir in 1893. The vessel was arrested in the port of Zanzibar by H.M.S. Philomel with 77 slaves on board, or that of the Diriki in 1900, as well as the Fath el Kheir, both also seized with a large number of slaves on board. A number of random boardings were also carried out. In September 1897, the Fath el Kheir in Mombasa and the Majunga in Pemba were stopped and inspected by the Royal Navy, but were in no way involved in the slave trade. Such incidents continued to perpetuate the vicious circle of tensions between the two rival colonial powers, reaching their peak at the turn of the 20th century.

In 1903, five owners of “French dhows” originally from Sour were arrested by the British Navy, then tried and imprisoned by the Sultan of Oman. In order to avoid a conflict between Paris and London, the case had to be to be brought before the newly formed Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, since these men, as well as their vessels, were considered to be “French subjects”, thus coming solely under French law. For Paris, it was a question of sovereignty, while for London it concerned the sovereignty of Oman and consequently the right to visit granted to the British Navy. The court issued its ruling on the 8th August 1905 concerning “the case of the dhows of Muscat”. Within the new political context of the Entente Cordiale (1904), this ruling put a final end to the violent crises opposing the two countries in the Indian Ocean. While giving a nation the right to grant vessels of its choice authorisation to fly its flag, and thus protecting the sovereignty of States, the ruling of the court did, however, limit the action of dhows, in application of ratification by France (1892) of the Brussels Act of Convention (1890). The aim of this international treaty was indeed to fight against the slave trade in the Indian Ocean, granting the signatories the universal right to visit “slave ships”. In the context of the new European colonial momentum in Africa, the purpose was also to place western imperialism under humanitarian auspices and international law, thus making it legitimate.

While historians continue to debate the historical meaning behind British repression of the slave trade in the Indian Ocean, it is established that the action of British vessels contributed significantly to reducing the trade without, however, putting an end into it. The historian Matthew S. Hopper has demonstrated that the slave trade only declined in the Indian Ocean during the 1920s, when “the commerce of dates and pearls with Arabia [collapsed] due to globalisation”.

On the other hand, the contribution of Britain was decisive in determining the status of the slave trade in context of international law. The historical experience of the Royal Navy did indeed inspire articles 99 and 110 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982), which made illegal the transport of slaves, then established a universal right to visit vessels suspected of being involved in the trade.