This initial abolition never affected Martinique, as its English occupiers at the time prevented the application of any ‘French law’. This first abolition of slavery was revoked in 1802 following Bonaparte’s success in reclaiming Guadeloupe through a bloody conflict. However, this was never achieved in Saint-Domingue, as the colony proclaimed its independence on 1st January 1804, following the surrender of French troops at Vertières on 18th November, 1803.

In the Indian Ocean, things were quite different: voted by the French Convention on 16 Pluviôse Year II (4th February 1794), the first abolition of slavery was never applied there and, during the revolutionary period, slavery continued just as before. And yet, unlike Martinique, these French islands were not under foreign occupation, even though maritime routes were almost entirely under the control of the British fleet. The reasons why abolition was not applied were purely internal, specifically connected to the region’s system of slavery.

First of all, unlike in the West Indies, the plantation system was less widespread : it was set up during the first decades of the 18th century, initially on modestly sized estates, although larger domains slowly developed. This therefore led to lower land concentration and consequently fewer slaves .Sugar cane, whose intensive farming has always been closely linked to the rise of mass slavery, took more time to develop here, slowly replacing coffee plantations which required much less manpower. Slavery was certainly present from the first agricultural settlements, but the numbers involved were much lower than on the Caribbean islands .

This unusual characteristic should not be idealized , for another important fact resulted from this: like elsewhere, victims would refuse to submit to their enslavement in a variety of ways, but here there were never any large-scale uprisings or large communities of escaped slaves. The 1811 insurrection in Saint-Leu was somewhat of an exception , even if it said much about the constant tensions inherent across slave plantations . Above all, resistance to slavery manifested itself in less spectacular ways, such as the continuation of cultural practices from the slaves’ homelands: Madagascar, East Africa, the Comoros and India. Storytelling, music, dance, and the addition of their own religious practices to standard Catholic rites … And so, this resulted in a culture which was unique to Reunion’s slave society, and the failed revolutionary abolition of 1794 only served to strengthen this particularity. The fact that Reunion missed out on both this abolition and the consequently huge impact of Haiti’s independence on colonialism in the West Indies also meant that the island never suffered from the violent re-establishment of slavery in 1802.

Between the beginning of the 19th century and the French abolition of 1848, the colonial world of the Indian Ocean underwent two major changes that had a profound impact on slavery.

First was the prohibition of the slave trade. First imposed by England in 1807, then extended across all powers present at the signing of an Additional Act at the Congress of Vienna in 1815: Reunion, now the only French colony in the region, could not ignore this new situation. Any importation of new slaves would have to be ‘clandestine’ and illegal under international law, even if it was still allowed to continue for a long time.

The second major change came when England proclaimed the abolition of slavery in its colonies in 1833. As the colonial Indian Ocean was then almost entirely British, Reunion Island remained the only place in the area which continued to have slaves.

These two facts should not be omitted when explaining the ‘peaceful’ process of 1848. Admittedly, the French colonists of Reunion Island remained firmly attached to the practice of slavery, which they considered to be a vital necessity for running their plantations. However, aware of the local and international context, how could they continue to stand in the way of an abolition law voted in Paris, as they had done between 1794 and 1802? For their part, the slaves themselves held no yearnings for insurrection. In Martinique, a slave revolt at Le Carbet actually led to abolition being brought forward: the decree of 27th April was certainly well-known on the island, but waiting for the end of the two-month period prescribed by the government would have risked triggering this much-feared general uprising. Thus abolition became effective there from 22nd May 1848, a result that can be explained as a consequence of the revolt rather than any freedom ‘granted’ from Paris.

In Reunion Island however, the process of abolishing slavery stayed very much within the framework laid down by the provisional government.

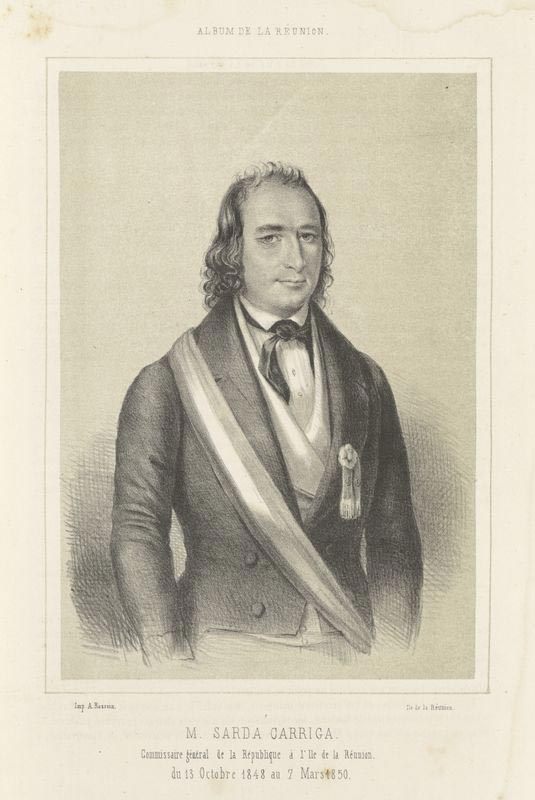

Joseph Napoleon Sarda, known as Sarda-Garriga, was appointed ‘General Commissioner of the Republic’ for Reunion Island with the explicit aim of implementing the decree of 27th April 1848 to immediately abolish slavery in all the French colonies.

After a long journey, he arrived on the island on 13th October. By this date, abolition had already been applied in the Caribbean colonies. Despite pressure from colonists who requested a reprieve of a few months, Sarda-Garriga applied his instructions to the letter, enacting a decree on 18th October which would be enforced two months later, in accordance with official instructions. This deadline was scrupulously respected, and no early abolition was self-proclaimed by anyone on the island. New labour laws were drawn up, ensuring that work contracts were compulsory for the ‘new Freedmen’, legally binding masters to their indentured workers. This was to prevent any risk of halting production (especially sugar), which would have been caused by any former slaves suddenly proclaiming themselves ‘free’. The choice was made to replicate the form of ‘compulsory labour’ for Freedmen introduced by Sonthonax in Saint-Domingue during the first abolition in 1793.

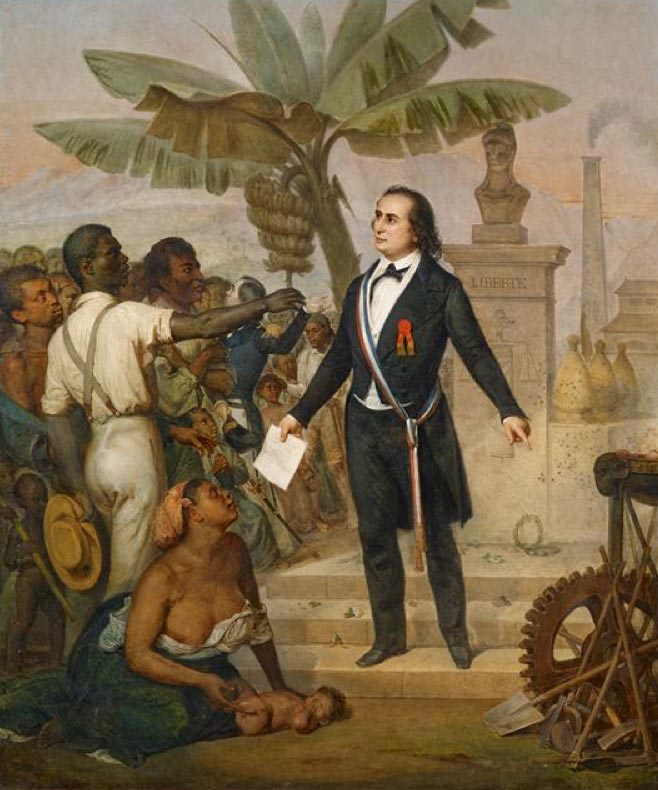

When the two-month period was over, Sarda-Garriga finally proclaimed the complete abolition of slavery on 20th December 1848 with a solemn proclamation, beginning with the following sentence: “My friends, the decrees of the French Republic have been executed, and you are free. All of you are equal in the eyes of the law, and around you are only brothers. As you know, Liberty also means duties. Be worthy of this freedom, by showing France and the world that it cannot be dissociated from order and hard work…”

And so law and order was respected until the very last, as no early abolition had been proclaimed. Despite the deep foundations of colonial society, no insurrection had occurred.

This emblematic painting created in 1849 by Albert Garreau, who was present at the ceremony on 20th December, sought to depict this perfect ‘abolition by law’: in one hand, Sarda-Garriga holds aloft the official document granting immediate freedom to all slaves, and in the other hand he points to the tools of the trade, emphasising that this new freedom was not synonymous with idleness. In front of him stand the newly Freedmen, men and women prostrating themselves as a sign of recognition and acceptance of this republican decree from Paris. Thus, in Reunion Island, the provisional government’s wish for a legal transition as announced during the Parisian Revolution of February had been strictly respected. Here, the abolition was indeed ‘granted’, and not the result of an armed uprising. Unlike the format so lauded in the West Indies, the Indian Ocean had opted for a different path.