“I have given Léocadie to Mélanie” .

These words, written by Ombline Desbassayns in 1807, summarise the relations between these two women, sharing a common family history, but with parallel destinies that were never shared.

After writing these words, Ombline never mentioned Léocadie again.

Two women, but each with a totally opposed status: one a slave, the other a slave-owner, and despite apparently similar itineraries, two totally different lives. The first possessed not only a huge property, but also slaves, whose destinies she largely held between her hands. The other owned nothing, not even her children.

The two women were also daughters, wives, mothers, and grandmothers.

Léocadie was born in 1757, of Pierre and Pauline, slaves belonging to Henry Paulin Panon-Desbassayns and descendants of Dominique Modoze and Pierre Mobiliha, two Indians married in 1690 .

Their patronymic was only handed down to the second generation, before the colonial powers decided to do away with patronymics, thus denying the slaves’ ancestry and their identity.

Léocadie, like her nine brothers and sisters, was breastfed by her mother .

While Ombline’s close family became reduced after the death of her father in 1801 , Léocadie’s family presented certain specific characteristics.

This large family preferred to set up alliances with Creole slaves and a very large number of its members were domestic slaves: maids, nannies, foremen, head waiters etc. .

In this respect, the family was rather different from the majority of the victims of the slave trade coming from Africa and Madagascar, whose unions we very often have little information about, but who had just as many descendants.

The nature of the relations between these two women who “cohabitated” for over four decades, each in her specific field and above all dependent on her status and each playing her role, is a fundamental question.

We do not suggest any ‘connivance’ between these two persons, and their both being women produced no complicity between them.

Their interests, undoubtedly essentially emotional, only bear a resemblance regarding their children, notably feeding and taking care of them.

Ombline was born in 1755, of Julien Gonneau and Elisabeth Léger; the latter died in childbirth, leaving Ombline an orphan on her mother’s side and an only child; she was thus fed by a wet-nurse, Madeleine, a Creole (1735-1814):

“Mother’s wet-nurse has died too” .

The question of wet-nurses and breastfeeding is a thread determining the relations between the two women. Léocadie, but also her sisters, sisters-in-law, daughters and granddaughters, became wet-nurses for Ombline’s children and some of her grandchildren.

Julien and Philippe Desbassayns were apparently nursed either by Appoline, Léocadie’s mother, or by Darie, Léocadie’s sister, by Clotilde or Dorothée, the other sisters. As for Euphrasie and/or Joseph Desbassayns, they were certainly nursed by Perpétue, who travelled with them to France between 1790 and 1793. Finally, Charles was nursed by Toinette, Léocadie’s sister-in-law. The accounts of these different nurses left by Ombline’s children reflect a certain attachment to them.

Following the birth of her daughter Candide in 1780, Léocadie was wet-nurse for Mélanie, born in 1781. She was the one who travelled to France with Ombline’s daughter and the whole family was greatly affected when Léocadie died in a village close to Toulouse.

We can also put forward the hypothesis of a close emotional link between Léocadie and Mélanie; the role of wet-nurse implies close contact, notably physical, between the nurse and the child. Any difference of status, sex or colour is of little relevance when it comes to this relationship.

This question was so important that Joseph de Villèle, Ombline’s son-in-law, mentions the subject of breastfeeding and wetnurses several times.

Representations linked to breastfeeding in the society of the period vary. While Joseph de Villèle was raised by a nurse ten kilometres or so away from his parents on Bourbon island, most wet-nurses worked in the home. His account of the advantages and drawbacks of using nurses is interesting. He was still living on Bourbon when he wrote:

my wife, who feeds her baby … as her breasts are sick, each time she suffers from terrible pain… Mélanie feeds her little Louise and she is absolutely fine. The child is also quite happy to be fed from a bottle … Here we have no other way than for her to be fed with precision and for over one month and for this we have a little dog just seven or eight days old and here a number of children have been fed in this way.

This reference to using animals on Bourbon, to solve the problem of cracks and accumulation of milk in breasts following a birth apparently only concerned women who were free citizens. It could have concerned Ombline, following the birth of non-viable children.

While Joseph de Villèle had a negative opinion of using Creole nurses, his brother Jean Baptiste, married to Gertrude, another of Ombline’s daughters, wrote:

“My little boy was not getting enough nourishment, and in these circumstances almost died. We were forced to find him a nurse, whom he accepted very well, and who has been feeding him extremely well to this day.”

His wife Gertrude wrote:

“The Blacks are sensitive to what the children do for them. Frédéric particularly has a nurse whom he is very fond of, and who was glad to feed him. He was close to death when this woman began feeding him.”

When feeding Ombline’s children, the nurses shared their milk or neglected to feed of their own children. There is nothing to say that they were feeding two young children at the same time. By setting up this close link implied by breastfeeding, meaning that at times the survival of the child was dependent on their availability, these women, related to Léocadie, naturally appropriated one ‘part’ of these children. However, this did not create a link between the wet-nurses and Ombline, who was thus deprived of one aspect of her role as mother. We do not know why she made use of slaves as wet-nurses on several occasions; it may have been a late-18th-century social tendency which questioned breastfeeding, or maybe physiological impossibility. However, she did not share the same attitude as her son-in-law Joseph de Villèle for whom:

“Not once did she [his wife] consider making use of a wet-nurse and I will refrain from suggesting it to her. In this country, the consequences are very often detrimental.”

This was certainly because on Bourbon, nurses were Black slaves, while in Toulouse they were free citizens and white, which led to his making use of the services of a nurse for one of his children born in that region.

The power held by women slaves over their slave-owning masters can also be seen in other colonial regions and countries, such as Brazil, the Caribbean islands or North America. Very often, white babies being fed by black women came up against prejudice concerning colour and risks for the newborn baby of catching diseases, but also forms of ‘degeneration’ linked to the status and colour of these women.

The descendants of these two dynasties thus share a comment element: the history of breastfeeding by a black woman slave.

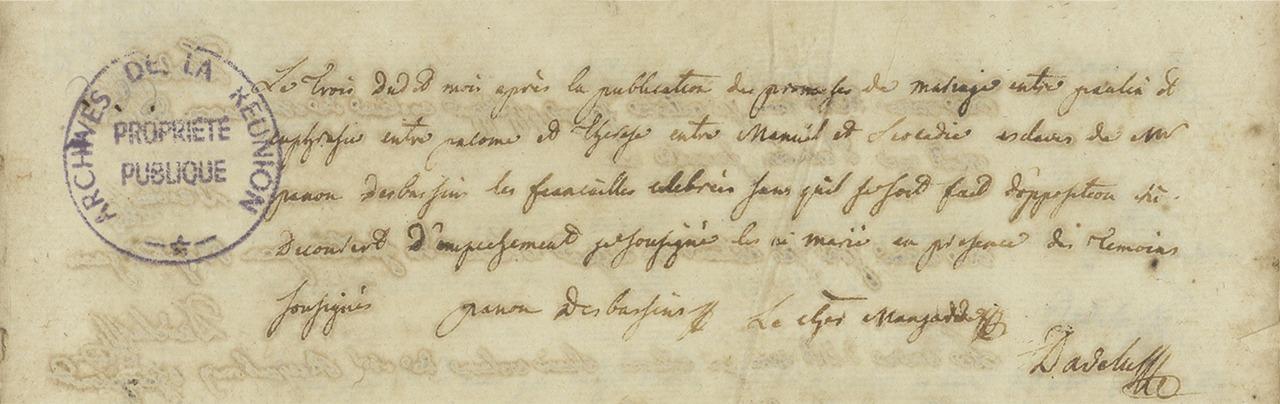

While Ombline married Henry Paulin Panon-Desbassayns, 20 years older than her, before she turned 15, Léocadie married Manuel , an Indian slave the same age as her, when she was over 19, thus renewing, in a certain manner, with her “stolen” (unrecognised) ancestry.

Between 1777 and 1801, Léocadie had nine children, eight of whom lived to be adults. Her first child was born when she was 20, while Ombline gave birth to her first son when she was 16.

Between 1771 and 1797, she had 14 children, five of whom died at birth or at an early age. Infant mortality during this period concerned both children born of the free population, and those born of slaves.

The family history of each of the two mothers is somewhat different.

Léocadie’s children became distant from their mother following the death of Henri Paulin Desbassayns, then Léocadie leaving for France in 1807. Until that date, they lived with both of their parents.

“Julien belongs to Henry, mother gave him to her and Petit Pierre belongs to Frédérick (De Villèle). I’m giving you this information and my sister Mélanie will be happy to get to know them. Charles is very pleased with Julien.” (Julien and Petit Pierre were Léocadie’s two youngest sons).

Following the inheritance, some of them went to Saint-Denis, others to Saint-Leu or Sainte-Marie. This dispersal explains why the brothers and sisters, as well as the children, were given different patronymics when slavery was abolished.

We can note that Julien, Léocadie’s youngest child, born on 22nd March 1801, was six years old when he was separated from his mother, which was an infringement of the law forbidding separations before the child was seven .

At a very young age, Ombline’s children were sent to France to study. While they saw their father during these stays, some of them spent many years without seeing their mother.

While all of Léocadie’s children remained on Bourbon, several of Ombline’s children settled in France for good, which was the case of three of her sons and one daughter, Mélanie.

Both of the mothers were regularly separated from their children, but during different periods in their lives and for different reasons.

The situation as grandmothers was also different. While Ombline only had occasional contact with several of her children, it appears that she more regularly took care of her grandchildren, at least those living on the island. Léocadie, on the other hand, no longer living on the island, only knew of the birth of two of her grandchildren, and did not see the others grow up.

When she organised her voyage to France, Ombline knew very well what she was doing and how to make use of her slave Léocadie.

With the exception of one short stay in Mauritius, Ombline spent all her life on Bourbon island. She died on. 4th February 1846, aged over 90. Following her funeral, which was an important event for the colony, her tomb, as well as a statue raised to represent her, became part of the landscape on Reunion.

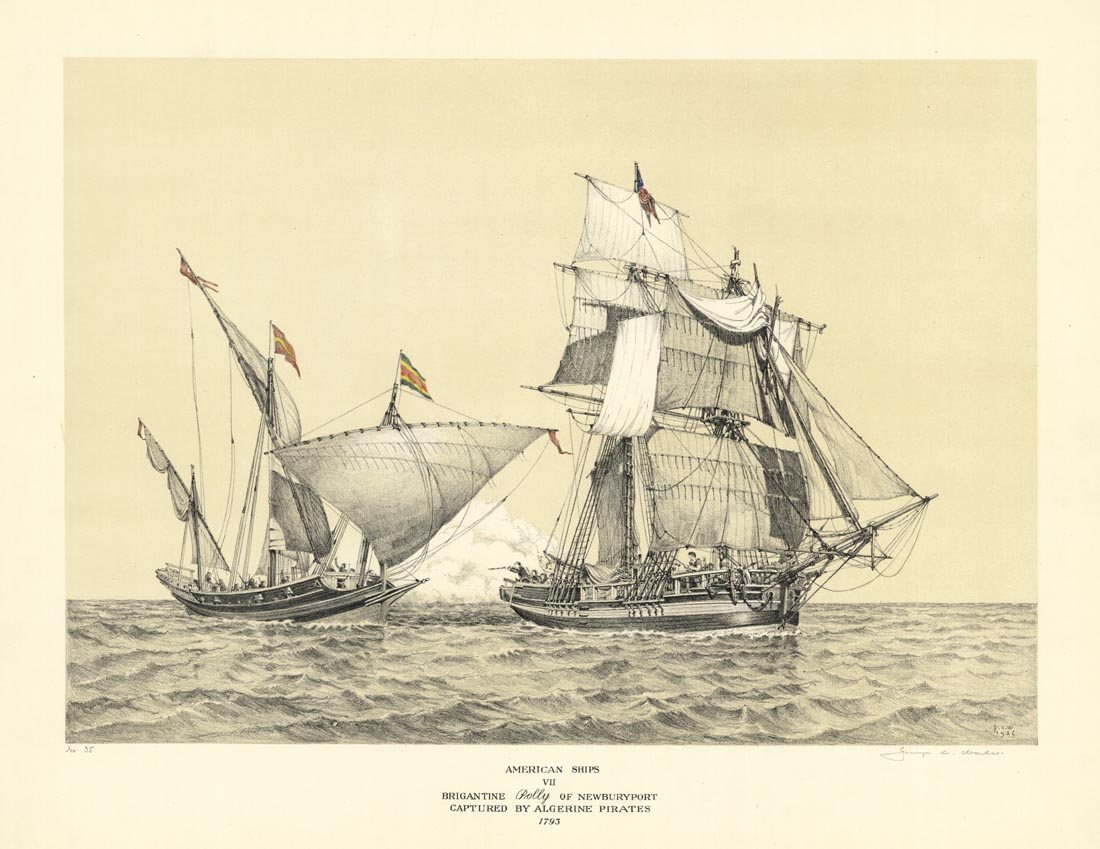

When Ombline sent Léocadie to France to accompany Mélanie, her experience was one of exile and uprooting. The voyage is described in detail by Joseph de Villèle . Due to the war between the French and the British, le Polly, the ship on which they were travelling, stopped off in New York and we have precise information concerning life on board. For example, he describes crossing the Equator:

“the ceremony of crossing the line… they (the sailors) spared our children and Cady.”. »

In New York and Broad Way, where the family stayed in a guesthouse “half price for the children and for Cadi, the black servant”, Villèle wrote:

“The blacks and the Negro women are as well-dressed as the others, the women wearing elegant hats, tulle caps and taffeta dresses, which our children found very amusing and which made Léocadie, our black maid, raise her eyes to the sky.”

She stayed there for a few weeks before leaving for Bordeaux, then Toulouse, where the De Villèle family were living, and finally Mourvilles Basses, a small village where the family had their château.

Joseph de Villèle’s father also mentions Léocadie:

“I have obtained permission for Cadi to be welcomed and I received the reply from Mr DECRES … I admit your good principles concerning the fate of this Negro servant, who nourished your wife, and looked after the children and who will be so useful to you.”

Mélanie Desbassayns thus left with Léocadie, and not with her mother.

The confined space during the long six-month voyage necessarily led to physical and social contact between these persons of totally opposite status.

The importance of the presence of Léocadie in the De Villèle château is reflected in the documents, written by the master, where he emphasises responsibilities regarding management of the family’s finances. During this period, when he was going through financial difficulties, he declared:

“The domestic staff must be closely integrated into this economy. For two years, the Negro woman who had breastfed Mme de Villèle, had supported her mistress as well as she could. However, she found the climate difficult and in October 1809, she let herself die, to the absolute despair of the entire family. ” .

On 2nd December 1809, “The Negro woman Léocadie, domestic servant … daughter of Pierre, a Black, and Pauline, a Negress,” died “of exhaustion” in that village.

We have no trace of Léocadie’s life in that place where she was exiled, no sign in the village cemetery where she was, nevertheless, buried. The tombs of the De Villèle family are, on the other hand, very much visible. She only lived to be 52.

Contrary to what she had lived through for half a century, in addition to a new geographical environment, Léocadie discovered a difficult climate and above all isolation resulting from her identity. Everybody at the De Villèle château was free and white, not just the masters, but also all the staff and the various employees on the estate, a total disruption for Léocadie and without any doubt leading her to be ill-at-ease and to her final despair.

We can wonder about the attitude to emancipation within the Desbassayns dynasty and the consequences of these for Léocadie’s family.

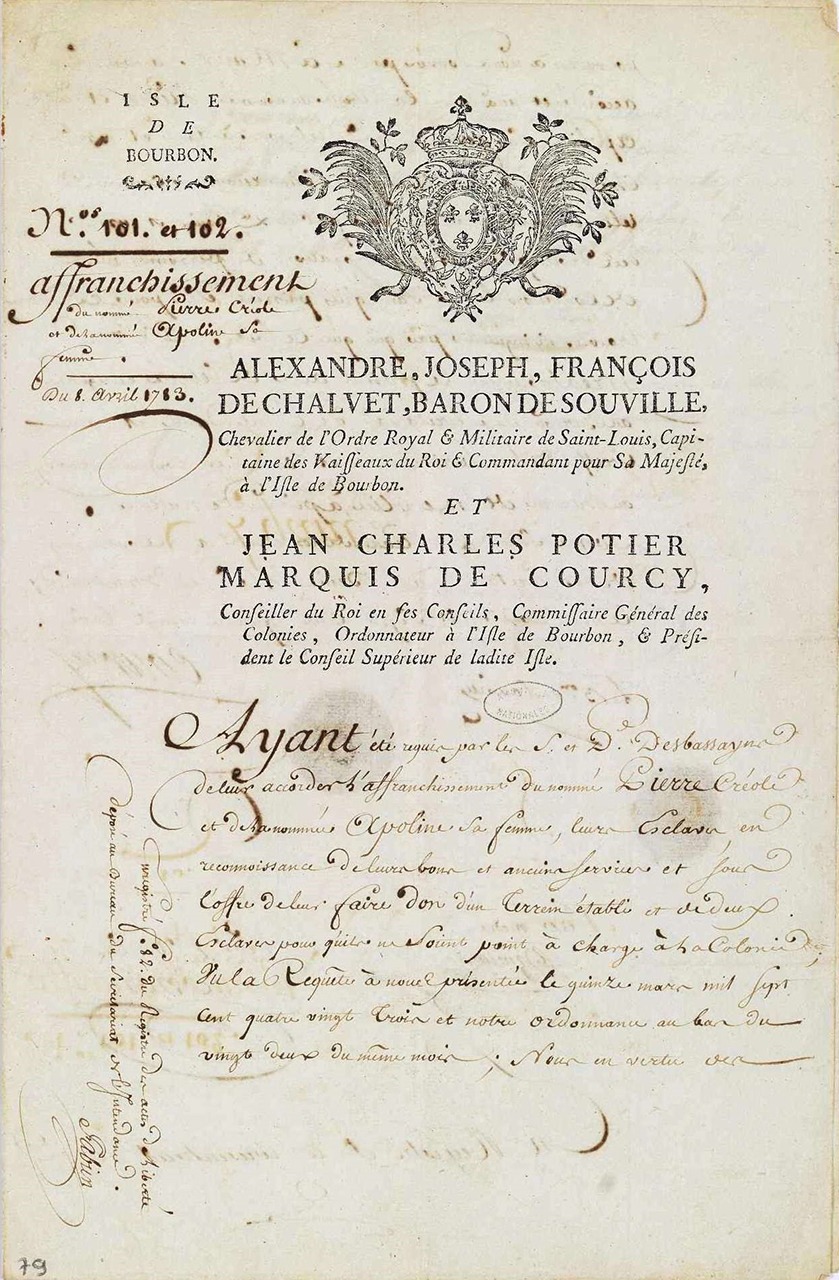

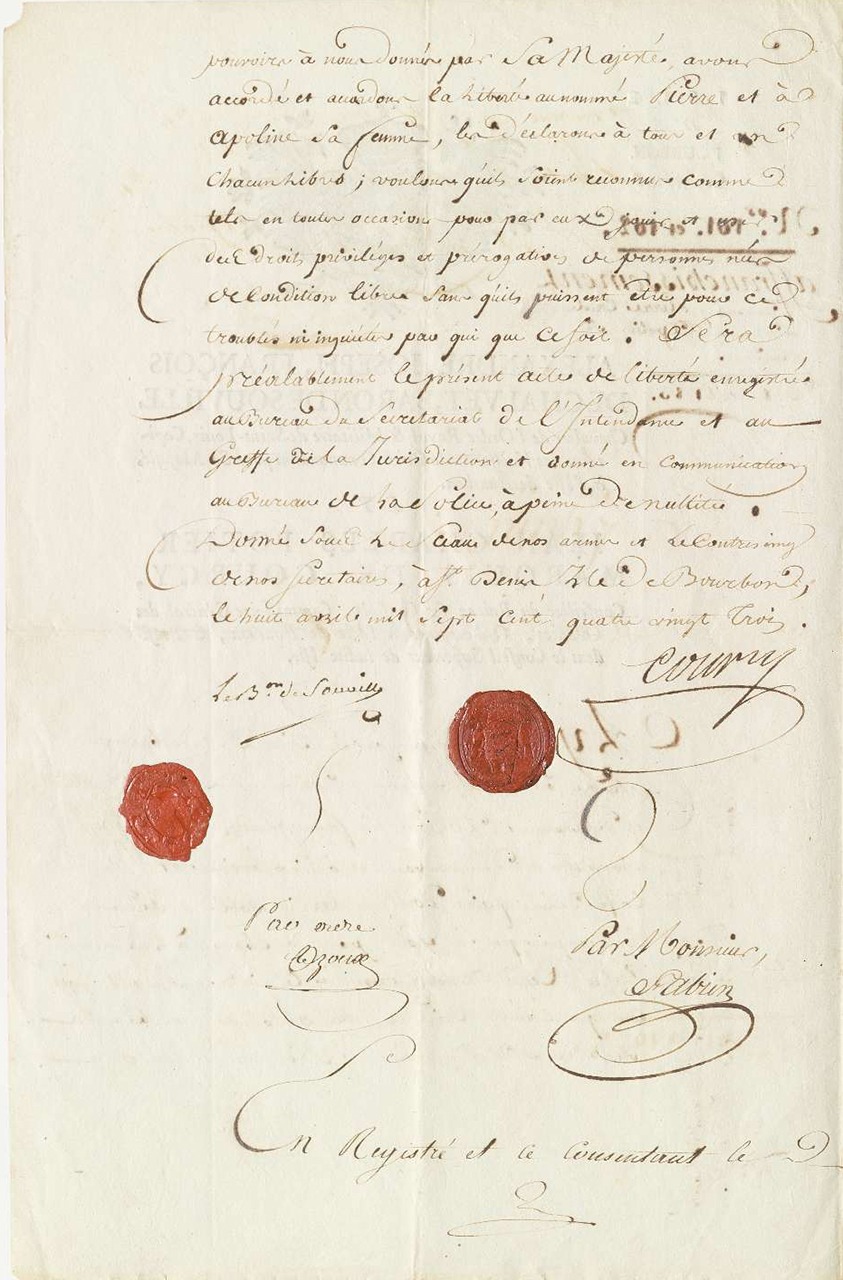

While Julien Gonneau, her father, emancipated 15 slaves in 1794 her daughter did not decide to emancipate any. Henry Paulin Desbassayns, like his father Augustin Panon, emancipated a small number of slaves, more exactly three: Léocadie’s father and mother , to whom he gave a plot of land and a few slaves when they were over 50, as well as Séverin, one of Léocadie’s nephews, who accompanied his master during his first voyage to France at the end of 1784, but who could not set foot on French soil, since the necessary formalities had not been carried out. Emancipated in 1785, he settled in Saint-André for some time and died there in 1803, bearing the name of Debassin , which he certainly initiated but which he could not hand down to his children.

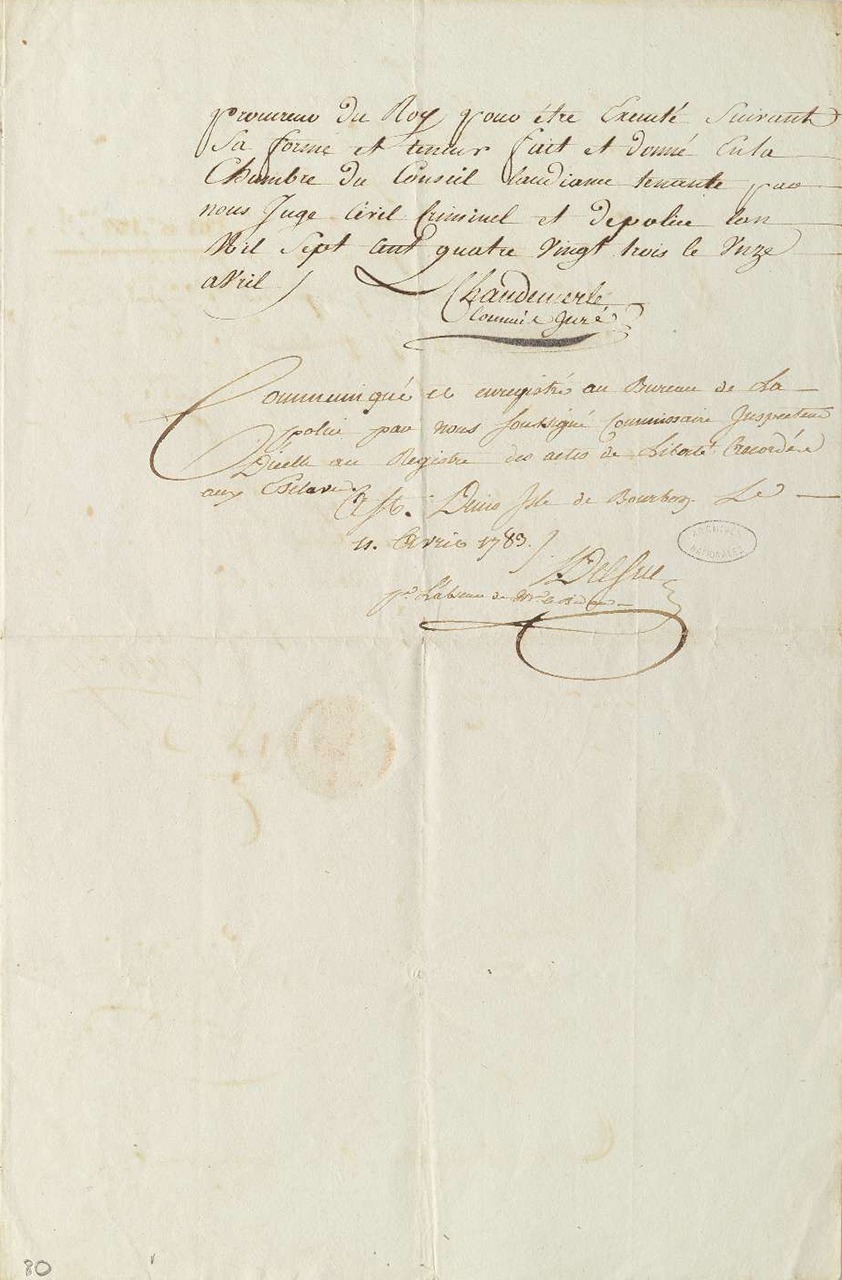

Emancipation deeds of slaves Pierre, Creole, and his wife Apoline, with ‘donation of a plot and two slaves so that they will no longer be dependent on the colony.” 8th April 1783.

Collection of French National archives. Panon-Desbassayns et de Villèle collection, inv. 696AP/4, File 3

Ombline only considered emancipation. In a ‘will’ dated 1807 , she declared that she wished her heirs to emancipate 10 or so slaves, including Manuel, Léocadie’s husband, and that she wished for Léocadie’s children to be able to choose their masters. Léocadie embarked on her voyage on 14th March of the same year. However, Ombline did not die until 40 years later and in her last will, no emancipations were mentioned.

This behaviour throws light on the nature of the relationship bringing together these two women of totally opposite status, the power of one over the other being total.

So the remarkable life stories of Léocadie and Ombline are only truly similar when it comes to the relationship the latter had with her children. Their totally opposite status, one being a slave and the other a free citizen, will always remain the basis of their ‘cohabitation’. Whereas one, Ombline, enjoyed total power over the other, Léocadie had a totally different power, symbolically greater, that of being a substitute mother.

The complete family tree of Léocadie drawn up by Christian Galas