Was there any official legislation prohibiting slaves from education? Apparently not, but this is hardly surprising: the norms of slavery were applied without objection. But on all other aspects of the question of schooling, levels of education, target groups, and teachers to be recruited, opinions were divided.

For the central government, the colony only required elementary schools for poor children. For children of the bourgeoisie, the authorities requested that, given the small class sizes, they continue their studies in France, and this at the expense of their parents. Members of the Creole bourgeoisie were firmly against this, and succeeded in making the central government back down. This resulted in the creation of a local Collège Royal providing children with primary and secondary education. For under-privileged children, whose parents were either poor white colonists or freedmen of colour, two Congregations were contacted: that of the Brothers of the Christian Schools (for boys) and that of the Sisters of Saint-Joseph de Cluny (for girls). The powerful Desbassayns family played a major role in the setting up and running of these establishments. They invested all their resources and interpersonal skills to ensure that this school system got off to a good start. Thanks to this, the Collège Royal benefitted from elite teachers from the prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure and Ecole Polytechnique, convincing both churches to recruit them quickly in order to open the colony’s much-awaited schools as soon as possible.

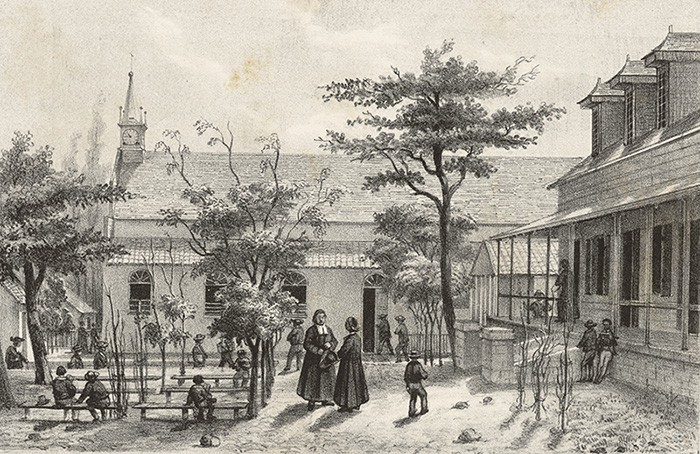

There were two distinct approaches within the school organisation set up in Bourbon, managed separately for different clienteles. They each had specific objectives, but both adhered to one key obsession: to ensure the continuation of slavery and colonial rule. On one hand, there was the Collège Royal with its clear culture of excellence, with classes running from primary to baccalaureate in order to train the colony’s future ruling elite. Under the watchful eye of local dignitaries, the school’s goal was clear: to inculcate a firm colonial mind-set for these young people who had been born with a privileged social and racial status. On the other hand, there was the free education provided to under-privileged children (of both white settlers and Freedmen of colour) dispensed by the two Congregations: the Lasallian Brothers and the Sisters of Saint Joseph de Cluny. The teaching that these Congregations were supposed to provide to this social group was intentionally basic, with added emphasis placed on moral and practical aspects to ensure submission to the colonial order and its system of slavery. The objective was to provide useful and moral education with principles which were expected by colonial society for this type of school system whose development we shall now examine in greater detail.

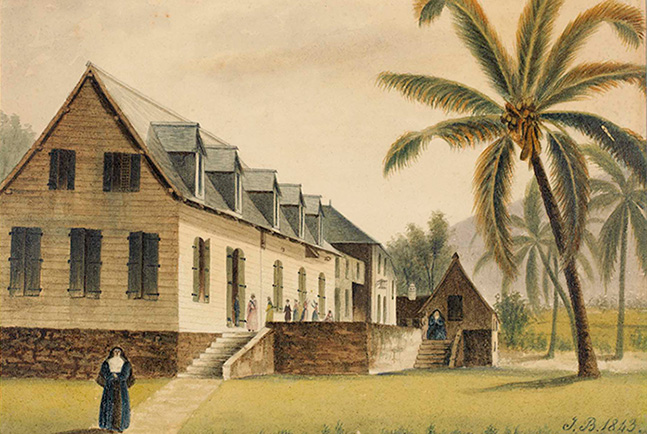

In 1817, the Brothers of the Christian Schools were the first to get to work. Six of them arrived in Bourbon on 15th May 1817 and opened three establishments in the process: one in Saint-Denis, a second in Saint-Paul and a third in Saint-Pierre. In the weeks that followed, four Sisters of the Congregation of Saint Joseph de Cluny also landed in the colony. They settled on the property of Madame Desbassayns in Saint-Paul, opening their first establishment on September 8th, 1817.

The next day, a second group of Sisters arrived in the Colony. They settled in Saint-Denis and opened their school on 2nd January 1818. Opening and developing of congregational schools did not come without difficulties. These schools were of different types and were introduced during two distinct periods.

The first period ran from the establishment of Congregations (1817) up to the July Monarchy (1830), and was marked by the normal difficulties arising for any new school (Bourbon was no exception, as premises or accommodation were unavailable and openings were delayed), but also by the nature of colonial society and its organisation. Two specific conflicts were particularly significant. The first took place in the classroom: the limited school places on offer in the colony and the fact that this schooling was free led to a racial mix in the first schools set up by the Brothers and Sisters. Because of the complexity of colonial society, the same classrooms were used by both whites (not only the impoverished) and Freedmen of colour. This social and racial cohabitation did not go smoothly.

However, these racial issues were not the only concerns of the slave-owning society. There was also a certain education to be given, which had to be in accordance with the ruling order. But the education put in place by the Brothers and Sisters was based on emulation, as these Congregational schools wished to promote a format based on merit, known as the Monitorial system. While limited, upward mobility would thus be possible at school, but this was considered totally subversive by colonial society. Both Congregations were called to order, and then requested to create separate spaces for different racial groups, and the Monitorial System was banished from the colony.

The second conflict pitted the colonial authorities against the higher authorities of the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Joseph de Cluny. It all began in 1821 when, following the death of the head of the community in Bourbon, Governor Freycinet pushed to select and appoint his own replacement. This coup de force went against all the Congregation’s prerogatives, and was denounced by its founder, Anne-Marie Javouhey, who finally won the case in the supreme court. She regained her authority among the Bourbon community and entrusted its leadership to her own sister, Rosalie Javouhey.

In 1830 there was only one school left in the Colony, that in Saint-Denis, which had 183 pupils. As for the Sisters, they were able to keep their three establishments which had 114 paying pupils, 97 in the free classes reserved for poor white girls and 132 in those reserved for girls of colour.

The second period, which began with the July Monarchy and ended with the advent of the Second Republic, was marked by very profound upheavals that ended with the abolition of slavery. It was in this context that the measures taken for educating slaves, the very last social group of Bourbon society, appeared with a rhythm and gravity that clearly reflected the nature of a colonial society deeply affected by the transition of French society towards capitalist production.

In fact, after having contributed considerably to the economic development of European cities, the system of slavery ended up becoming a hindrance. First tackled by Adam Smith at the end of the 18th century, criticism of this system became firmly established in France, its leaders agreeing with the arguments of liberal economists. It was in this context that the law of 4th March 1831 was passed, putting an end to the French Slave Trade, followed by the creation in 1834 of the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery. These key abolitionist leaders such as Tocqueville, Passy, or de Broglie published numerous reports demonstrating the impossibility of maintaining slavery and various measures were then taken by the central authorities to reform the system. But these measures, although reformist, provoked hostility from both the slave-owners and the colonial administration, as illustrated by their conduct in the face of the provisions of these laws concerning education.

These laws did include a considerable educational component, which was a radical novelty for the time. In order to understand this, it should be remembered that slaves had never received any education previously. Religious instruction itself was met with hostility from the colonists. In 1839, a fund was set up for the religious and basic education of slave children, but this was not implemented in the colony due to the reticence of Governor Hell, who declared to the authorities that “the time when it will become possible to provide blacks with basic education is still far away”.

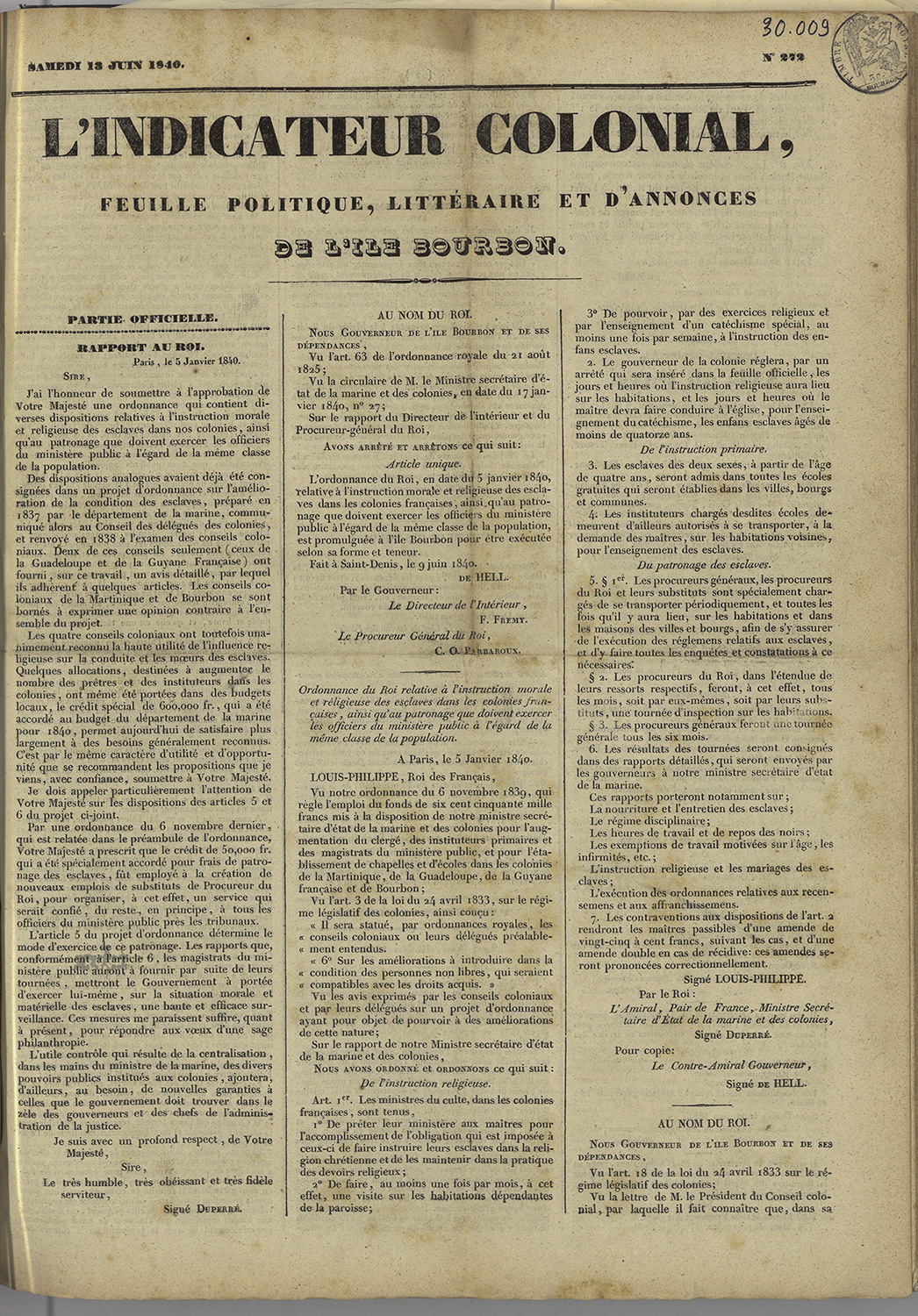

In 1840, a royal decree clearly raised the question of the education of slaves, but its reception in Bourbon was quite telling. The first two articles of this decree were devoted to religious education, providing for monthly sessions of religious instruction in homes and weekly catechism classes for slave children in parish churches. The next two articles dealt with basic education, stipulating that “slaves of both gender over the age of 4 would be admitted to all free schools established in the communes,” a measure initially envisaged as compulsory by the government and then made optional in the face of an outcry from Colonial Councils (including that of Bourbon). But this measure, even in a diluted form (compared to the initial draft), was still unacceptable to the colonists, who were all the more determined to oppose it because, among the colony’s administrators, they were able to find willing collaborators, despite calls to order coming from the central government. Despite the fact that it was his job to enforce the decree, Governor Bazoche (Hell’s successor) wrote to the Minister of the Colonies saying that it would be untimely, inappropriate, costly and dangerous for the Colony, conceding that only “a few lessons of basic morality” could be envisaged. The colonists could hardly have wished for a better champion to their cause. Thus, when the Minister of the Colonies was questioned about the application of this decree and the use of the funds to implement it, he was obliged to acknowledge its complete failure, especially in Bourbon. In 1845, there were no slave children attending school in the colony. The funds had in fact been embezzled, and any application of the decree sabotaged by colonists benefitting from zealous support from the local authorities, governors and magistrates, in spite of calls to order from the government. Victor Schœlcher and his friends were disgusted by this outcome.

A new decree was issued on 18th May 1846, this time stipulating that the education of slave children was now mandatory. According to official instructions, the objective was to create an extremely basic curriculum which “aimed to reconcile the accomplishment of scholastic education with the fulfilment of [young slaves’] duties in the home”, boasting a philosophy which sought to moralize and domesticate, instead of actually to educate, emphasizing above all the importance of hard work. But despite the binding nature of the decree and its clearly stated limits, the law was barely implemented in Bourbon, as the colonial administration and society continued to band together to sabotage its application, as revealed by the ‘Monnet affair’.

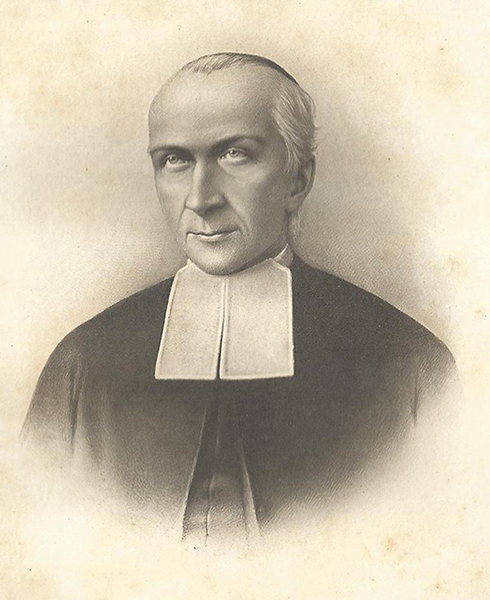

Arriving in Bourbon in June 1840, Abbé Monnet devoted himself to the religious education of slaves, laying the foundations for a new pastoral movement known as the ‘Mission des Noirs’. Working in line with government policy, Monnet met with hostility from the majority of the colonists, with the exception of the powerful Desbassayns family whose leading influence in French colonial history gave him confidence and support. While staying in Europe in 1846, Abbé Monnet was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour by the French government and, in Rome his work earned him a visit from Pope Pius IX, who appointed him Apostolic Vice-Prefect of Bourbon. However, upon his return to Bourbon on 12th September 1847, Monnet was greeted by hostile demonstrators who accused him of “being at the heart of Catholic opposition to slavery”, before being expelled by Governor Graëb just a fortnight later, “in the Colony’s best interests”.

This alliance between the colony’s administrators and the settlers was constant, likened to a ‘steel network’ by Victor Schœlcher, and reveals how impossible it was to bring about any reforms within the slavery system. On the eve of Abolition, the colony had seven schools run by the Brothers’, four of which took in a total of 232 slave children. Among these establishments, there was one in Saint-Leu, whose director was Brother Scubilion. As for the Sisters of Saint-Joseph de Cluny, only three establishments took in slave children, numbering 380.