Following the abolition of slavery (20th December 1848), the Colony developed the system of indentured labour, bringing in workers from Africa and its neighbouring islands (Madagascar, Comoros), India and Asia in general. Once settled in colony and their contractual obligations fulfilled, these indentured labourers could, depending on their means, become landowners, be integrated professionally and, together with the other members of the population (whites and descendants of slaves) contribute to forming the population of Reunion as we know it today. Today, the island’s population faces a high rate of unemployment: 18.43% compared to 7.1% in mainland France (INSEE, 2023).

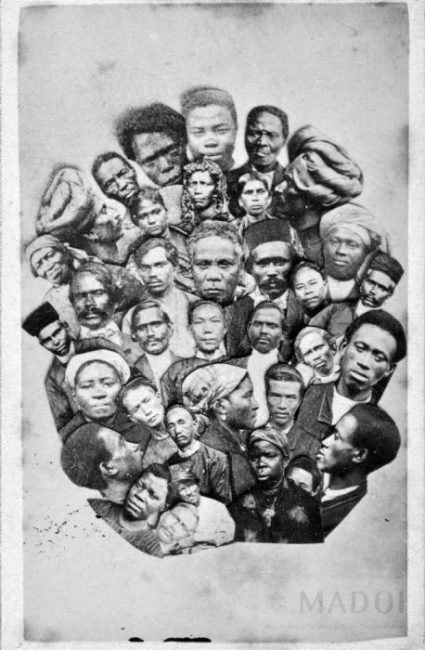

Collection of Indian Ocean museum of decorative arts. inv. 18P1.7_PHO.2012.2274.07a

This has probably had a negative effect on their relationship with their own history and culture, mainly handed down orally, and it has altered the relationship with the notion of their ancestry, leading them more and more to question their identity.

The notion of otherness necessarily occurs through recognition of oneself by those around us: however, in a postcolonial context, it may be complicated if one can only function through closing in on oneself regarding one’s identity, thus reflecting a breach in the construction of this identity.

Many of the authors quoted here consider that this construction is the result of a denial of the other, creating a society in search of its origins: “we can note a development of the African identity, of identity standards of the Malagasy culture, and for certain Reunionese having Indian ancestors, this goes hand-in-hand with a rejection of the term Malabar, with a preference for that of Tamil or Hindu, these last two, they consider, referring to a more prestigious civilisation […]. These claims, originating in the family or simply the society and not polluted by external contributions, […] give rise to unhealthy attitudes tainted with ethnocentricity.” (Pourchez, 2005, p. 11).

According to local history, the migrants and those deported sometimes had to practice their original religious rites in secret, these being officially replaced by the dominant Christian religion. Today, several beliefs are practiced in a single household.

Reunion thus suffered from several symbolic wounds: slavery, indentured labour, often with no possibility of return, and the socio-economic collapse of the situation of the settlers. To this can be added the negation of identity through prohibition of the original language, then of Creole (forbidden until the 1970s) and the virtual absence of island’s history in school curriculums.

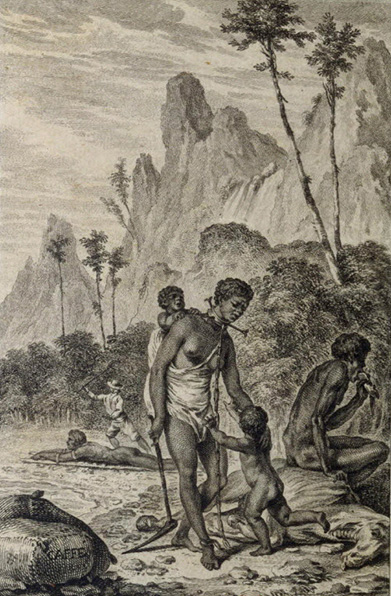

During the colonial period, the children of slaves “did not belong” initially to their parents, being first of all the property of the master, then of the mother . In this social environment, the father was stripped of his role of parent and of his filiation. Actually, these migrants did not all originate in matriarchal cultures: depending on his origins, the father could have a role to play in the children’s education. In postcolonial African societies “it was the father who taught the boy his function of being a man” (Camille. F., 2008), whereas during colonisation, the education of “the child” was the woman’s job (matri-focality) and the function was taught essentially by the State schools.

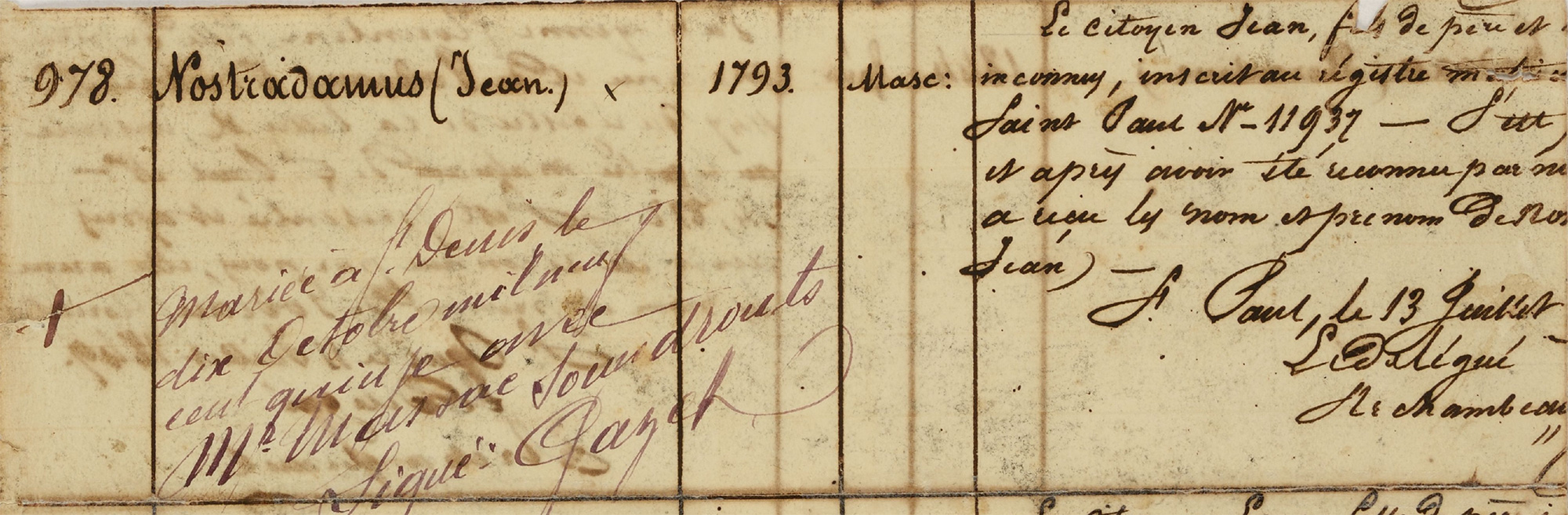

For the psychologist J.-P. Cambefort (2001, p. 64), the destruction of the paternal conjugal-educational role blocks the child in his emotional attachment, virtually exclusively turned towards the mother, which has a negative effect on the child’s socialisation, his perception of social limits and therefore of the law. Cambefort notes that for thousands of families, the fact of taking on a patronymic of nicknames to stigmatise the descendants of emancipated slaves (Nabuchodonosor, Tantale, Hamilcar…) (ibid., p.134), was harmful to be function of father. The psychologist Bianca Benvenuti also asserts that the factors of psychological breach in filial bonds are harmful to thought and to relationships (all the more so) when parental transmission is biased throughout the entire society or entirely destroyed by collective traumas (op. cit, p. 216): the latter can then have a negative influence on the quality of the relations between the child and his parent.

Indeed, the slave did not know whether or not he would have a future (the master having the power of life or death). This philosophy of the “present moment” is frequently expressed through hyper consumerism and excessive debts, encouraged by an idealisation of Western sociological and cultural standards, particularly consumerism. This influences the section of the population that is dependent on social benefits, ‘encouraging’ them to buy manufactured goods beyond their financial capacities: a clumsy attempt at shining socially, at being equal to the better-off social classes.

In addition, however, in the context of the absence of the right to self-expression in the colony (associated with cultures not fundamentally focusing on considerations of absence of endogenous psychological well-being ) and due to the fact that for years the woman’s role was limited to household tasks and the education of children , we can here find the reasons behind the huge number of cases of domestic violence. The biggest paradox remains that the “super-fathers”: the elected members of the Republic, often involved in corruption, hold the power in a climate of tension when faced with the task of distributing contracts based on electoral requirements. They are models of negative identification (“if the Mayor can do it, I can do it). The irony is that the descendant of the slave in his turn takes on the role of master, giving himself the right to carry out all-powerful actions, without the laws of men being respected, despite these being a guarantee of equity.

The image that the child has of the father is therefore not particularly positive: in a study carried out in 1990 based on 1808 professional high school pupils aged between 17 and 25, both girls and boys, Cambefort (ibid., p. 99) demonstrated that the majority (80,5 %) of the pupils had a negative image of their father or stepfather, taking no interest in their education, with a total absence of dialogue, very often demonstrating physical violence, the pupil being ashamed of him. He was authoritarian, sometimes alcoholic or described as being crazy.

This study should be seen in its context, since it was carried out in professional high schools: these pupils often come from precarious family backgrounds. This would explain, at least partly, the high level of criticism regarding the fathers, which would not necessarily be the case in a general high school. These adolescents, expressing opposition to authority virtually systematically in their age-group, may also be exaggerating the perception they have of their situation and therefore their responses to the questions. The figures do, however, emphasise the family tensions existing. 1.7% of the pupils noted that the father or stepfather had attempted to murder their mother; this does represent 30.7 children out of 1808, the equivalent of a whole class of pupils.

Beyond the use of “peach whip” (branch of the peach-tree), the child can be punished by being forced to kneel on sea salt (to purify the soul). Applying violence is fast, simple and bears no opposition: “often on the pretext of educational principles” (op. cit.), the argument being that what used to work well in the past can work well today, a fact that can be linked to punishments meted out during the colonial period on Bourbon: according to the historian Yale Néba (2009, p. 28), “slaves did not have the right to defend themselves against the aggression of their masters… Their punishment was death”. Also, according to the Black Code, “a simple glance, a word, an accidental gesture, a mistake, an accident or weakness were all reasons for a slave being whipped (idem., p. 31)”. But if we consider the destruction of symbolic paternal laws, these coexist with the all-powerful role of the mother.

Clinical psychologists regularly note that the child sleeps in the same room or even the same bed as the parents, sometimes even up to adolescence . Dummies and nappies are conserved up to the age of four or five and mothers breastfeed up to the age of six: a cultural heritage of certain African communities where the child can quench his thirst at any available breast. But beyond cultural considerations, this behaviour is maintained for psychological reasons: sharing the bed with the child makes it possible to avoid conjugal sexuality and retains the child in a state of psychological dependency on the mother (and vice versa). The father, himself raised in a context of the preponderant position of the mother, is thus limited in claiming his conjugal role, his role being restricted to that of mere progenitor and not necessarily taking on that of raising the children. His wife also reproduces her own experience: the children become property of “the mothers” (mother, grandmothers, sisters-in-law). “Traditionally, she [the mother] alone is responsible for the children’s education, the father occupying a virtually non-existent role when it comes to domestic and family tasks.” (Breton, 2005, p. 135).

The anthropologist Laurence Pourchez explains that certain fathers are discouraged during the birth: “during the design of maternity wards, with the pattern of traditional birth being disrupted […], they are excluded from the birth as were the fathers from mainland France in the mid-century, for reasons of hygiene, and reduced to smoking cigarette after cigarette in the corridor” (2000, p. 31). Consequently, there is a high rate of “illegitimate” paternity and non-recognition of children by the father: “among births referred to as illegitimate (unmarried couples and those having signed a social contract), there are also births occurring in stable couples and those by single mothers […]. In 1999, 45% of illegitimate children were recognised both by the mother and the father and 39% by just one parent”, most commonly the mother (Breton, 2007, p. 188).

Private collection of Jean-François Hibon de Frohen (1947- ), inv. 15P1.AN4.22a

“Present without being present”, the father cannot progressively distance the child from his mother. When is the mother “idolises her child, over-estimates and over-considers him […] the child no longer dares to create a distance and face up to the world, being afraid of falling from his pedestal”, according to the psychologist Jacques Robion (2003, p. 65-67). Consequently, “whatever happens, the man remains his mother’s son, owing her respect and obedience” (Cambefort, op. cit., p.94). While the father is absent, in reality, in the imagination and symbolically, it is no longer a question of being two instead of three, but of continuing to be just one “this is constructed when the child attempts to break the contract which stifles his becoming autonomous” (ibid., p. 65-67) – not permitting the son, who has become a husband and father, to invest in his own wife and children.

As a result, “the son retains of the father of the image of an eternal rival […] very often actually reinforced by acts of violence perpetrated by the fallen father, taking refuge in alcohol and becoming an outsider” (loc.cit.). This continuing fusion with the mother (as well as the influence of religion) contributes to a certain ignorance of love and pleasure: “sexuality, never mentioned [and so never turned towards the other], will be directly experienced in the act, in action” (ibid., p. 101-102). Consequently, within the family circle or close relations, sexual abuse of minors, to the level of 200 cases per year, appear to be symptoms proportionately higher than the approximate number occurring in mainland France (op. cit., p. 105).

The colonial period disrupted the role of the father in Reunion, lost between so-called traditional and modern injunctions concerning conjugal and family attitudes and functions. For a certain number of Reunionese men, there is genuine suffering regarding the role of father through the very loss of identity and parentage, leading to certain confusion, transmitted from generation to generation, as though the man was entrusted with an educational role, but without always knowing how to apply it and how to act. It seems appropriate to support them in their quest for finding their place and role within the family, by training high-quality professionals (counsellors, social workers, magistrates and police), too many of whom are also prisoners of their own distorted vision: ten or so years ago was created a hospital department labelled “women-mothers-children” (obstetrics, maternity, paediatrics), through its very title excluding the (future) father.

History should not repeat itself and in conclusion, we can quote from the psychoanalyst Lebrun: Learning to think consists in “learning, but above all learning to learn […]. Stepping away from the support obtained through learning from the other… To achieve this aim, it is essential to encounter a supporting element giving authorisation to leave the first (the mother): this is … the father.” (2007, p. 29).