As the colony developed and its population grew in number, Bourbon island had to adapt to its constantly evolving context. Several institutions were progressively set up, notably those aimed at administration of the colony, its organisation and local management.

After the French Crown took possession of the colony in the mid-17th century, its destiny was immediately entrusted to the French East India Company, a true private structure having as its priority economic profit, and which administered Bourbon directly by authorisation of the king. The colony was first run by a governor (a member of the military), assisted by a provincial council initially coming under that of Pondicherry, a French stronghold in the Indian Ocean. This embryonic organisation was gradually replaced by a more imposing structure, notably after the Île de France (currently Mauritius) was taken possession of at the very end of the reign of Louis XIV. They Provincial Council of Bourbon was replaced by a Higher Council independent of the one in Pondicherry and having the competence to govern the Île de France.

In the 1730s, Labourdonnais, governor of the Mascareignes islands, decided to transfer the centre of power in Bourbon to the sister island, where the town of Port-Louis was founded, a more welcoming harbour for his fleet of vessels. This situation continued until the collapse of the French East India Company and the retrocession of the two islands to the French crown. The structure remained fairly similar, with the exception that direct authority was now exercised by the French Secretary of State for the Navy.

Collection of Léon Dierx art gallery

Since 1789, the colony had been under the authority of mainland France, where the constitution had been amended half a dozen times. Its interior regime itself was constantly changing, due to injunctions from Paris, but also to endogenous factors.

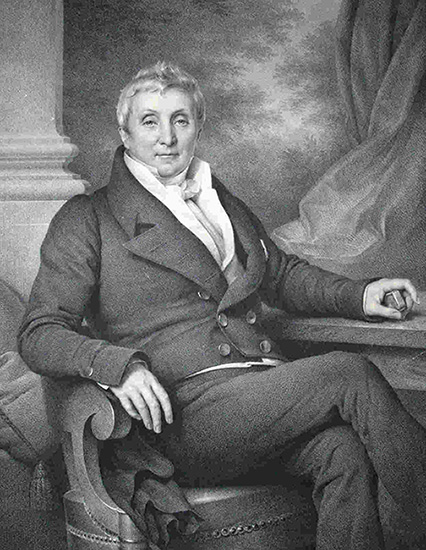

The French Restauration brought back the structure that had been applied during the Ancien Régime (with the exception that it no longer came under the tutorship of Mauritius), since Louis XVIII reorganised the French colonies on the basis of the old model: the double authority of two head administrators, one military and one civil. The former, General Bouvet de Lozier, a convinced royalist whose father had already distinguished himself for his military actions in the Indian Ocean, took dominance over his counterpart Marchant. The two following administrators were no more satisfactory, since this time it was the civil administrator, the Creole from Bourbon Philippe Desbassayns de Richemont, who appeared to dominate the military commander Lafitte du Courteil, the latter being isolated through the Furcy affair, a situation which precipitated the early departure of both administrators barely a year after their arrival in June 1817. Since the cooperation between French/Boubon administrators had turned out unsuccessful, Paris decided to put an end to this old structure and entrust virtually all the power to a single man: Baron Milius. Acting alone at the head of the colony, he soon came up against the apparent ill-will of the settlers, who criticised him for being too authoritarian. A Milius requested to be sent back in 1821. His successor Freycinet encountered more or less the same difficulties. Institutional issues (including the system of justice), having become chronic, now necessitated serious reforms, taken on by the French government under the auspices of Joseph de Villèle as from 1824.

At the heart of the French Restoration, Bourbon increasingly turned towards monoculture of sugar cane and industrial production of sugar (notably thanks to Charles Desbassayns), an activity the required a large labour force that was becoming more and more difficult to obtain, since the slave trade had been officially abolished in 1817.

The minister de Villèle carried out a precise examination of the situation on Bourbon island, where he had lived for 13 years (1794-1807) and where most of his in-laws lived, since his brother Jean-Baptiste had settled there after marrying Gertrude Panon Desbassayns. Also, his memoirs indicate that he was very close to his brother-in-law Philippe Desbassayns de Richemont, with whom he actually shared accommodation in Paris at 59 rue de Provence Seeing the logic of Bourbon being firmly governed and focused on economic prosperity, Villèle entrusted the organisation of the reforms to his brother-in-law, former authorising officer of Bourbon, Member of Parliament representing the department of la Meuse and member of the Admiralty Council, but also the State Council.

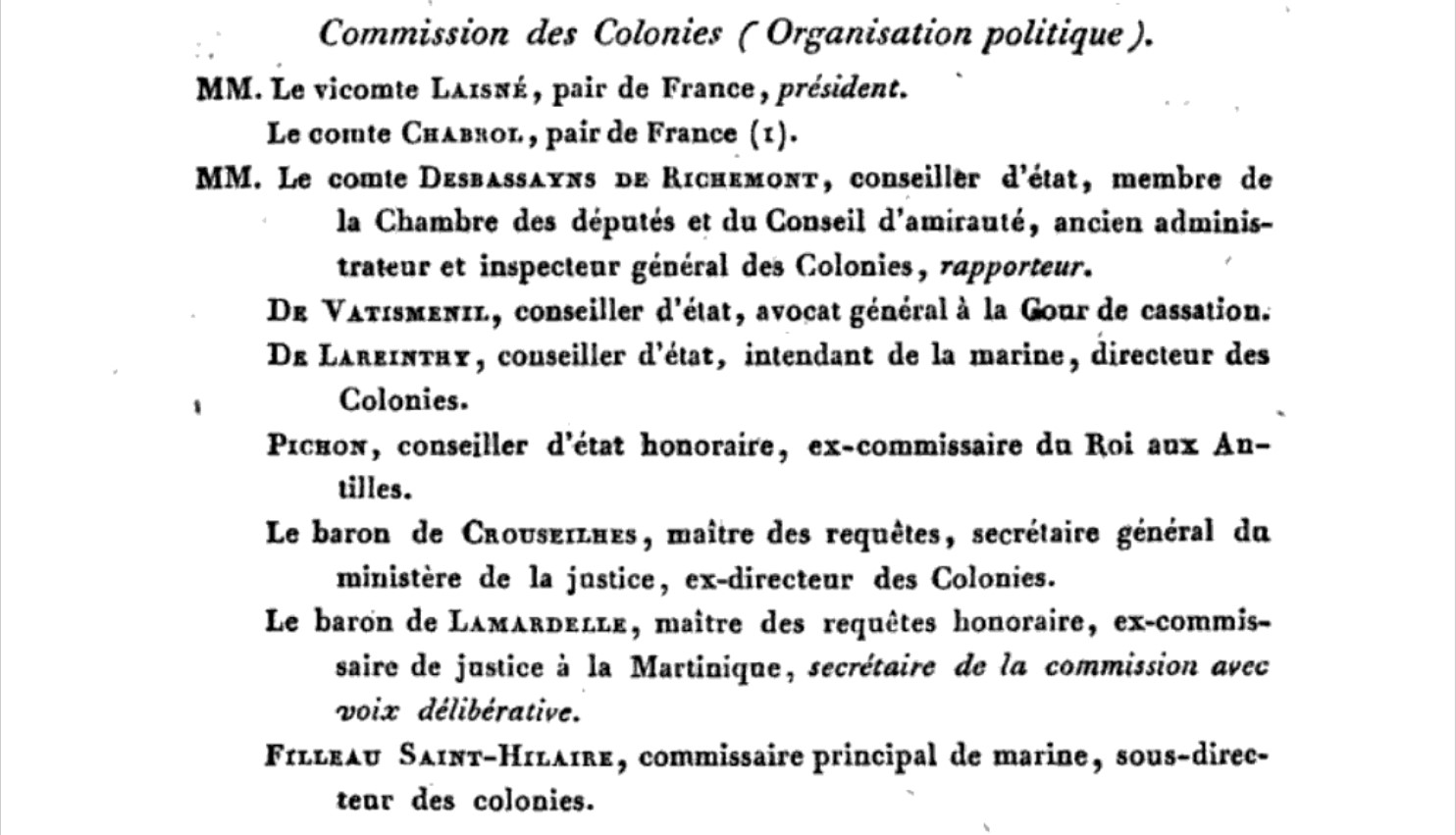

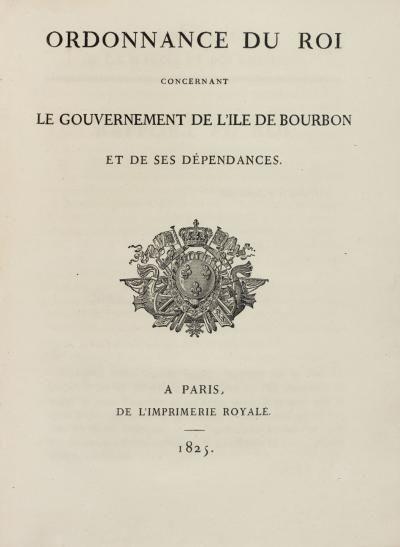

In 1824, after having first consulted the colonies themselves concerning their requirements, two commissions were set up, aimed at reviewing their organisation, one concerning the administration and the other the legal system. The first commission produced the decree dated 21St August 1825 and the second that of 30th September 1827.

Desbassayns did not chair the administrative commission, but simply acted as rapporteur and was thus entrusted with the task of drawing up an initial project for the decree. At the same time, he chaired the commission for reforming the legal system in the colonies. He thus played a truly important role.

Desbassayns was also the island’s only settler sitting on the commission : he was born on Bourbon, where his whole family had a financial interests, including his De Villèle brothers-in-law.

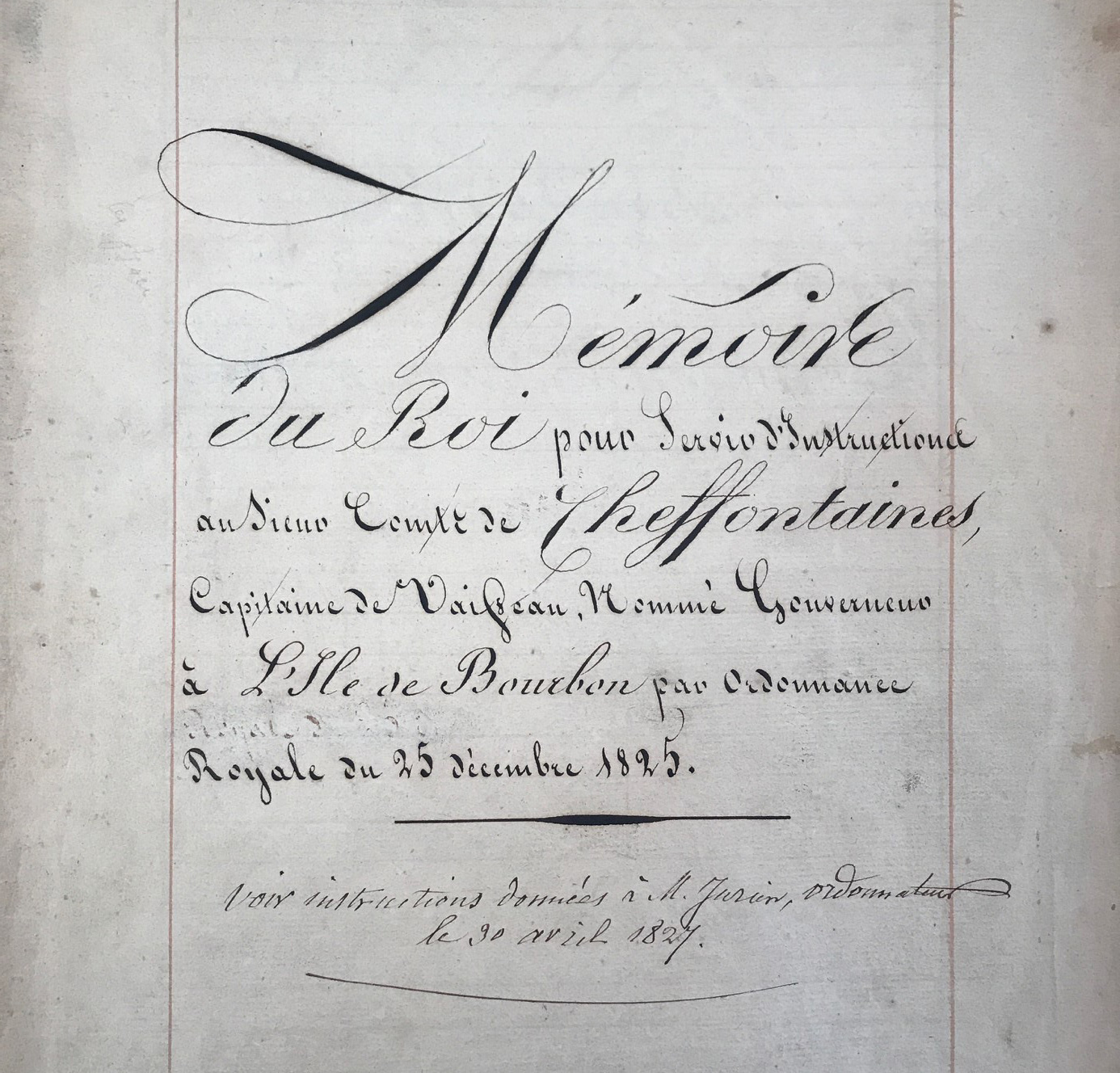

The new governor Cheffontaines passed the royal ordinance and counted on instructions from the king to apply it, in the true spirit of this new organisation, to be set up and applied as soon as possible.

The ordinance consisted of 195 articles organised under seven chapters, so was extremely detailed, which led to it being referred to as a “Code”.

The governor was placed at the head of the colony. He was the “depository of royal authority”, enjoying military powers, with powers at times resembling those of the head of State. His power to legislate was clarified. During the preceding years, the latter could issue “local” ordinances. Issues treated could give the impression that the governor had powers of a legislative character. The ‘Villèle Code’ limited this to executive power, noticeably through issuing decrees. Only the king and the parliamentary chambers enjoyed this power. However, in exceptional circumstances, the governor could make use of exceptional powers and thus provisionally apply texts normally sanctioned by the king, without this prerogative ever exceeding the duration of one year.

The governor was assisted by three heads of administration, who came under him in the hierarchy, but he could neither appoint them nor dismiss them, a prerogative reserved for the Minister of the Navy and the Colonies. The director of the interior was responsible for the interior administration of the colony, of the general police and administration of direct and indirect taxes. The commissioner-authorising officer was given responsibility for “services related particularly to the State, notably management of the Treasury”. The public prosecutor was responsible for the courts, but also for drawing up and issuing the governor’s orders. A colonial controller was also created to inspect and report on actions of the colonial administration in Paris. This civil servant had no powers in the colony, but the governor could do absolutely nothing to counter his activities.

The legislator also created a private council, the role of which was to support the governor in carrying out his tasks. It was composed of three heads of administration and two ‘colonial councillors’ appointed by Paris (the controller would attend all the sessions but had no decision-making voice). Delabarre de Nanteuil assimilated his role with that of the State Council under emperor Napoléon III. Avec l’adjonction de magistrats, le conseil privé se transforme en conseil du contentieux administratif, juridiction de droit commun du droit administratif de la colonie.

A General Council was set up with the aim of giving advice to the inhabitants concerning public affairs. It consisted of twelve members appointed by the king from a list of candidates presented by the town councils.

Finally, a Member of Parliament was selected by the king from a list transmitted by the General Council with the aim of representing the colony at the Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies. This representative thus did not sit on any of the legislative chambers.

The ordinance was a high-quality text in that it gave rise to an intelligent combination of powers with the aim of avoiding, as far as possible, institutional delays and conflicts. Malfunctions that had been the object of criticism in the past were thus limited.

What remains to be analysed is the scope of the legislation and above all who benefited from it: the island’s inhabitants or mainland France?

First of all, it should be pointed out that once the project had been drawn up, it had to be presented before several organisations for amendments, such as the direction of the colonies, which approved it as it was, mainly because Saint-Hilaire, director of the structure, was himself a member of the commission. The project was then presented before the Admiralty Council , which, after examining it for most of the month of June, also hardly modified the text. As from the month of July, the situation evolved to the extent that Desbassayns, even though he had drawn up the initial project for the text, himself decided to modify several of its articles. One of the issues concerned the powers of the General Council, since initially the council was to have examined and voted on expenses. In fact, on 19th August, the Admiralty Council came out in favour of a simple consulting role for the Council on budgetary matters, thus reducing its role to virtually nothing. The minutes of the Admiralty Council are strangely laconic concerning this radical change Two days later, the text was approved by the king.

This radical change in fact reflects a more general tendency of mistrust in respect of the colonies by the executive power in mainland France: allowing them certain liberties as regards their administration amounted to leaving the executive power once more open to dangerous decisions taken by revolutionary colonial assemblies. In order to leave no possibility of having an excuse for sedition, power had to be concentrated in the hands of the governor, or at least apparently so. In fact, while the latter occupied a prestigious and very highly paid post, he actually had very little power over his subordinates. He could appoint virtually no civil servant without the approval of the king, while his status prevented him from creating links (for example marriage) with the settlers. Thus, any risk of connivance or conflict appeared to have been removed. The governor enjoyed a large amount of freedom as regards public order (notably concerning slavery), but regarding purely administrative issues he could do virtually nothing without the approval of the private council, which he chaired but did not control.

Finally, it seems that Villèle was the one who ‘inspired’ the ordinance (with the active support of Desbassayns at his right hand). His intention was to reduce the autonomy of the settlers on the island, while leaving the governor with sufficient power for the latter to be able to maintain public order without it being possible for him to totally take it over or create links with the locals, which might lead to certain movements towards independence. The colony could then efficiently fulfil its role of enriching mainland France (and thus the settlers), by maintaining the system of Exclusivity, which was by no means something new. Thanks to his control over those drawing up the ordinance, Villèle could be assured of his wishes being achieved, as well as preventing Members of Parliament from influencing the provisions of a text that might not serve his interests or those of his clan.

In this respect, the ordinance has at times been highly criticised: “The private council was only set up by M. de Villèle through the 1825 ordinance with the aim of making the governors of the colony dependent on his family and his creatures, whom he made sure occupied the majority of the Council. According to the letter of the ordinance, the governor is declared to be alone responsible, even regarding exceptional measures debated by the private council, but in reality he always gives in under the powerful influence of the faction; this is how an oligarchy threatening the freedom of all takes over all the powers on the island.”

The 1825 Royal Ordinance remained applicable for over one century, surviving two revolutions, three constitutions, four different political regimes and even the abolition of slavery. Such longevity leads us to believe that its organisation had been well thought out, to the extent that it was later adopted in several other colonies. However, this flexibility is due to the many adjustments made to the initial version of the text, adjustments due as much to political adaptations as to evolutions occurring in the colony itself.

Very soon, the three other “old colonies” were given a new administrative organisation based on that applied on Bourbon island :

– Royal ordinance of 9th February 1827 applicable in Guadeloupe and Martinique

– Royal ordinance of 27th August 1828 applicable in French Guyana

Other colonies were the object of organic ordinances inspired by that of 21st August 1825, under the July Monarchy:

– Royal ordinance of 23rd July 1840 for establishments in India

– Royal ordinance of 7th September 1840 for establishments in Senegal

– Royal ordinance of 18th September 1844 for Saint-Pierre et Miquelon

As from 1828, small amendments were brought to the text, with the aim of adapting it to the important reform of the local system of justice.

In 1832, the General Council was modified following protests by small and middle-sized landowners determined to play a more important role in public affairs and encouraged by the liberal movement of the new July Monarchy. The governor Duval d’Ailly (appointed under Charles X) decided to accept a partially elected Council, going against the 1825 Royal Ordinance.

In 1834, the colony voted the law of 24th April 1833, which reformed the regime referred to as the legislative regime on the island. The royal ordinance of 22nd August 1833 set out a number of modifications to be applied to the 1825 text, notably adapting it in order to eliminate discrimination within the free population. The General Council was dissolved, to be replaced by the Colonial Council, elected by male census suffrage, playing an important role, which is also involved adjustments to the local executive power.

In 1848, the abolition of slavery necessitated important modifications, since many of the provisions of the ordinance concerned the institution of slavery. The Colonial Council was dissolved in the same year. The colony no longer had a local assembly, until the return of the General Council, made official by the imperial sénatus-consulte (consulting senate), itself modified on 4th July 1866.

Neither were the heads of administration spared. The function of commissioner-authorising officer was abolished in 1882, the majority of his powers being transferred to the director of the interior, whose function was in turn abolished by the decree dated 21st May 1898. The legislator placed a General Secretary alongside the Governor to take over the different roles that had been abolished, which brought the colonial system closer to the organisation on mainland France, since each Prefect in France is assisted by a general secretary. Only the role of public prosecutor was conserved. As regards the Colonial Controller, as from 1833, he was renamed “Colonial Inspector”. This function was finally abolished in 1873.

The Member of Parliament for the colony disappeared in 1834, to be replaced by two delegates elected by the General Council. The latter were not members of the French parliament either, as was the case under Napoleon III. It was the third Republic that brought back national representation for Reunion, representatives elected by universal male suffrage.

In application of the law dated 19th March 1946, Reunion became a French department and, through the decree dated 7th June 1947, was granted a Prefect. On 15th August, the governor André Capagorry was replaced by Paul Demange, the first Prefect of the department of Reunion. The colonial organisation was abolished, which put an end to the Royal Ordinance of 21st August 1825.