As from the years 1810-1820, François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose (1766-1846) showed an interest in the plain of Bois Rouge and grouped together plots of land forming the heart of the estate. To the first plot, purchased on 19th June 1810, he added eight others, thus creating an estate that covered over 100 hectares.

In January 1816 , there is mention of a still being used in Bois Rouge ,to manufacture sugarcane alcohol. During the year 1817, François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose set up the sugar refinery, listed in the 1818 census which mentions the production of 300,000 quintals (3 tons) of sugar. 40,000 g² (square ‘gaulettes’: square rods, equivalent of 100 hectares) were planted in sugarcane, 20,000 g² (50 hectares) with corn and 2,000 g² (5 hectares) with sweet potatoes. For the first time, included in the list of 121 slaves one is referred to as a ‘sucryé’ (sugar-maker). This was Jacquemin, a Creole aged 36. This is an interesting detail: it means that one of François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose’s slaves quickly acquired the know-how necessary for sugar manufacture.

The sugar mill at mill at Bois Rouge was powered using a steam engine manufactured in England, an essential innovation on Reunion island introduced by the brothers Charles and Joseph Panon-Desbassayns. François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose followed their example and in the early 1820s, Bois Rouge was the third sugar refinery to be equipped with a steam-powered mill. The governor Pierre Bernard Milius, who occupied the post on Bourbon island from 1818 to 1821, declared, concerning Quartier-Français:

There are several impressive sugar processing plants, notably that belonging to the Brun family [Quartier Français] and the one of Monrose Bellier [François-Xavier, Bois Rouge]. Monrose Bellier’s sugar refinery is remarkable in its organisation and economy. He brought in a pump from England, which reduces the labour-force required, but consumes a large amount of fuel .

The decision to use steam-powered machines “marked a radical change in the sugar industry around the world and placed the island within the industrial sphere.” […] The island adopted steam more or less suddenly and far sooner than Mauritius and the Caribbean Islands.” On Bourbon island, the industrial revolution had arrived, led by the development of the sugar industry: in 1810 there were just 10 sugar refineries on the island, with 91 refineries by 1820. In Saint-André, we can see from the censuses that there were 11 sugar refineries in 1818, with the number going up to 17 in 1823 . The district ranked second after Saint-Benoît .

From 1816 to 1822, the year of the last acquisition made by François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose on the plain of Bois Rouge, the area occupied by sugar cane on the estate increased from 12,000 g² (30 hectares) to 44,000 g² (110 hectares). The same figures for sugar production are not available due to a lack of precise data. There were also plantations of cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, crops used to feed the slaves on the estate.

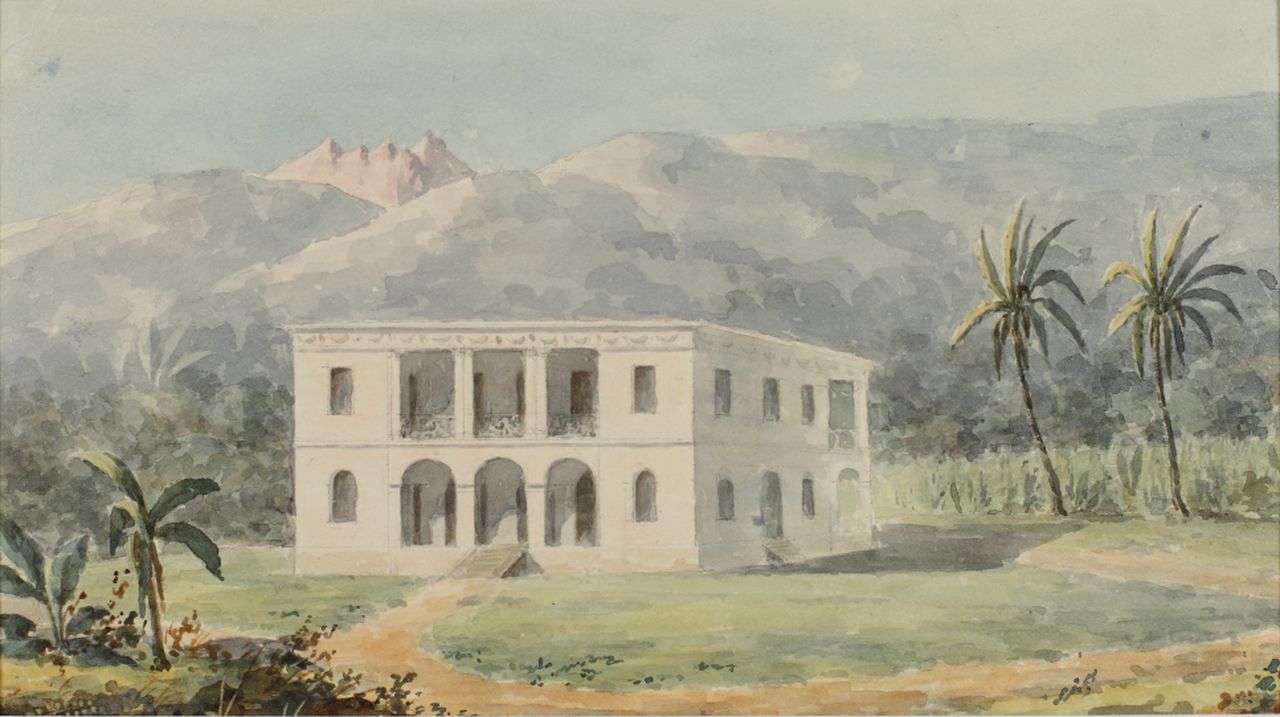

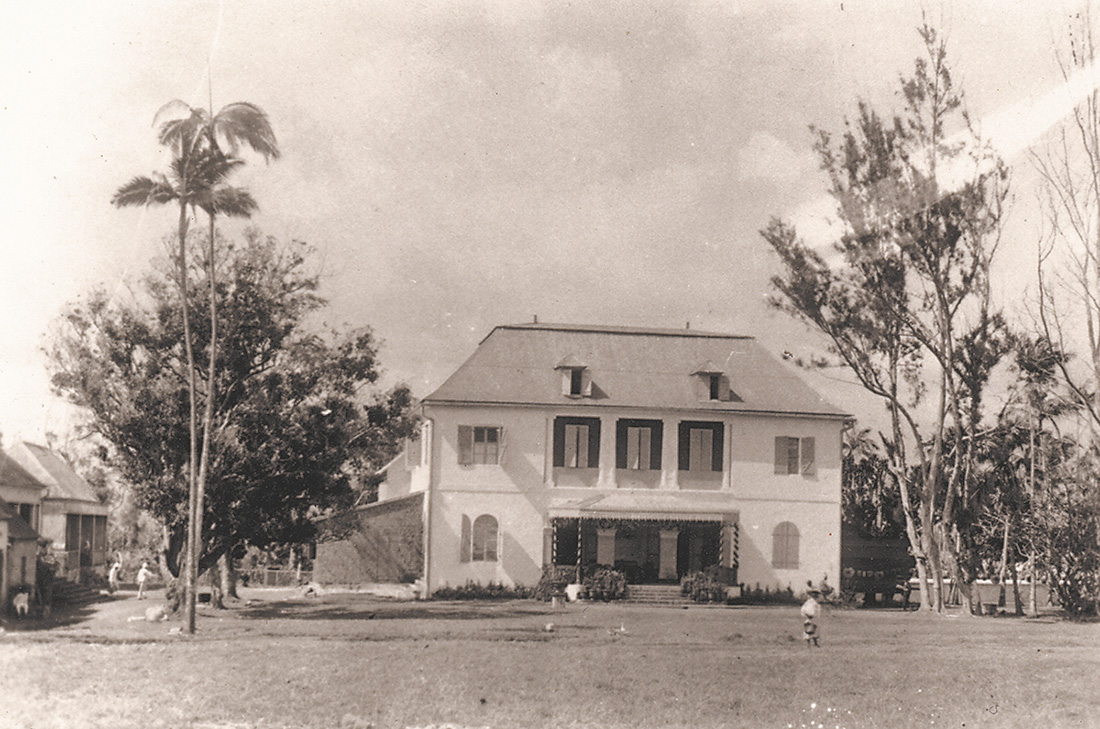

Around 1825-1826, the Bellier-Montrose family settled inside a large stone house constructed close to the shore and to the refinery. Probably designed following plans drawn up by Jean-Baptiste de Lescouble, the mansion, influenced by Neoclassicism, was one of the first important examples of this style in Reunion. The south façade, looking out over garden, as well as the original roof terrace, also follow the Neoclassical models of mansions constructed in Pondicherry at the end of the 18th century.

During the 1830s-1840s, Bourbon island experienced the first economic crisis of the sugar-cane era. In 1829-1830, three cyclones damaged the sugarcane fields as well as the buildings. In addition, the slump affecting sugar in mainland France, resulting from competition from beet sugar, referred to as ‘indigenous’ and the difficulty of obtaining the constantly increasing number of slaves necessary for working in fields covering a greater and greater area, put an end to the sugarcane boom experienced on Bourbon island in the first 20 years of the 19th century. A large number of planters were ruined, unable to pay off the loans contracted in order to purchase expensive equipment.

As regards the Bellier-Montrose family, the period was marked by the death of Anne de Boistel, wife of François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose in December 1830. The increasing economic crisis, as well as her death, saw the start of a difficult period for Bois Rouge.

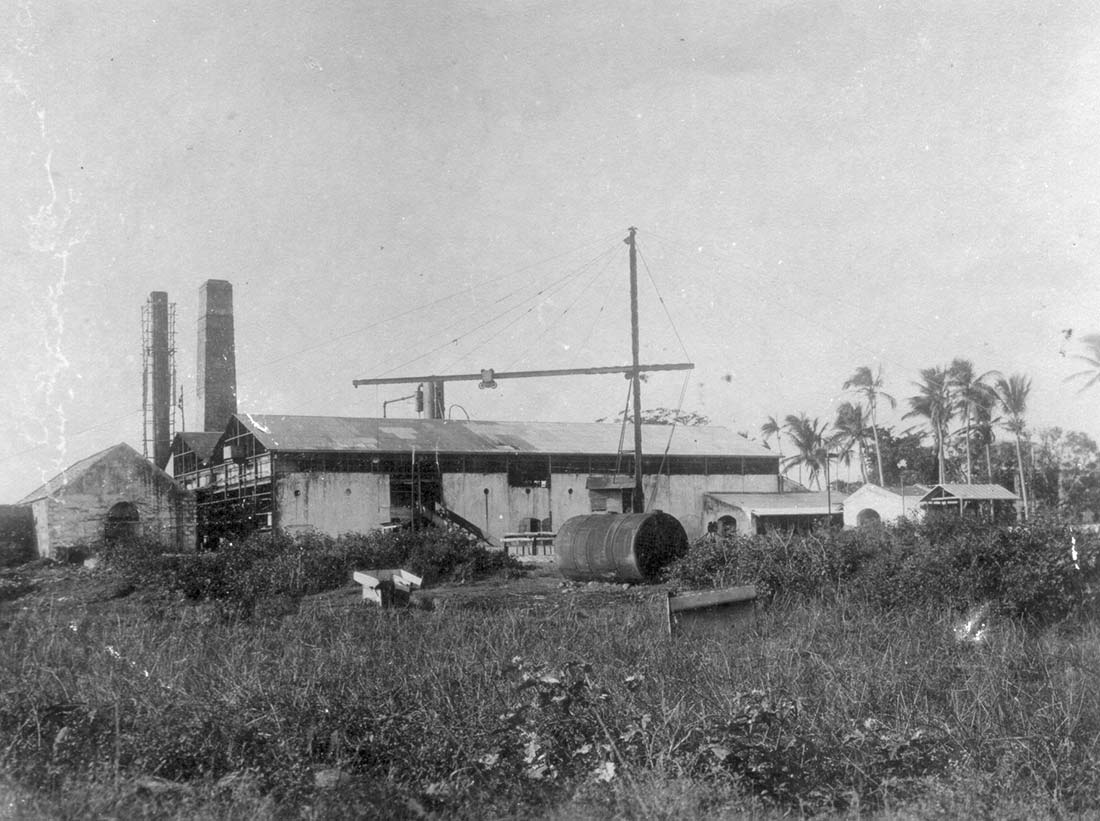

On 21st July 1831 , François-Xavier, then aged 64, owing money to 15 creditors, to an amount of over 1,700,000 francs, had no other option but to come to an agreement with his creditors in order to postpone repayment of his debts . Though he was able to continue living in the main house, as well as retaining ownership of 14 domestic slaves out of the 307 slaves living on the estate of Bois Rouge, the contract signed forced him to abandon ownership of the sugar refinery and the land of Bois Rouge for a period of four years. An ‘Inventory of the situation of the estate of Bois Rouge’ gives a succinct description of the site in 1831: two separate buildings, one housing the mill with a ten-horse-power steam pump, the other housing two batteries. There is also mention of ‘purifiers’, of two large warehouses ‘used for food and sugar’, a hospital, a smithy, several pavilions and a mansion. Two large buildings were used as warehouses and a harbour structure completed these installations.

The documents placing the estate under supervision indicate a record number of slaves for the period concerned: 307 individuals comprising 113 Mozambicans, 98 Creoles, 75 Madagascans and 21 ‘Malays’. The majority of these, 264 slaves, were in the age range of 14 to 60, 30 of the slaves (20 men and 10 women) were aged under 14 and 13 of them were aged over 60 (seven men and six women). There were more men than women: 213 men (69,3%) and 51 women (16,6%) in the age group between 14 and 60, corresponding to persons of working age.

The imbalance between the number of men and the number of women was not an exception: during the period 1810-1848, the average number of women present on the sugar estates was 24%. François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose, like other industrialists during this period, took the ‘option of productivity’, with over 210 men. The slaves were always under the direction of eight foremen, consisting of six Creoles and two Africans. In the long enumeration issued in 1831, there are the ‘esclaves à talents’ (‘professional’ slaves) and ‘Noirs de pioche’ (simple Black labourers): 12 ‘carpenters’, 15 ‘domestic workers or servants ‘, two ‘smiths’, one ‘shoemaker’ and finally one ‘cook’.

The measures applied in respect of Bellier-Montrose by his creditors did force him to renounce management of his estate, even on a temporary basis. 13 days after the deed signed on 21st July eighteen thirty-one, he borrowed the sum of 151,310 francs from three of his creditors, once more putting up the estate and its buildings as a guarantee. This irresponsible attitude, the duties to be paid on the estate and its indivisible character, as well as the departure of Adrien Bellier-Montrose, François-Xavier’s son, who had been much involved in the management of the estate, led to Bois Rouge being auctioned off on 5th February 1832 . The notarial deed contains a succinct indication of the boundaries of the estate:

to the north, the estate is limited by the legally defined coastal strip, to the south by Abadie, Deheaulme and Chambrun Maillot, to the east by the widow Maillot Chambrun and Ducros, and finally to the west by the former bed of the river Saint-Jean and the River Saint-Jean itself.’ There existed: “a two-storey stone mansion with a gallery, with all the outbuildings, harbour construction, with a stone warehouse and with rowing boats, dugouts and accessories, a sugar refinery, a purging room and a distillery, all in stone with all the utensils, a steam-powered mill used for the sugar refinery, a stone warehouse used as public storehouse for goods destined for export, stables, pigsties, chicken coops etc.

The deed confirms the scattered character of the industrial establishment. The manufacture of sugar took place in three separate buildings, a means of production imported from the Caribbean or Mauritius Island. Other sugar refineries on the island during the period show the same production chain similarly divided up between three buildings .

Bois Rouge was bought by Alexandre Pierre Protet (1798-ap.1855), François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose’s son-in-law, a former merchant navy captain who came from Saint-Sevran (Ile-et-Vilaine) and had settled on Bourbon island in 1827. Two years later, he married Aurélie Bellier-Montrose, (1809-1863), François-Xavier’s daughter and thus joined the circle of families of dignitaries living on the east coast of the island. He started working in Bois Rouge alongside his father-in-law as from 1831. The engineer Joseph Wetzell found him supervising the installation of “an iron pump for powering filters and taking measures to set up the harvesting process a few days later.”

During the years 1830-1840, Protet took an interest in other estates close to Saint-André. In 1837, he purchased Belle Vue, then in 1842, La Vigne, both important estates in Sainte-Suzanne. In 1845 he acquired shares in a second sugar refinery in Saint-André: la Nouvelle Espérance. Set up in 1835 by Emile Vincent and Frédéric Sauger, it was located on the right bank of the Saint-Jean river . This was the first central refinery set up in the colony in the 19th century, the first refinery with no land attached, prefiguring the evolution of the sugar industry in Reunion. It was also the most modern of the colony’s refineries, benefiting from a complete range of equipment provided by the workshops of Desrones et Cail, which equipped the sugar-beet industry in mainland France. Producing 1,000 tons of sugar in 1840-1841, La Nouvelle Espérance was the colony’s first sugar refinery, its production far greater than the island’s largest, which at the time produced 200 tons of sugar . These purchases were made to the detriment of Bois Rouge: between 1832 and 1848, Protet bought only one plot of land, of an area of nine hectares.

Regarding the slaves, in 1842 , there were 236 slaves living on the estate of Bois Rouge: 98 Creoles, 57 Madagascans, 64 Africans and 17 Indians. The group of Creoles made up the majority and continued to do so until the end of slavery, a consequence of reinforced controls regarding the illegal slave trade between the east coast of Africa, Madagascar and Bourbon island during the July Monarchy (1830-1848). Several slaves were specifically employed in the sugar refinery: Corneille, 40 years of age, and Adrien, both Creoles, were foremen and ‘chief sugar worker’; Bruneau, 44 years of age, a Creole, is listed as a mechanic ‘responsible for the mill’, Vulcain, 36 years of age, is the second ‘chief sugar worker’; Longol, an African aged 43, is listed as ‘mechanic’. These details reflect the evolution of the tasks on the sugarcane estates during the first half of the 19th century. Indeed, as from the 1830s, certain slaves among those on Bourbon island acquired the precious qualifications necessary for the functioning of the mechanisms of the sugar refinery , thus forming a sort of ‘elite’ among the members of the servile population.

The 1847 census , the last one that concerned Bois Rouge during the period of slavery, indicates: five hectares of Savannah, 35 hectares planted in corn, 52 hectares of sugar cane and 10 hectares of cassava. The corn crop produced 60 tons and sugar 250 tons. 219 slaves are listed: 104 Creoles, 49 Madagascans, 51 Mozambicans (Africans) and 15 Malays. Ten or so slaves were always specifically employed in the sugar refinery. There are several first names listed as from 1842, such as Bruneau, 49 years of age, a ‘mechanic’, Corneille, 45 years of age, and Adrien, 43, both Creoles, foremen and ‘chief sugar workers’. The latter were always supported by Vulcain, 41 years of age, a Madagascan, second chief sugar worker. Lubin, an African, a ‘foreman’ aged 53, completed this first team, as did Petit Jasmin, 31 years of age, an African, and Miliu, 41 years of age, a Creole, both mechanics. In the context of the system of slavery on Bourbon island, the simple word ‘worker’ seemed to be an anachronism.

Regarding the period between 1816 and 1848, the slave population on the estate of Bois Rouge increased greatly between 1816 and 1831, rising from 118 to 307 individuals, figures which reflect the development of the estate set up on the plain of Bois Rouge by François-Xavier Bellier-Montrose. From 1831 to 1847, the tendency was reversed, with 307 slaves in 1831 and 219 in 1847. This decrease can be explained by Alexandre Protet wanting to develop other estates that he purchased in the 1830s−1840s, but also a certain lack of interest in the site of Bois Rouge.

On 30th September 1848 , three months before the end of slavery, Protet sold Bois Rouge to a company consisting of his brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law for the sum of 446,204 francs, an amount which covered the 10 plots, with the ‘main house, steam pump, sugar refinery, warehouse and various buildings, 20 adult and young mules and several carts’, as well as 205 slaves. Adrien was the main shareholder, owning half of the shares, the other half being divided up between his brothers François-Xavier and Prosper Bellier-Montrose, his sister Marianne Bellier-Montrose, married to Léopold Auguste Protet, the heirs of the late Clémentine Bellier-Montrose, wife of Jules Henri Maingard, who were not yet of age, and Paul Maingard.

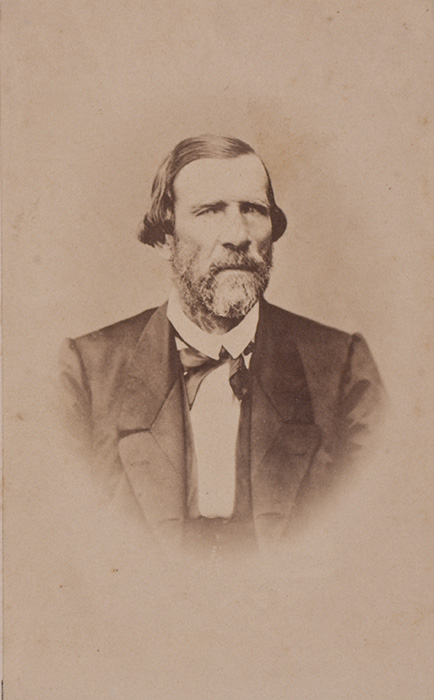

The company, the first in the history of Bois Rouge, was dissolved in March 1853: Adrien Bellier-Montrose purchase the shares owned by the members of his family for the sum of 342,857.12 francs. At the start of the Second Empire, he possessed 100 hectares at Bois Rouge and 207 hectares on the slopes above Sainte-Suzanne (an estate named La Réunion, purchased in 1838), both sites having a sugar refinery. These industrial establishments were among the 274 refineries set up on Bourbon between 1783 and 1848 , many of which were short-lived.

From 1851 to 1861, exceptional climatic conditions protected Reunion from damaging cyclones. In addition, the planting of new varieties of sugar-cane improved yields, increased still further through the large-scale use of guano, a fertiliser imported from Chili. As from the 1850s, the servile workforce that had partly moved away from the large sugarcane estates, was replaced by free workers under contract, ‘indentured sugarcane labourers’, most of whom were recruited in India, but also in East Africa. During this decade, sugar from the colonies benefited from tax exemptions when imported to mainland France, thus facilitating its sale on the national market.

In this favourable economic context, sugar production in Reunion, from 18,540 tonnes in 1849 increased to reach 68,469 tonnes in 1860. In 1856, Georges Imhaus, the owner of the sugar refinery of Rivière Saint-Pierre in Saint-Benoît, and representative for the colony in Paris wrote, regarding Reunion: “It is certain that the wonderful development of its agriculture and industry will not stop here” .

This short period of prosperity led Adrien Bellier-Montrose, like many other of the island’s landowners, to apply a policy of buying land. From 1853 to 1869, Bois Rouge became the nerve centre of an agro-industrial empire spread over five districts in the east of the island: Sainte-Marie, Sainte-Suzanne, Saint-André, Bras-Panon and Saint-Benoît. To the estate of Bois Rouge and La Réunion were added: L’Union, in Bras-Panon, purchased in 1857, Rivière des Roches, purchased in 1863 and the estate of Dureau in Sainte-Marie, that later took on the name of La Révolution and was purchased in 1869. Each of these estates had a sugar refinery.

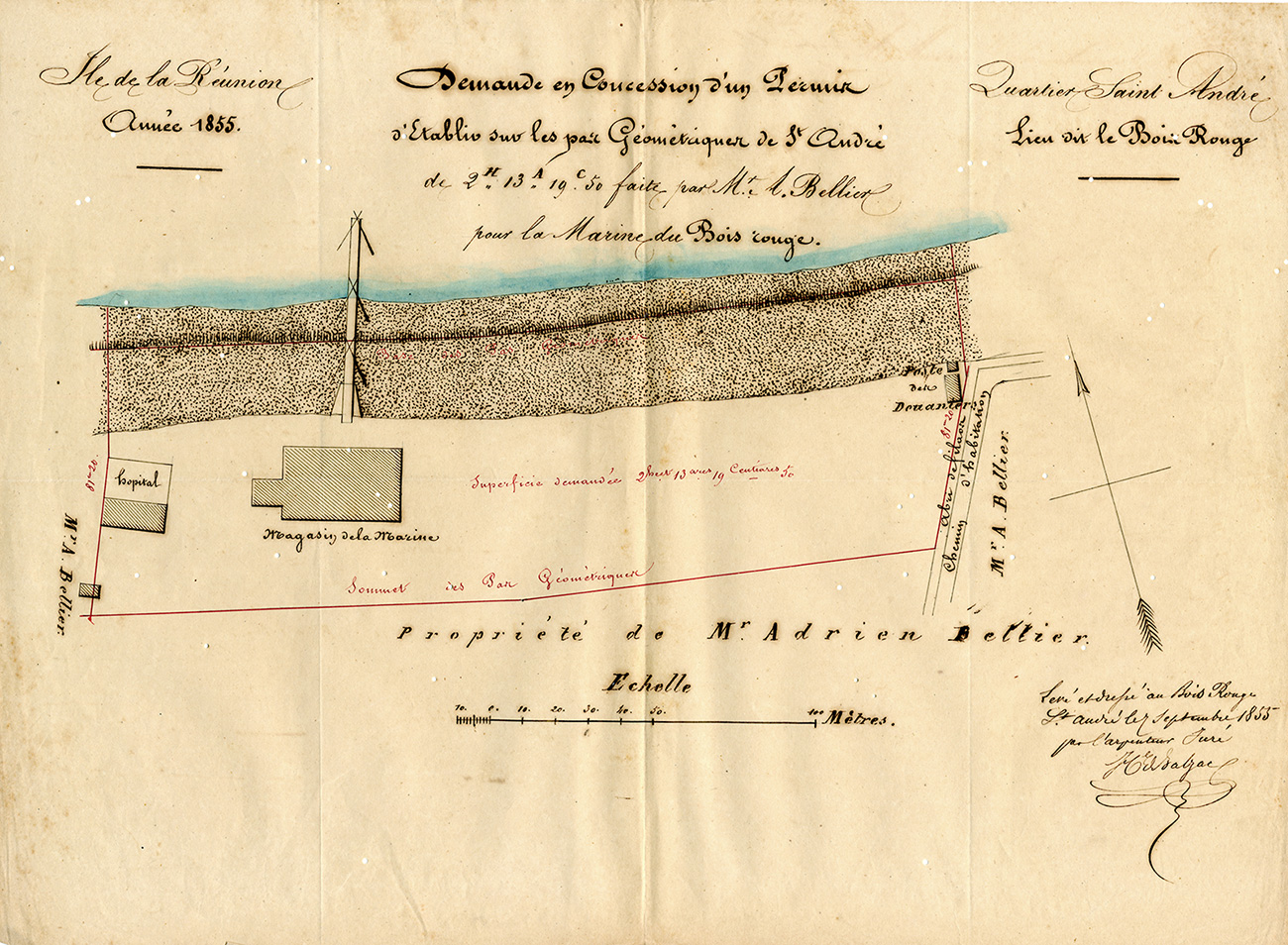

Regarding Bois Rouge, from 1853 to 1856, Adrien Bellier bought five large plots covering a total area of over 200 hectares: he tripled the area of his estate in Saint-André. In 1855, in order to be able to export his sugar, Adrien reopened the harbour of Bois Rouge, which had been closed since 1842. The harbour had three boats, carrying 10 to 12 barrels.

At the end of the Second Empire, Adrien Bellier owned several hundreds of hectares in the east, as well as five sugar refineries. His desire to acquire land was comparable to that of other families on the island who continually purchased land during this period. As a comparison, we can take the example of the families Orré, Choppy or Le Coat de K/véguen, who built up vast estates in Saint-Pierre, Petite-Île or Saint-Joseph. However, the prosperity of the 1850s was short-lived. A number of persons in the colony were expressing concern about land being grouped together in the hands of just a few families, the inconsiderate extension of land planted with sugar-cane to the detriment of food crops, but above all the excessive debts run up by the industrialists.

In 1862, the engineer Louis Maillard wrote: ‘Invasion by sugar-cane lies behind the fortune of the colony. Is this good or bad? The question remains […] we are still convinced that sooner or later sugar-cane as a crop will disappear […]’ . One year later, the economic situation started to become extremely unfavourable: Reunion exported 47,800 tonnes of sugar in 1863 compared to 61,564 the previous year. The drop in the price of sugar globally, the end of tax exemptions for sugar from the colonies, a series of destructive cyclones and the development of the chilo, an insect destroying the sugarcane fields, led to a decrease in production which, between the 1870s and the 1900s, varied between 20,000 and 40,000 tons. Towards the start of this new crisis, Clémentine de Heaulme, wife of Adrien Bellier-Montrose, wrote in her diary “Truly, this year from November 1864 to December 1865, has been extraordinarily fertile in disasters of all kinds: falls and ruin, […] Every year, we no longer have any harvests and are constantly disappointed in all respects” .

To survive, it was now urgent to modernise in order to remain competitive and to borrow the money needed to transform the island’s sole industry, now on the decline, with its frequently obsolete equipment. It was in this unfavourable economic context that Adrien Bellier-Montrose requested a loan of Fr.1 million from the Crédit Foncier Colonial. Set up on the island in 1863, this bank proposed a new type of loan: long-term loans, over 20 years at a favourable rate, unlike the rates hitherto applied in the colony. However, these loans were granted reluctantly and following the signature of a very strict contract that defined in detail the clauses of annual repayment of the amount borrowed and always covered by the guarantee of the borrower’s property. A contract setting out the terms of the mortgage was drawn up on 31st October 1864 . Bois Rouge, covering a total area of 314 hectares, was divided up into four adjacent units of land including the main one, “the Bois Rouge estate” itself. It consisted of 10 plots with boundaries:

to the south with the plots of Quartier-Français and La Ciotat, forming the second and third “estates”, to the east Grand Etang and the fourth estate named Nétancourt, to the west the river of Saint-Jean and the plot of La Ciotat, to the north limited by the sea and the rest by the estate adjacent to that of Mr de Kervéguen”. The following buildings stood on the site: “a sugar refinery constructed in stone with a tile roof; a large stone building with tile roof, used as a distillery with machines, equipment, stills etc.; a harbour establishment with a pontoon and various objects for its use, known as ‘Marine de Bois Rouge’; a large two-storey stone and timber warehouse with a zinc roof; a stone warehouse with a zinc roof; a stone warehouse with a tiled roof used as a smithy and a warehouse, divided up into several sections; a stone construction with two wings used as stables with a tile roof; several large stone huts with tile roofs, used to house 400 indentured labourers; a mansion referred to as ‘Château du Bois Rouge’, constructed in stone with a ground floor, first floor and second floor under the rafters with a wooden shingle roof; to the east, a wooden pavilion with a wooden shingle roof.

The 1864 sugar refinery was a unique construction covering an area of 1,000 m². The English mill, dated 1810 (steam, six horse-power), then 1840 (steam, ten horse-power) ,was replaced in the mid 1850s by a twenty horse-power mill manufactured in the French workshops of Desrones et Cail. A tubular generator of 100 horse-power and two reverse-flame generators, each of 50 horse-power, were used to provide steam to power the refinery. The power of the mill or generators contrasted with the archaic character of the boiling equipment for the vesou. Two ‘Gimart batteries’ a continuous boiling process developed in the 1820s by a local sugar producer Stanislas Xavier Gimart, continued to be used while other, more modern, boiling equipment was present on the island. Two vacuum boilers of the Nillus brand completed the boiling system. Once the sugar had been boiled, it was put through eight steam turbines, newly brought into Reunion in the 1840s.

Five years after signature of the loan, on 4th November 1869, Clémentine de Heaulme, Adrien Bellier-Montrose’s wife, died in Saint-Benoît. On 7th March 1870, François Mottet, notary in Saint-Denis, visited Bois Rouge and the various estates owned by the couple in order to draw up an inventory following her death. The document gives us essential information concerning the worker-force on the different estates belonging to Adrien Bellier-Montrose. 901 indentured labourers are listed in the inventory, comprising 283 at Bois Rouge, 118 at La Réunion, 280 at l’Union, 200 at la Rivière-des-Roches and finally 120 on the estate of Sainte-Marie. Amongst these, at least 452 were Indians, 46 were Africans and 23 Madagascans, figures which are incomplete since the distribution by ethnic group for the estates of l’Union and Rivière des Roches is not indicated. 250 Indians, 20 Africans and 13 Madagascans were living in the ‘camp’ of Bois Rouge.

0n 27th July 1873, an auction put an end to the complicated legal situation which had existed for four years between Adrien and his children. For 2,480,250 francs, he purchased Bois Rouge, La Réunion, l’Union and Rivière des Roches, thus avoiding the division of his ‘empire’. The estate of Dureau in Sainte Marie now belonged exclusively to Emile Bellier-Montrose, his third son. Adrien managed his properties with the support of the members of his family until he died at Saint-André on 7th August 1891, at the age of 85.

An industrialist and landowner, Adrien Bellier-Montrose also became an important political figure in the colony in the 1830s until he retired from public life in 1879. A member of the Francs-Créoles under the July Monarchy, he represented the colony from 1857 to 1859 at the ministerial Permanent Council of the Colonies.

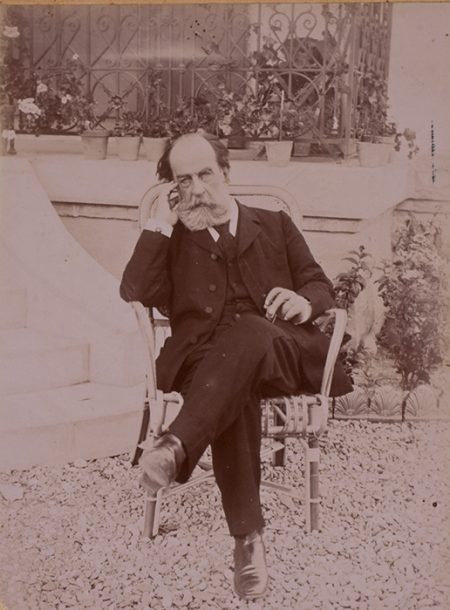

The Bellier-Montrose heirs were tempted to divide up the vast areas of land that they had inherited, but decided to defer the process and in 1896 entrusted the general administration of the sugar processing plants and estates belonging to them to a member of the family: Emile Bellier-Montrose, (1837-1905), who settled in the mansion at Bois Rouge.

Under the direction of Emile Bellier-Montrose, the sugar refinery increased in size, as can be seen from two photographs dated 1897 and 1904. The refinery was partly reconstructed and extended and several buildings were put up on the sugar−cane reception platform. However, the lack of documents in the archives prevents us from defining the exact nature of these alterations.

Following the death of Emile Bellier-Montrose, from 1905 to 1912 the family’s estate was administered by Armand Benjamin Barau (1860-1936). This former lawyer of the court of appeal in Saint-Denis married Anne Marie Ollivier (1866-1926), one of Adrien Bellier-Montrose’s granddaughters in 1889. Barau learned the profession of planter on the estate of l’Union, an estate belonging to his wife’s grandfather, an estate that he managed following his marriage.

In 1910, he asked the engineer Albert Chassagne (1870-1940) to carry out various improvements on the sugar refinery. Then in May 1911 he asked him to draw up a restructuring and extension project for Bois Rouge . Chassagne had solid experience in the field, since he worked for most of the industrialists on the island’s east coast. He drew up reconstruction plans for the sugar refinery of Rivière du Mât, entirely destroyed by a fire on 17th September 1908, and was in charge of supervising the work on the refinery from 1910 to 1911.

His project for Bois Rouge consisted in totally altering the external architecture of the sugar refinery, as well as carrying out alterations to the interior, retaining the position of the equipment while planning the addition of new rooms to virtually quadruple its size. Barau sent Chassagne’s project to the Fives-Lille establishment, who submitted their quotation in September 1911.

The work was carried out between 1912 in 1913, during which period, on 26th July 1912, the Bellier-Montrose heirs founded a limited company: the Adrien Bellier Company (Société Adrien Bellier: SAB). The capital comprised the land belonging to Bruguier in Sainte-Marie, the plots of Bois Rouge, La Réunion, l’Union and Rivière des Roches, and the sugar refineries of Bois Rouge and l’Union, all of which was estimated to be worth 15,120,000 francs. It was divided up into 1,512 shares of a value of 10,000 francs each.

As from 1912, while the destiny of Bois Rouge remained connected to that of one family, the creation of the limited company SAB opened up a new chapter in the history of the sugar refinery, that of 20th century limited companies.