Due to a lack of manpower, some planters sent representatives to Africa with the mission of buying slaves and freeing them on the spot before having them ‘sign’ employment contracts that could last 10 years, or even with no time limit. Formally, these enlisted men and women were known as ‘indentured’ workers. In reality, this was slavery in disguise, and would take about thirty years to finally disappear.

As a result of the Abolition, the entire economic organisation of the island was shaken. For the government and the planters, the first priority was to reorganise the plantation economy with new foundations (I). Its operation would require the creation of a bank (II). The transformation of the plantation economy led to the emergence of a small commercial sector and the creation of small farms. In addition, the Freedmen who were not part of the plantation economy had to organise themselves in order to survive (III). Contrary to fears at the time, the abolition of slavery did not lead to an economic catastrophe – quite the opposite (IV).

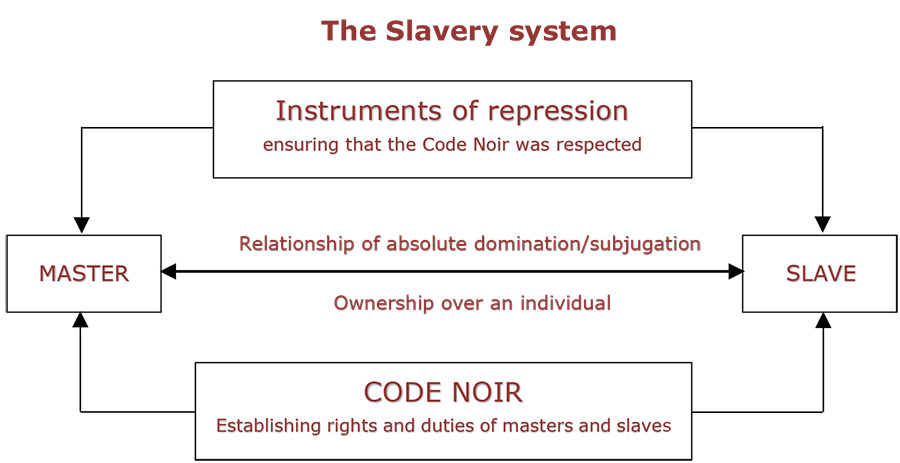

Slavery is a relationship of absolute domination/subjugation established between two people, one of whom is the owner of the other. When this relationship is widespread, this then becomes the basis of an economic and social system, and a set of rules setting out the rights of masters over their slaves is created and instruments of repression are put in place to enforce them.

In Reunion Island, slavery was put in place progressively between the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century. But it did not take its final form until the Code Noir was enacted in 1723. Its aim was to enable the French East India Company to set up coffee plantations and to make a fortune by exporting coffee to Europe.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the coffee plantations were destroyed by cyclones and the English took over Mauritius, which until then had provided France with sugar. Planters in Reunion Island jumped at the opportunity to develop their sugar economy, which at the time was still in its infant stages. In 1848, the sugar estates of Reunion Island operated on the basis of a slave system which can be represented as follows.

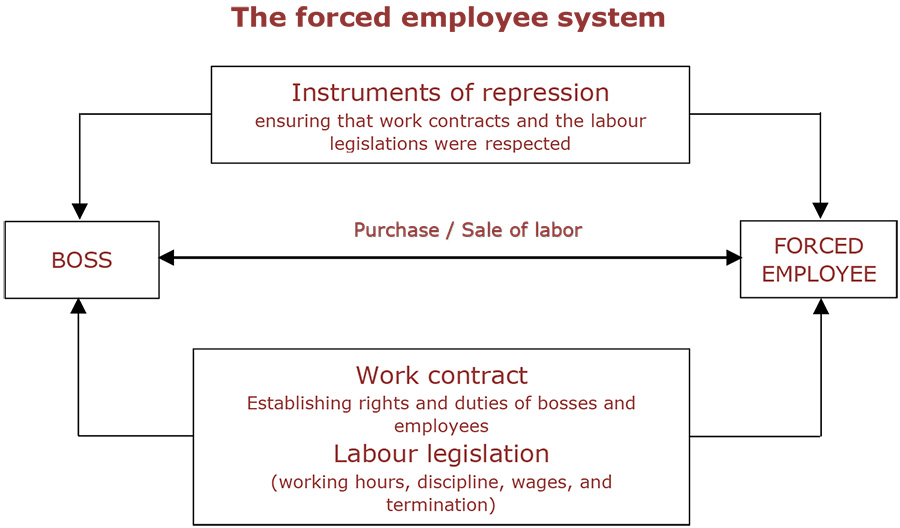

After 1848, this model had to be completely rebuilt because the masters had become ‘bosses’ and their slaves had been freed. In real terms, this meant that the masters’ ownership of their slaves was abolished and the Code Noir, which no longer had any reason to exist, disappeared. From then on, it became essential to set up a different employment system based on the buying and selling of the labour force of the immediate producer. At the same time new legal rules had to be created to formalise the relationship between employers and their workers.

Nothing changed in the field of technical labour relations: ‘gangs’ of workers laboured hard, following the orders of their supervisors. Tasks to be performed and working hours were no different than during the time of slavery. But what did change fundamentally was the social status of the producer – he was no longer a slave but a forced employee who:

• was legally free yet deprived of all means of production ;

• was allowed to temporarily sell his labour in exchange for a salary;

• had an employment contract defining both salary and working conditions;

• had a contract which ran for several consecutive years, and which could not be terminated at any time: hence the use of the term ‘forced’ instead of free employee.

The table below specifies the differences between the status of slave and indentured worker.

| Liberties and rights | Slave | Indentured worker |

| Religion | Compulsory adherence to the Apostolic and Roman Catholic religion. | Free |

| Marriage | With the permission of the master. Prohibition of interracial marriages and marriages between Freedmen and slaves. | Free |

| Right of assembly | Prohibition of gatherings between slaves of different properties | Limited freedom |

| Commerce | Prohibition to buy and sell except with the permission of the master. | Free |

| Property | Slaves could not own anything. | Right of ownership |

| Travel | It was forbidden to leave the estate without the master’s permission. | Controlled travel |

| Legal Actions | No Legal capacity | Legal capacity |

The following diagram explains the forced employee system, creating the foundations for the future economic organisation that would follow slavery from 1849 onwards.

How was this new regime set up?

The forced employee system that applied to Freedmen was not set up in the same way as that for immigrants.

Freedmen: from forced and mandatory employee status to compulsory labour

This forced and mandatory employee status for freedmen was created by the law of 18th July, 1845. Sarda Garriga took inspiration from this, issuing decrees in 1848 and 1849 which forced all Freedmen to sign up for one or two years as workers with their former master. This labour system continued until December 1851. How was it applied?

A field survey shows that on 1st January 1852, two thirds of Freedmen no longer lived on plantations. How can we explain this considerable shift?

Employment can only function if employees are paid. However, in 1848, minor planters did not have the necessary cash flow to pay their workers. Admittedly, the decree that abolished slavery had admitted that compensation would be paid to all slave owners, but the law specifying this compensation only came into force on 30th April 1849. It granted each former slave owner in Reunion Island a sum of 711.59 francs per slave which, although lower than the average price of a slave , was sufficient to pay their wages. But it was paid too late: the first instalment (33.88 francs per slave) was not paid until October 1849, and the balance only between 1850 and 1852 .

Refusing to work for nothing, a large number of Freedmen deserted the sugar estates. This desertion mainly affected the minor landowners who became drastically impoverished.

However, this decrease in the number of indentured workers can also explained by the strategy of some planters who chose to drive unproductive or low-productive workers off their estates. During the time of slavery, masters also had to take care of any infirm or elderly slaves. After Abolition, this obligation no longer existed, and it was preferable to simply get rid of them and replace them with indentured workers brought in from overseas.

The table below summarizes the most common labour strategies used by planters.

| Planters’ strategies | Consequences |

| Pure demobilisation: Owners recruited neither their former slaves nor any migrant workers. | Production stopped. Freed slaves found themselves without shelter or food overnight. |

| Attraction-recruitment: Planters recruited demobilised Freedmen and immigrant workers. | Increase in the number of workers and extensive growth of the plantation. |

| Demobilisation-recruitment: Planters fired any unproductive former slaves and replaced them with immigrant workers. | The number of workers remained constant but production levels increased. |

For social and political reasons, it was no longer possible to maintain this forced employee system beyond 1851. From 1852 onwards, the government organised a system of compulsory labour that extended to all those who did not have their own livelihood, and a system of control was set up.

• Workers on agricultural and industrial farms had to have an employment contract.

• All others had to have a worker’s licence.

• Those who did not have these documents were considered vagrants.

In order to reduce crime and begging, the government extended national legislation regarding vagrancy to Reunion Island, giving this term a broader definition than in Mainland France so that it could be more severely punished. In fact, this legislation remained practically a lame duck, for the reason that the colonial administration simply had no means to enforce it.

The influx of immigrants and the development of forced labour

In 1815, the Congress of Vienna banned the slave trade. Although a clandestine trade was set up, this was not enough for numbers to remain stable in Reunion Island, which fell from 71,000 to 60,300 between 1830 and 1847. On top of this, the workforce was getting gradually older.

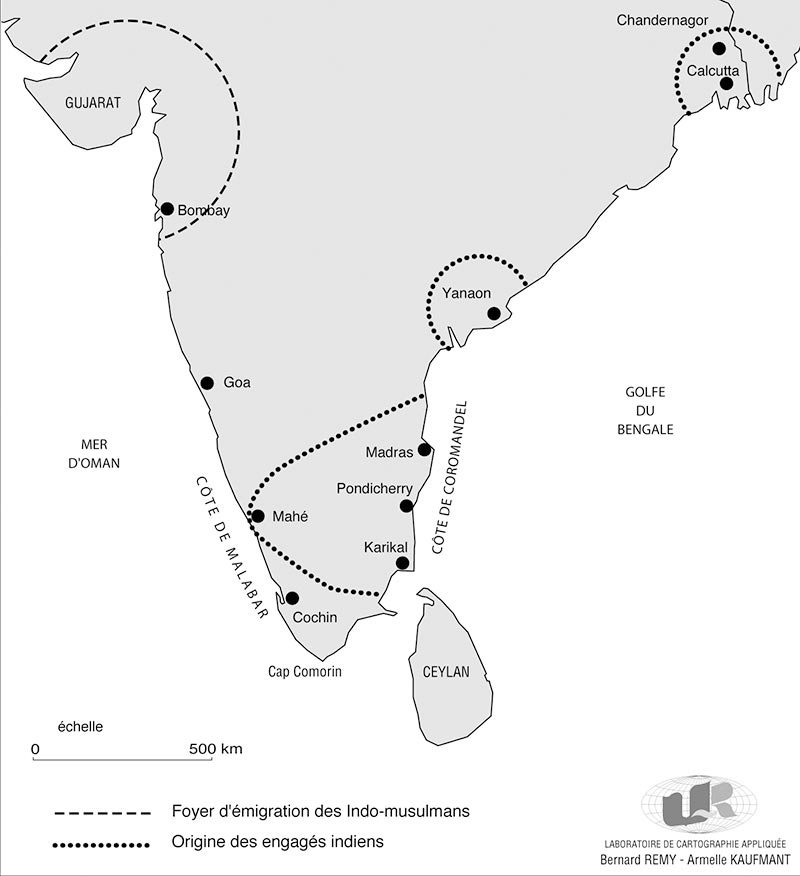

This is why, from 1828 onwards, the colonial administration and then the planters started to bring in indentured workers from India and China. A number of official laws were drawn up to establish labour relations. But this new regime was not able to develop: over-exploited, and treated just like the slaves with whom they worked, these indentured labourers revolted. Local authorities had to send them back to their respective countries and forbid any new recruitment of immigrants.

But after Abolition, it became essential to reopen the floodgates of immigration. Legislation was drawn up to organise recruitment, the transport of indentured workers, the logistics of their arrival in Reunion and their distribution among the planters… These indentured workers were employees who had voluntarily signed employment contracts that bound them to their employer for a long time (5 years). Part of their salary was paid in kind and part in cash.

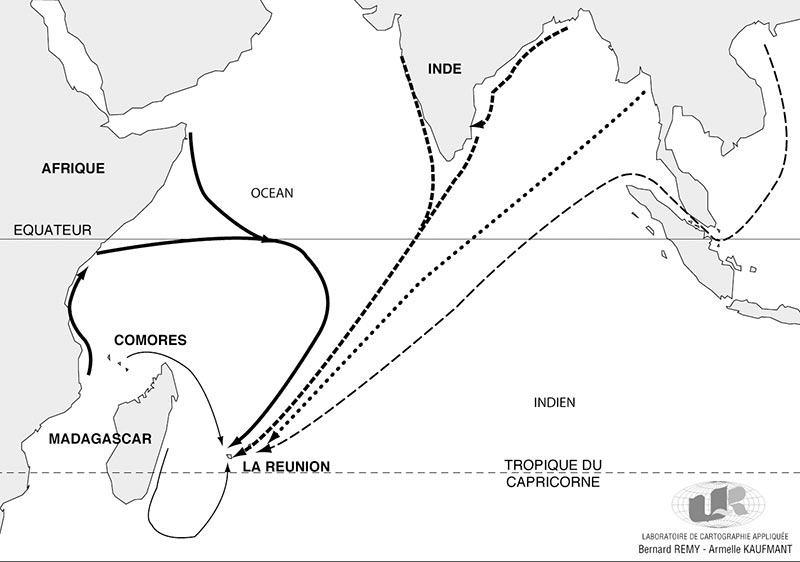

At the beginning, shipments of immigrants were made up almost exclusively of young and healthy men, and then the administration imposed a small percentage of women. In 1860, women made up 20% of the island’s workforce. Overall, between 1849 and 1881, nearly 150,000 workers were brought into Reunion Island, mainly from India, but also from Africa and Madagascar. In 1881, there were 46,450 of them, 20% of which were Africans, 65.9% Indians, 13.7% Malagasy and 0.4% Chinese.

Together, immigrants made up 30% of the island’s population. In order to feed the Indian workers who requested rice, planters had to import large quantities. Until then this had not been necessary, because the slaves had to be content with what their masters gave them. The maize they grew formed the basis of their diet.

The system of forced employees was carried out like a suction pump: planters would recruit them from abroad, and when they were worn out, they would simply send them back and hire new ones.

During the slave period, the market economy was very small and, given that slaves were not paid any money, planters did not need to have large amounts of cash available.

However, the new plantation economy needed credit and a sufficient supply of cash in order to operate correctly. In 1848, there was no bank on Reunion Island. Created in 1821, the ‘Caisse d’Escompte’ had been liquidated in 1826 and the ‘Caisse d’Escompte et de Prêts’ which replaced it also ended up closing down in 1834. To remedy this, Sarda Garriga created the ‘Comptoir d’Escompte et de Prêts de l’Île de La Réunion’ by order of 16th April, 1849. This bank did an efficient job, but its existence was short-lived. A law of 30th April 1849 ordered that a colonial bank of loans and discounts be set up in each of France’s colonies.

Established by the law of 11th July 1851, the ‘Colonial Bank of Reunion Island’ replaced the ‘Comptoir d’Escompte’. Known as the BR, it was a commercial bank: it could receive deposits, borrow capital and issue short-term loans. It also had the exclusive privilege of issuing banknotes, but these were only valid in Reunion. This currency was legal tender, which meant that all creditors, both public and private, were obliged to accept it as a means of payment. The privilege of issuing banknotes was an absolutely vital advantage as it meant that the BR could, in principle, issue as much currency as it wanted without having to bear any costs other than those of printing the banknotes. To prevent it from abusing this power, it was forbidden to issue banknotes in excess of three times its metal cash holdings.

BR’s initial capital was set at 3,000,000 francs. In order to raise part of it, it was planned that out of the 711.59 francs per slave to be received, former masters whose compensation exceeded 1,000 francs would receive seven-eighths of it, while the remainder would be retained to form the capital of the BR, of which they would become shareholders.

This establishment opened its doors in July 1853. Its creation was of paramount importance in that it facilitated the transition from the slave economy, which could operate with a very small money supply, to a capitalist economy that could only develop fully if it had a banking system capable of supplying businesses with credit and issuing a supply of capital which was in accordance with the needs of production and trade.

According to a survey carried out at the request of planters at the beginning of 1848, the total slave population working on farms which employed more than 10 slaves amounted to 48,698 people. 53% of them were men, 25.8% women and 21.2% children . What happened to them all after the Abolition? It is impossible to know precisely because there are no statistics governing them. This is normal given that from 1848 onwards there were only free people.

What is certain is that their integration into the island’s economy was extremely difficult. While slave owners were compensated, freed slaves received no such damages. It could be no other way – not only can one fail to see on what basis any compensation could have been calculated, but above all, allocating a plot of land or a sum of money to Freedmen would have enabled them to live off it and would have therefore made them independent. From then on, without a workforce, the plantation economy would have been wiped out, albeit momentarily, thus depriving Mainland France of sugar and in turn ruining all the farmers.

Some of the Freedmen left their plantations to head off into the hills and mountains where, since the end of the 18th century, groups of poor white colonists had started to settle. Like them, they too settled down and established a subsistence economy based on gathering and some rudimentary agricultural activities.

Some of the Freedmen were able to join society as common labourers in the main coastal towns. Others were hired by Freedmen of colour who had become farmers even before the Abolition. In fact, 5,865 slaves were freed between 1830 and 1847. Among them were 299 farmers who owned land and slaves to cultivate it.

However, many were not able to integrate normally into this new society. Just to survive, some women had no other option than to turn to prostitution. Children, the elderly and those injured in accidents at work became a sub-proletariat rotting on the outskirts of towns. When it opened in 1850, the first hospice in Saint-Denis saw the arrival of a throng of ‘sick, infirm and elderly people’ . Epidemics wreaked havoc among this population.

Unlike the slaves who were not paid in money and could not own anything of their own, indentured workers received a salary that they could spend as they wished.

Official documents from the 1860s bear witness to the existence of small landholdings held by indentured workers from India. Most often these were undivided lands owned by several people. The capital used to acquire them generally came from the savings that the indentured workers had put aside from their salaries. Moreover, at the end of their contract, some of them had also chosen to stay in Reunion Island and take small plots of land via a system known as metayage. This was a form of sharecropping through which the tenant had to produce what he was ordered to by the owner, which was almost always sugar cane.

The settler had free use of a small area to set up his hut, grow some food plants, and raise some poultry or pigs. The sale of these products provided him with income. This is how a small class of ‘farmer/sellers’ gradually grew.

During the period of slavery, the market economy was of little importance, as slaves were not paid in money, so demand across the local market was very low. Only large-scale trade was important and mainly concerned sugar exports.

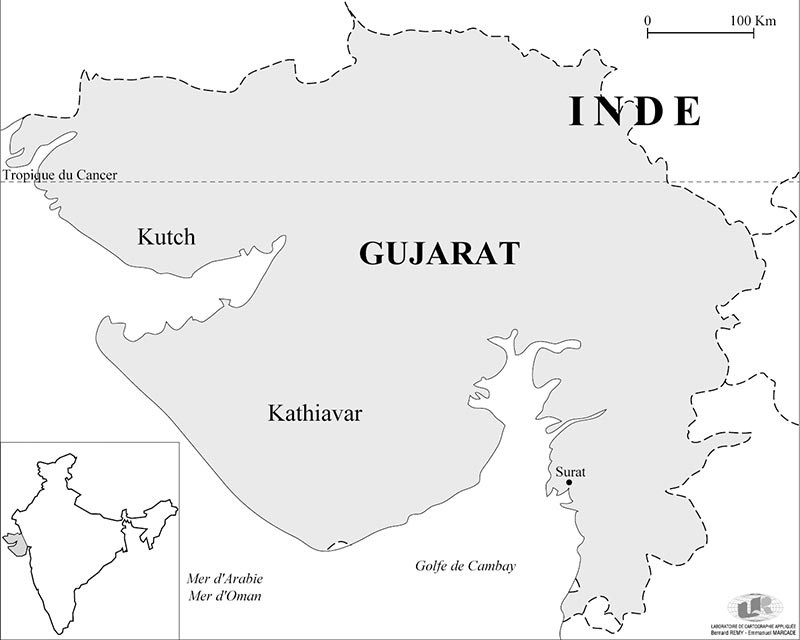

With the arrival of indentured workers, everything changed: these labourers received a salary which in turn increased the need for solvency within the local market. Admittedly, it was not very developed, because in 1859 there were only 65,000 employees in Reunion. But these numbers were enough to attract new immigrants to the island from Goujarat (India) and China, who began to arrive during the late 1850s and early 1860s.

These were not indentured workers recruited by planters, but people who came of their own free will to do business and settle in Reunion.

Indentured workers made up the bulk of their clientele. Chinese shopkeepers mainly offered food products, while Indian merchants specialised in fabrics and hardware items. In all cases, these were small businesses allowing those working there to just make a living, without making any profit.

The growth of the plantation sugar economy can be observed through its statistics. The table below shows the surface area of sugar cane areas, the increase in the number of workers and the rise in sugar production.

| Areas of sugar cane (ha) | Number of employees | Sugar production (tonnes) | |

| 1853 | 39 922 | 45 675 | 37 794 |

| 1859 | 64 207 | 70 457 | 61 978 |

HO Hai Quang, Histoire économique de l’île de La Réunion (1849-1881), p. 115.

At the same time, surface area devoted to food production was stagnating, as shown below.

| 1852 | 1853 | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 | 1857 | |

| Food | 33 831 | 32 209 | 34 107 | 31 038 | 34 120 | 23 137 |

Ministry of the Navy and Colonies, Tables of population, culture, trade and navigation over various years

As the number of mouths to be fed continued to increase with the arrival of new indentured workers (the island’s population rose from 100,000 inhabitants in 1850 to 178,000 in 1860), a shortage of food products became apparent and prices began to rise.

Reunion Island, once the ‘pantry of the Mascarene Islands’ and an exporter of food, started to have to import more and more. From 1840 to 1849, imports averaged 15.7 million francs a year. In 1859, this value had reached 42.6 million, almost tripling in just one decade.

Rice came from India, salted fish from Newfoundland, pulses and meat from Madagascar. In 1857, Reunion narrowly avoided a famine thanks to the introduction of duty-free food grains and the purchase of Malagasy rice at high prices. Learning from these events, the government took steps to encourage local food production.

1 – On the eve of the Abolition of slavery, the sugar economy was in the grip of a labour crisis. While Abolition initially made this worse, it also offered those planters (who could afford it) the opportunity to get rid of their unproductive slaves and replace them with healthy, young workers, mainly from India and Africa.

2 – Slavery, as an economic system, was replaced by indentured labour, which can be described as a system of forced labour. Its gradual decline, from 1882 onwards, led to the development of two systems of production: share-cropping in agriculture on one hand (metayage), and independent wage labour on the other.

3 – In addition, on the periphery of the plantation economy, and in connection with it, there was the emergence of a small retail trade (in the hands of the Chinese and Indo-Muslims) as well as micro-land ownership, the basis on which a class of ‘farmer/sellers’ gradually formed, which would continue to develop with the growth of share-cropping after 1882.

4 – From 1852 to 1960, the most powerful sugar producers were able to expand their estates, modernise them and thus increase sugar production. Fortunately, the price of sugar was rising and, for them, this truly was a golden age.

5 – While wealth was accumulating at one end of society, the other end of the spectrum saw indentured workers and Freedmen, who were not part of the plantation economy, living in misery. This economic growth was therefore exclusionary. Governor Darricau himself noted that:

“Everywhere I have been struck by sights that have touched me deeply: alongside the lushest of crops and most magnificent produce lies truly saddening shortages; wealth in a few hands, while the majority of the population has less than the bare minimum” .