The history of indentured Chinese workers has two periods: the first began during the mid-19th century, the second at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Suffren weighed anchor in Bourbon on 13th April 1844 with 54 Chinese men on board who had been enlisted at Pulo-Pinang in Malaysia. It was hoped that they would be the saviours of local agriculture – of course, the island had developed economically since its industry had turned to sugar in 1815, an activity which required considerable manpower, and on the eve of the Abolition of Slavery (1848), the owners and planters in Bourbon set out in search of labour. Given the forced opening of China to foreigners, they wanted to find Chinese workers to replace the Indians and made several requests for recruitment to the governor. The Colonial Council accepted the arrival of Chinese coolies on principle, and an order to this effect was signed by Governor Bazoche on 10th November 1843 . It was thus decided to bring “up to a maximum of one thousand Chinese labourers into the island”.

This first convoy was followed by others. Ships bringing in Chinese recruits arrived in quick succession throughout 1844. On July 5th, La Sarcelle arrived from Singapore with 69 Chinese recruits on board . 59 of them were sent to the Colonial Workshop where some were “assigned to building dykes on the Rivière des Marsouins, and the rest worked on protecting Rivière Saint-Denis” . The remaining 10 others were given silk farming work on M. Perrichon’s land in Salazie.

And so, contingents arrived one after the other, particularly from the region of Amoy. But this emigration would eventually slow down. On 2nd July 1846, Governor Graeb signed an order “suspending, except for operations already underway, any new introduction of indentured Chinese workers” . At the time, the colony was home to 458 such workers . Due to problems encountered, the planned figure of one thousand was never reached.

At the beginning of the 1840s, the local press spoke of the Chinese enlisted men in complimentary terms. For example, in 1843, La Feuille hebdomadaire de l’Ile Bourbon described them as “elite workers, indigenous to Asia”, claiming that “no race could compete with them”.

Not everyone was convinced, and some became disillusioned, making official complaints. As a result, Julien Gillot l’Etang sent a letter to the Council of Bourbon on 6th September 1844 to have two “bad, lazy subjects, incapable of any service” repatriated, and had them imprisoned while they awaited their departure . On 28th October 1844, a police inspector wrote a letter to the Director of the Interior, echoing the recriminations of recruits who had come to lodge a complaint against their employers . The situation worsened to the extent that on 2nd July 1846, the Council realised that “complaints about the Chinese are coming in from all sides. They are generally bad workers. They populate the jails and disciplinary workshops”. The following year, the situation worsened further.

Great disappointment was felt by their employers: the cost for each contract was much higher than they had expected, as noted in the minutes of the Colonial Council which described prices as “a discouraging exorbitance”. Moreover, these newcomers did not provide the assistance that had been expected and were hardly profitable: “They work slowly and have a violent temper”, wrote M. Féry, an employer in Sainte-Suzanne in 1849. This sentence summed up all the grievances of the planters. Their physical ineptitude was apparent in the description of an article in La Feuille Hebdomadaire de l’Ile Bourbon, which described them as “weak, malignant, and frail”.

Apart from their disappointment, these employers did not hide their anxiety caused by the violence of these Chinese workers, who would often resort to physical violence, a new experience for these masters used to more obedient and passive labourers. Gabriel de Kervéguen wrote to the Director of the Interior in 1848: “Today, insubordination has reached a peak: they threaten or even assassinate their foremen, and start fires wherever they find the opportunity (…) At my establishment in Les Casernes, they tried to kill Mr Ernest Lallemand, my employee. A Chinese man, employed in the factory, took one of my blacks in his arms and was going to throw him into a cauldron full of boiling syrup, and was only prevented from doing so by other blacks working there” .

As for the Chinese employees, they were exasperated by the treatment they received. On 28th October 1844, a police inspector sent a letter to the Director of the Interior, echoing the recriminations of these hired men who had come to file a complaint against their employer : “Eleven Chinese labourers working for Mr. Lacour living in Saint-André came in to complain that the conditions they had agreed with their employer have not been fulfilled…-1°) Food rations are not respected -2°) They are beaten by the foreman -3°) They start work at 7 o’clock in the morning and do not leave it until one o’clock – 4°) They are poorly cared for when they are ill and one of them, Assiov, died last night”. And he adds: “These people seem to me to be full of goodwill who regularly fulfil their religious commitments”.

Insufficient food rations, excessive working hours, violence and assault were just a few of the traditional sources of discontent, to which can be added claims related to the payment of wages: in 1847, for example, Mr Périchon’s Chinese workers demanded their unpaid salaries.

In 1962, journalists from Taiwan carried out an in-depth investigation published in 1966 under the title Liuniwangdao Huaqiaozhi 留尼旺島華僑志 “Monograph about the Chinese people in Reunion Island”. Presenting the Chinese point of view, the authors described this period in the following terms: “When they landed on the island, they were forced to carry out two types of work: the building of roads and silkworm farming. Shortly afterwards, a small group refused such conditions and fled into the mountains”.

And so the marginalisation of indentured workers became common, with many slipping into begging, vagrancy, and even delinquency. One example came from the workers of the Chinese Brigade. At the Colonial Council on 17th February 1846, one of the participants, Patu de Rosemont, declared that a certain number of them would wander the streets, “crossing properties in droves, stealing sugar cane and everything else they can take; and when guards show up to chase them away, they get harangued by insults and forced back by volleys of rocks” . Given such a context, delinquency was a logical consequence. Thus, many Chinese found themselves up in front of the courts to be judged for their crimes, so that “between 27th October 1847 and 26th January 1848, the justice system involved thirty-eight Chinese people in criminal acts, such as arson, robbery and murder” .

Expulsion became the classic technique used by colonial society to deal with these problems. In September 1844, a request was made by Julien Gillot l’Etang for the repatriation of two of his workers. This type of request became increasingly common. In November 1845, the Privy Council opened a debate on the expulsion of workers of the Chinese Brigade: the Civil Engineer demanded that fifteen of them be sent back, as they were “good for nothing”. On 6th March 1847, the governor’s order was signed, official expelling thirty of them back to Singapore . Other departures took place, without however taking such coercive forms.

This period marked a hiatus in agricultural work for the Chinese: for a long time, planters refused even the possibility of resorting to their employment, and it was not until the end of the century that more Chinese coolies were brought in once again. In addition, a negative image of the Chinese had been forged, marked both by the disappointment of the farmers and by the fear generated by their workers’ unexpected violence.

As for the long term, the first tentative steps of Chinese trade were beginning. Indentured workers starting to peddle and trade in food products. Bourbon’s enlisted men repeated the experience of those in Mauritius, where it was said in 1843 that: “… I was told that in Mauritius, most of the Chinese, also indentured, had given up on sugar cane farming. Some of them became peddlers, a vocation with greater benefits for them. Others, perhaps with more money, had apparently opened small shops” . Some of those who stayed on after their contracts had expired were interested in selling food and drinks near the factories, information revealed in the minutes of a meeting of the Privy Council in March 1858 .

Mauritius became a refuge for those who could not settle in Bourbon, and an attractive spot for those who wanted to earn a little money before returning to Asia. On the other hand, those who chose to stay on the island represented the grass roots of a stable diaspora. .

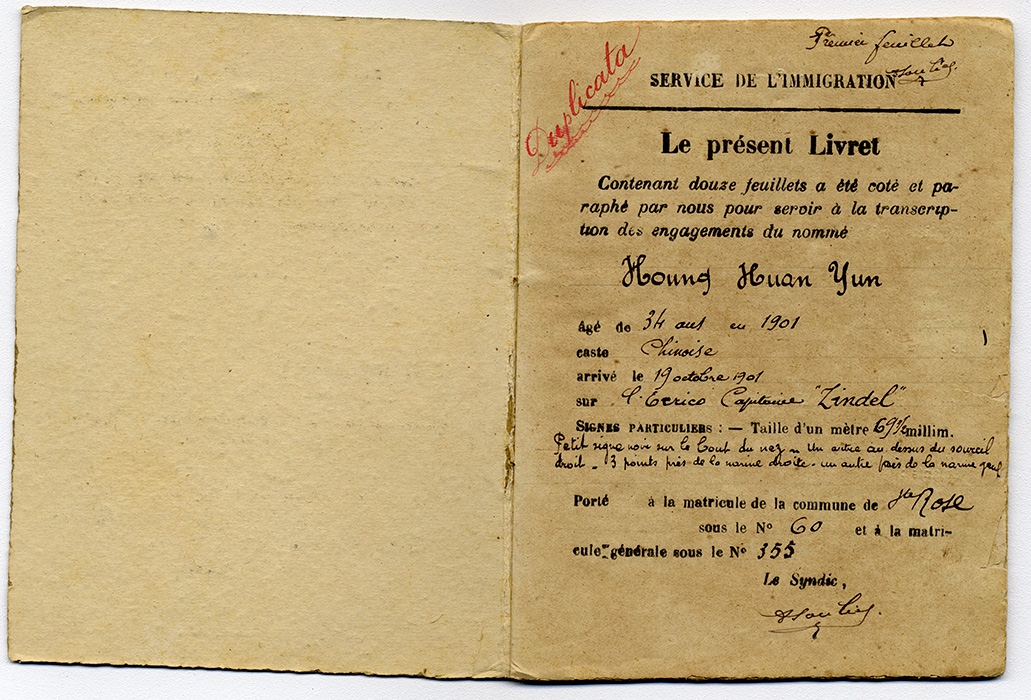

This took place when the 808 indentured workers arrived in October at Pointe des-Galets on board the Erica, having set sail from Fuzhou on 21st September, 1901. It does not seem that there were any other convoys after that.

The resumption of Chinese immigration was marked by successive conflicts resulting from the revolt of these men. Between 1901, the date of their arrival, and 1907, which marked the return of a large number to China, not a single year would pass without rebellious events taking place. The first took place as early as December 1901, with incidents that took place on the Colson and Kervéguen properties in Saint-Louis. In a letter dated 11th December 1901, Brigadier Dufossey informed his squadron leader of the Saint-Denis Gendarmerie of the following: “Today, the eleventh of the month, at around one o’clock, I was warned by an employee of M. de Kervéguen that the Chinese immigrants, who had recently arrived in the colony, were completely refusing to work. I immediately went with a Gendarme to the said establishment at La Rivière (Saint-Louis) (…). Out of forty immigrants employed by the establishment, half of them had called in sick that morning with the sole aim of getting out of work. The others started the day as best they could, grumbling, but when it was time for lunch, they gave the pretext that there was not enough food, and chose not to go back to work in the afternoon, despite the repeated insistence of their employers” .

Similar problems took place in the east on 8th January, 1902: a mutiny broke out in the Bois-Rouge establishment . and problems only got worse as time went on . On 11th June 1905, a fresh complaint was filed by 13 employees of the Bellier establishment . In 1906, discontent was widespread: in the east, movements were organised and the Chinese planned to march on the capital. During the same year, growing unrest spread to the south. In December, the property of Saint-Louis des Kervéguen was still the scene of mutinies. For the past three years, it had been employing former employees of the Chabrier estate. When their contracts expired in September 1906, they claimed their due from their employer. Mr de Kervéguen informed them that they had an exorbitant number of working days to catch up! Outraged by this, they sent a delegation of 25 men to the Governor in Saint-Denis on 25th September 1906 to explain their case and ask for protection. They obtained promises and assurances, along with the council’s recommendation that they return to work. They were transported back to Saint-Louis by train, but no promises were kept – on their return they were even subjected to sanctions. An accountant of the Kervéguen family had them beaten. Some were injured, others sent to court in Saint-Pierre and thrown into prison. On 18th December, 25 of them refused to go to work. On 14th January 1907, Foctiev (the ‘leader of the Chinese’) was obliged to write to the Governor himself in order to obtain the release of “21 Chinese men who were put in prison in Saint-Pierre for having left the establishment without authorisation to go and make their claims to the worker’s union” . A collective letter dated 9th February 1907 was sent to the Governor to submit the prisoners’ complaints and explain their situation .

Problems of wages, poor treatment and working conditions: the grounds for recrimination of these indentured workers were linked to the strict rules of the relationship with the oppressed and their oppressors that dominated the world labour in plantation society.