In order to satisfy the needs of a plantation economy that was often labour-intensive or to build their colonies’ main infrastructure, Europeans called upon ‘free’ foreign workers, recruited under contract to gradually replace the slave labour that was soon to disappear. The argument that former slaves would be incapable of working if not forced was used to justify national policies of introducing foreign labour. And so, Javanese, Tonkin, Africans, but above all Chinese and Indians left their homelands to earn a wage in the old colonies of the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean, but also in territories recently conquered by imperial powers across Africa, Asia and the Pacific.

Measures taken at the Congress of Vienna, as well as the abolition of slavery announced in 1848 by the Constituent Assembly of the Second Republic, suggest that a painful chapter in French history had finally come to a close. However, in the French colony of Reunion Island, the system of African indentured labour simply continued the torments of the slave trade, the former system disguised using clever legalese in order to satisfy the needs of sugar cane cultivation and the sugar industry. In fact, this production system that had propped up the slave trade for centuries remained dependent on an external workforce, and the same awful consequences ensued. On one hand, the slave trade had been banned since 1815, because governments had judged that it was contrary to morality and human dignity. On the other hand however, it appeared that this trade in human beings continued as the only means of providing colonies with labour. Many historians have already pointed to this “disparity between theory and practice that appeared the moment that European nations started showing signs of moral and civil responsibility ” .

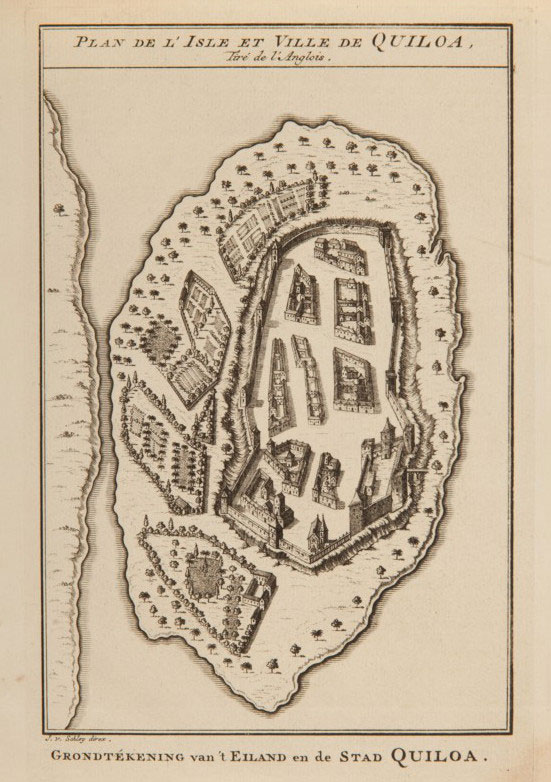

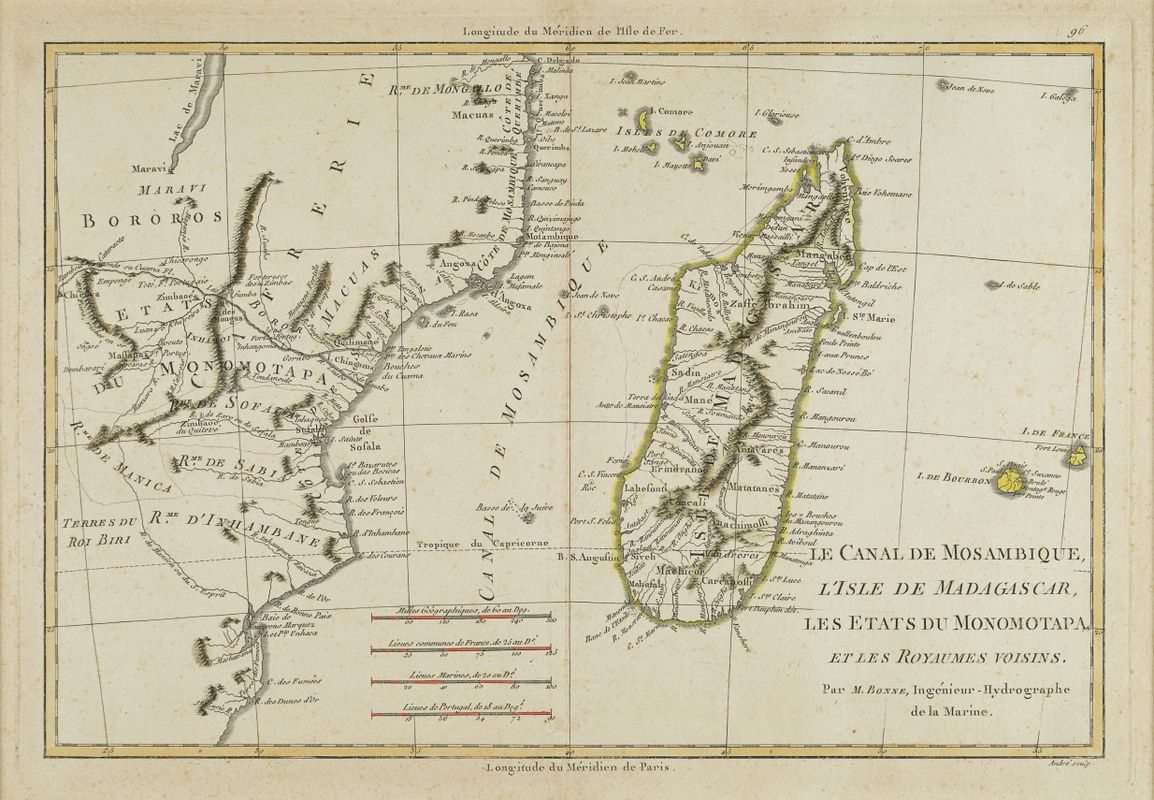

Even before the decree for the abolition of slavery was enacted, planters in Reunion Island brought in indentured workers from India. Unhappy with this experience, mainly because of the obstacles imposed by the British, but still convinced that ‘free’ immigrant labourers would be the saviours of the sugar industry, they turned to the African continent and in particular to the east coast of Africa, which for a long time had provided the colony with the manpower responsible for its prosperity. Following major purchases of slaves from Zanzibar during the 18th century, Reunion Island’s planters were already familiar with the east coast of Africa, and in particular the region of Kilwa (Quiloa).

The practice of recruiting indentured workers who hailed from the same place as former slaves was initially quite specific to Reunion, as those in the West Indies were much more reluctant to do likewise. As early as 1842, the governor of Reunion Island entrusted Lieutenant Le Mauff de Kerdudal, (commander of the brig Le Messager) with the mission of going to Quiloa to examine the resources that this part of the Imam of Muscat’s states could offer to colonists who wished to procure African workers. The commander delivered a report stating that captives could only be obtained by buying them from their Arab owners . However, in 1844, the Minister of the Navy and Colonies strongly condemned the purchase of slaves from the African coast putting an end to this practice. Numerous projects for the east coast were launched and then rejected by the authorities in Mainland France, albeit only officially. Humanitarian considerations, but above all the fear of being accused of perpetuating the slave trade, made the authorities extremely cautious. In particular, they feared reprimands from the British, to whom France had pledged to do its utmost to repress the slave trade and put an end to slavery. On 29th May 1845, France signed an agreement with England in which it promised to crack down on slave trading operations along the coast of Africa. Provisions were made for joint British and French boarding rights and consensual monitoring of slave ships, in an agreement which was signed for a period of ten years. In view of this commitment, France could hardly authorise the recruitment of captives along the African coastline for the needs of its colonial economy.

Following the abolition of slavery, and under a regime that was much less open-minded to the humanist principles of 1848, the government nevertheless evolved, but its position would become considerably ambiguous with regard to its own anti-slave trading laws. Up until 1855 (the end of the Franco-British agreement of 1845), the government’s attitude towards African immigration remained one of both caution and total hypocrisy. The young imperial regime did not want to fall out with the authorities in London and so the government limited themselves to a purely diplomatic stance, officially reiterating the prohibitions and restrictions on purchasing workers. These precautions were of course only respected on paper, for in practice the French government gave free rein to recruitment into Reunion, turning a blind eye to the awful conditions in which this recruitment took place. In fact, the obligation of recruiting only men who were free by birth (or had already been free for several years) seems to have been completely disregarded by the Reunionese authorities. Orders were ignored by ship captains who “went against the governor’s stringent wishes and organised a system of transporting slaves from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of Madagascar ” . It was a real priority for Reunion’s planters to make up for the loss of the island’s slave force in order to save its weakened economy, despite the risk of ignoring official government directives.

And so, between the abolition of slavery through to 1859, nearly 34,000 captives were transferred from the east coast of Africa to Reunion in order to satisfy the needs of an increasingly ambitious sugar industry. Rounded up in villages, then delivered to the African coast by Arab owners to French traders, these so-called ‘indentured’ Africans were nothing more than mere objects of trade whose lives had no more value than the price on their heads . Recruitment was a rushed affair, done without order and often completely illegally. Indentured labour from Africa was a way of continuing the existing trafficking of labourers, given that these indentured African workers destined for Reunion were nothing more than conscripted slaves, whose origins were never revealed by their recruiters. This upstream slave trade, coupled with the complete absence of any checks by the authorities (or worse, their complicity), made it possible to disguise the fraudulent and amoral nature of their business. Thus, Africans recruited on the coasts of Madagascar or Comoros were mainly slaves from Mozambique, Zanzibar or the regions under control of the Sultan of Muscat . The French territories of Madagascar and the Comoros saw both the arrival and departure of workers who were usually only passing through or in transit. As a result, the French islands of Mayotte and Nosy Bé become places of transit, trade and the trafficking of human beings. Here, contracts and conditions were fabricated in complete serenity. The contracts to which workers were bound would in no way represent any ‘freely consented agreement between two parties’ and immigration officers were more inclined to simply cover up the truth than to actually carry out any checks on the legality of these operations. Moreover, no Franco-Portuguese agreement authorising Mozambican nationals to leave for Reunion was signed during this period. Physical abuse, maltreatment and mortality on board ships made the recruitment and transport of African immigrants more akin to trafficking operations than to the Indian coolie trade. The French government and the local authorities turned a blind eye to this well-known trade, remaining happy to voice recommendations which were both illusory and hypocritical. The only efforts to protest against this abhorrent trade came from foreign powers who, under false appearances of philanthropy, were actually defending their own commercial and political interests. Worse still, it appeared that hindrances to French recruitment in Africa that came in the name of morality, as well as the lack of any clear framework from the French government, only served to exacerbate the criminal and barbaric nature of the whole business. Encouraged by Reunionese planters, recruiters were greedy for profit, and were happy to defy all prohibitions to get their hands on large numbers of indentured labourers. This precious human commodity would be recruited hastily, without order, and in the worst possible conditions. Thanks to these prohibitions and obstacles, potential recruits became rare and, as in any illicit trade, prices rocketed. Faced with labour shortages and under pressure from planters in the West Indies and Reunion Island, Emperor Napoleon III permitted the ‘pre-emptive purchase’ of slaves from any stretch of the African coastline in October 1856. The aim was to give official authorisation to a practice which had already been going on in broad daylight for several years and thus put an end to any ambiguity by formally allowing it to continue. No official publication related to this decision was published, an authorisation which would have been hard to justify. Hamelin, Minister of the Navy and Colonies, even put pressure on the governors of the West Indies and Reunion Island to keep the local press in check, ensuring that they didn’t delve too deep into any subjects related to immigration .

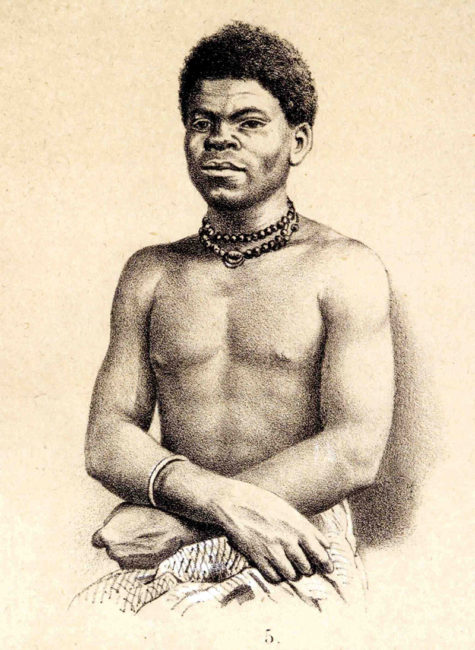

A number of debilitating scandals meant that the government could no longer hide the deep flaws within this system: recruiting in areas where slavery was not prohibited and allowing captives to be bought and sold at considerable profit was tantamount to condoning a new form of trafficking. Seen in this light, the system of indentured workers from Africa clearly failed in the very principle of its original goal, further suffering from the onslaught of vitriol from the British authorities in their efforts to accuse France of perpetuating the slave trade. Indentured workers from Africa were bought and then freed as purely a matter of form, receiving neither consideration nor assistance once in the colony. Their original status as slaves in their own country and lack of protection from a foreign government distinguished them from their Indian counterparts. Although they were subject to colonial legislation which covered all of the colony’s workers, they were nevertheless victims of greater discrimination and longer-term enslavement .

Abandoned in 1859 in favour of a system that was less open to criticism but subject to even greater British control, African indentured labour in Reunion Island was used as a bargaining chip to bring in vast numbers of Indians and the consequential signing of a Franco-British agreement in 1860. Thus, France preferred to recruit “Indians who are free and to whom no suspicion of slave trading can be applied, unlike for black Africans (sic) for whom, given their low social levels and their notorious conditions as a minority, it is easier for English philanthropists to describe as victims of a veritable slave trade ” . Yet for the next two decades, colonists in Reunion Island would make relentless requests to reopen this source of immigration, preferring by far the qualities of the African worker to those of his Indian counterpart. These planters would base their request on a glaring paradox: they claimed that the resumption of this activity would be in the name of humanity and in the very interest of the Africans concerned.

At the end of the century, the denunciation of the Franco-British agreement by the English government in 1881 put a definitive end to the recruitment of workers of Indian origin, once again plunging local planters into a renewed dilemma. Turning to desperate means, Reunionese planters revived the idea (one they had never totally given up on) of an official resumption of African immigration. The abolition of slavery in the Portuguese colonies in 1869 and the closure of the Zanzibar slave market in 1873 inevitably led to new forms of recruitment and the resumption of African immigration was conditional on the implementation of a Franco-Portuguese agreement signed in 1887. Limited to a few ports in Mozambique, this resumption sought to recruit volunteers who were looking to earn money. Without completely eradicating systematic abuse, this new legislation and monitoring from Portuguese authorities served to legalize an immigration which, until then, had been nothing more than the slave trade in disguise. With their status as free men, these indentured workers did not settle in the colony and a large majority demanded to be repatriated. And given their small numbers, the system of mass immigration seemed to gradually swallow them up and assimilate them as mere immigrant workers. Between 1887 and the beginning of the First World War, only 3,000 of them came to Reunion Island. In 1887, while all the hopes of the planters were based on the resumption of African immigration, this system of free labour would prove insufficient to meet labour needs and would gradually be abandoned at the beginning of the 20th century.

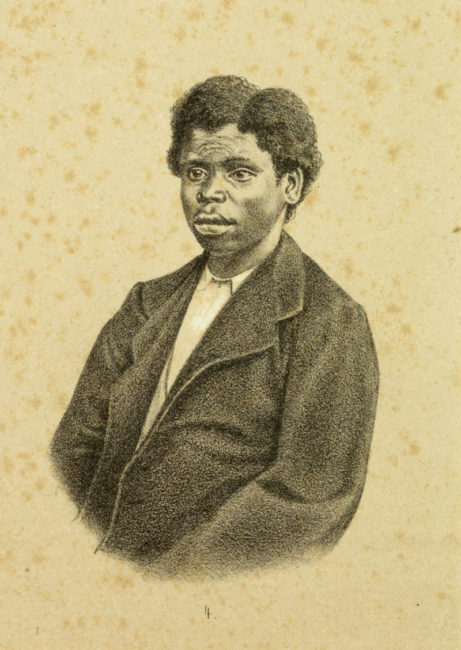

The system of indentured labour from Africa eventually revived, prolonged and maintained a form of domination that had considerable and lasting consequences. Stereotypes and assimilation to the status of a slave (i.e. the status of a non-free person) played a fundamental role in building up prejudices. Connected to a specific colonial legislation and to their origins, their status as indentured workers from Africa would hugely affect their social integration. Boundaries between indentured workers and slaves were all the more permeable and fluctuating for those indentured workers from Africa, as collective memory continued to assimilate them as bona fide slaves.

Nowadays, the descendants of indentured workers from Africa have not formed any social group in their own right, as is the case with the descendants of indentured Indians ‘Malbars’. On the contrary, they blend in with the mass of other Reunionese of African origin, descendants of slaves or recent immigrants. They are commonly referred to as ‘Cafre’ or ‘Kaf’, a term that covers all Reunionese of African origin and more broadly all those who have the ‘Cafre’ physique. Moreover, their history is still unknown to the Reunionese, or even denied in the sense that the vast majority of the island’s population believes that a ‘Cafre” can only be a descendant of slaves, only using the term ‘indentured’ for workers from Asia. The history of the African indentured labourers in Reunion Island is destined to remain a ‘silent history’ to quote historian Hubert Gerbeau. It is therefore vital to give these descendants of African indentured workers a past that is their own, a history that is distinct (even if it bears the stigma) from the slave trade and slavery and fully included in the story of indentured labour around the world.

• CAMPBELL G. R., “Le commerce d’esclaves et la question d’une diaspora africaine dans le monde de l’océan Indien ” in Cahiers des Anneaux de la Mémoire, De l’Afrique à l’extrême orient, n°9, Edition des Anneaux de la Mémoire, Nantes, 2006.

• CAPELA J., MEIDEIROS E., “La traite au départ du Mozambique vers les îles françaises de l’Océan Indien, 1720-1904, Chapitre III : les Libres engagés, 1854-1904” in Slavery in South West Indian Ocean, Moka, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, 1989, pp. 247-309.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., De l’Afrique orientale à l’océan Indien occidental, Histoire des engagés africains à La Réunion au XIXe siècle, PhD thesis in contemporary history under the supervision of Professor Jacques Weber, University of Nantes, 2010.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., Sources et méthodes pour une histoire des engagés africains à La Réunion, de la veille de l’abolition de l’esclavage à la fin du XIXe siècle, D.E.A. dissertation, under the supervision of Jacques WEBER, University of Nantes, 2002.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., “Engagés africains et engagés indiens à La Réunion au XIXème siècle, une histoire commune… “, in Le travail colonial. Engagés et autres mans-d’œuvre migrating in the empires 1850-1950, under the supervision of Issiaka Mande and Eric Guerassimoff, Editions Riveneuve, 2016, pp. 197-229.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., “La reprise de l’immigration africaine à La Réunion à la fin du XIXème siècle : de la traite déguisée à l’engagement de travail libre “, French Colonial History, Michigan States University Press, 2016.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., “L’engagisme africain à La Réunion, une traite déguisée, 1848-1859? ” in Couleurs, esclavages, libérations coloniales, 1804-1860, éditions Les Perséides, Paris, September 2013, pp. 153-178.

• CHAILLOU-ATROUS V., “Les engagés africains à La Réunion : entre ruptures et résurgences d’un système condamné”, in Les traites négrières coloniales, Histoire d’un crime, Editions Cercle d’Art, Paris 2009, pp. 127-139.

• CHEREL J., “Esclavage, traite cachée et mémoire à Mayotte”, in Cahiers des Anneaux de la Mémoire, De l’Afrique à l’extrême orient, n°9, Edition des Anneaux de la Mémoire, Nantes, 2006, pp. 293-312.

• DUBOIS Colette, ‘Réunion-Afrique orientale et mer Rouge: un mariage contrarié, 1814-1870’, in Histoires d’Outre-Mer, t.2, 1992, pp. 423-446.

• DUFFY J., A question of slavery, Labour policies in Portuguese Africa and the British protest (1850-1920), Londres, Oxford university press, 1967.

• FIERAIN J., “Nantes et La Réunion au temps du Second Empire. Les origines de la maison d’armement Henri Polo et Cie (1856-1861)” in Enquêtes et Documents, I, University of Nantes, Research Centre for French Atlantic History, 1971, pp. 283-367.

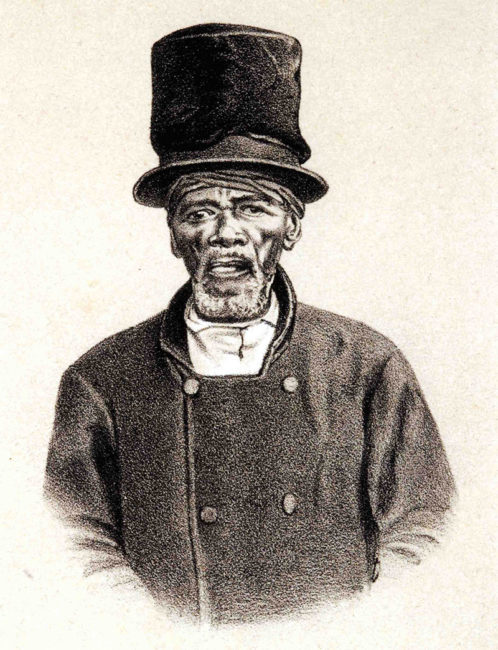

• FUMA S., (presentation of), Chambre noire, Chants obscurs. Photographies anthropométriques de Désiré Charnay : Types de La Réunion, 1863, exhibition catalogue, General Council of Reunion, 1994.

• FUMA S., Histoire d’un peuple, La Réunion 1848-1900, CNH editions, 1994.

• FUMA S., Mutations sociales et économiques dans une île à sucre : La Réunion au XIXesiècle, PhD thesis under the supervision of J.L MIEGE, University of Aix-en-Provence, September 1987.

• LY-TIO-FANE Huguette, “Aperçu d’une immigration forcée : l’importation d’africains libérés, aux Mascareignes et aux Seychelles, 1840-1880”, Etudes et Documents, IHPOM, Aix-en-Provence, n° 12, 1980, pp. 73-84.

• MAUGAT E., “La révolte des Noirs du ” Regina Caeli ” (1857) ” in Cahiers des Salorges, Nantes, n°18, 1968, not paginated.

• MONNIER J-E, Esclaves de la canne à sucre: engagés et planters à Nossi-Bé, Madagascar 1850-1880, L’Harmattan, 2006.

• RENAULT François, Libération d’esclaves et nouvelle servitude, Abidjan, Les nouvelles éditions africaines, 1976.

• WEBER J., “Les conventions franco-britanniques de 1860-1861 sur l’émigration indienne (Pressions en Afrique)”, Cahiers des Anneaux de la Mémoire, n°2, Esclavage et engagementisme dans l’océan Indien, La traite atlantique, Nantes, édition des Anneaux de la Mémoire, 2000, pp. 150-156.