They provide the people of Reunion with a way to express their identity through both music and dance. In Reunion, these forms have become entities in their own right, but are also found across six different Indian Ocean islands, and in each version, the melting-pot style comes shining through each time. Their musical aesthetics, choreography and different instruments are all the result of successive cultural and social blends.

The fusion of Afro-Malagasy influences gave rise to maloya, while the creolisation of Afro-Malagasy and European legacies gave rise to séga.

Throughout its history, maloya has undergone notable transformations, shifting across a variety of musical realities, going from the ‘danse des Noirs’, ‘danse des Nègres’, ‘danse des Cafres’, to ‘t’siega’, ‘tsiega’, ‘tchiega’, ‘tchéga’, ‘chéga’, ‘shéga’, ‘ségah’ and finally séga at the end of the 19th and even the beginning of the 20th century. After that, this old form of music and dance gave rise to a second, more harmonized version, which was more popular and based on a blend of traditional European ballroom music and local rhythms of Afro-Malagasy origins. This was séga (whose older homographic term for the original musical genre was superseded by the word maloya). Since then, Reunion has been home to two main traditional musical and choreographic aesthetics, that of maloya (a mix of Afro-Malagasy influences) and séga (a creole version of Afro-Malagasy and European legacies).

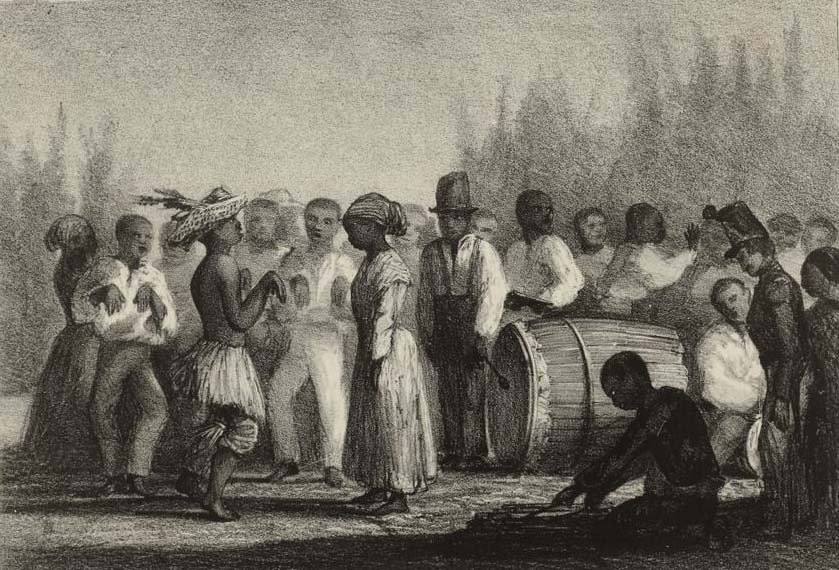

Following their deportation to the Indian Ocean, Malagasy and African slaves continued to respect certain rites (both sacred and non-religious) and musical traditions, which ended up becoming creolised. Essentially rhythmic music made from percussion instruments and sometimes a musical bow and a lamellophone, the primitive form of séga was thus played during ‘kabaré’, ‘Malagasy’ or ‘Kaf’ services to honour their ancestors and during the ‘Black’ or ‘slave’ dance (which finally became known as ‘kabar’) for more festive gatherings. From 1921, the original word ‘séga’ was replaced by ‘maloya ’ , a Malagasy word meaning uneasiness, sadness and pain.

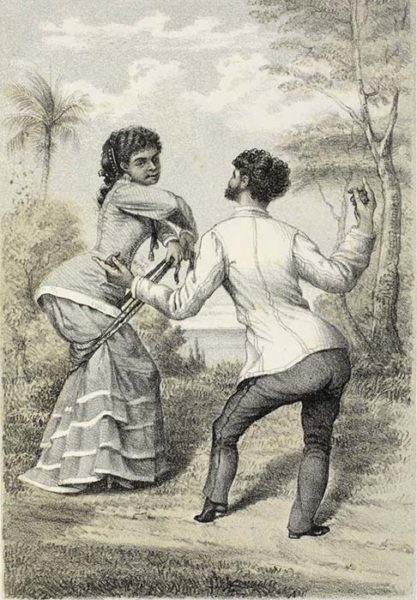

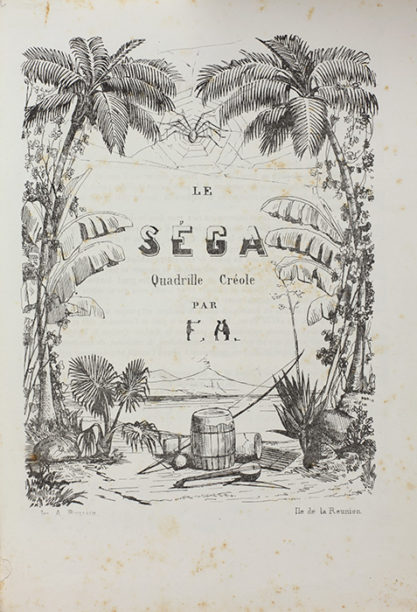

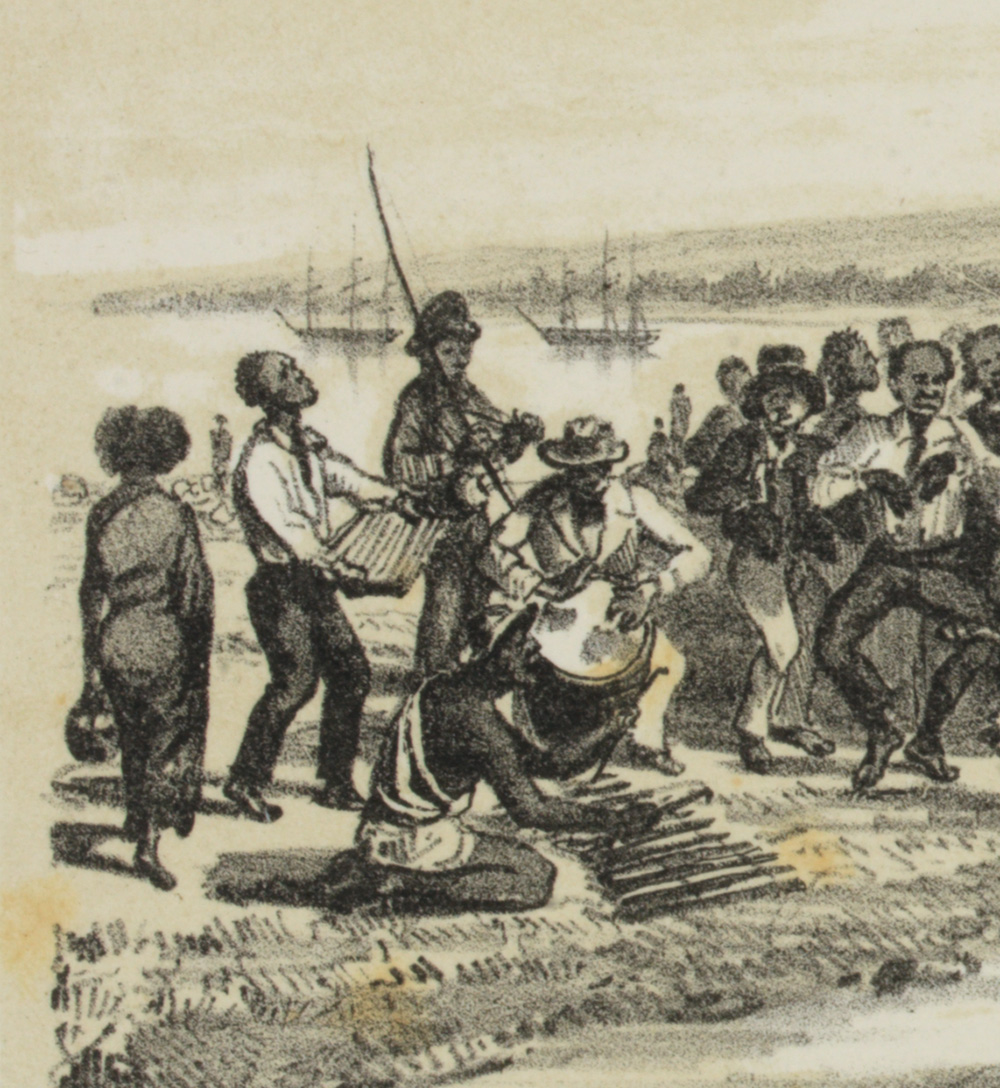

In the mid-19th century, the quadrille and European ballroom dances (contra-dances, waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, Highland, etc…), were brought into Reunion by the bourgeoisie, mainly composed of soldiers from different strata of the colonising population. Often performed on the violin and the banjo by minstrels and musicians known as ‘jouars’, these dances (and more particularly the quadrilles) became creolised, first in the chic salons of the local bourgeoisie and then in rural folk dances.

The end of the 19th century saw local productions of “quadrilles sur des airs créoles des Nègres en respectant scrupuleusement le caractère exotique ” (“quadrilles with Creole Negro tunes that keenly respect their exotic nature”). Soon, Creole words were added to these traditionally instrumental tunes, and thus contemporary séga or Creole ‘ditties’ were born. It soon firmly established itself in Reunion’s musical landscape, alongside fashionable ballroom dances, classical and military music, European odes and songs, but also the ritual and festive maloya.

Popular at every ceremony and festivity, the dances which are specific to maloya and séga music are also the result of a blend of rhythms brought in by disparate and uprooted communities: during the time of slavery for the clandestine maloya dance, and during the 20th century for that of sega, thanks to the melodic and choreographic influences of the European quadrille.

The Maloya dance was the social glue holding together a community (at the beginning for slaves and then for Creoles), whilst also being a fusion of physical expressions from different ethnic groups. Similarities with Bantu and Mozambican dances are clear: feet-stamping, opening the arms and swaying the hips, and the fact that dancers don’t touch each other. Some masters did not allow their slaves to have any form of entertainment themselves and for this reason many gatherings were clandestine, taking place in the shadows until slavery was abolished. From then on, maloya continued to be popular among the free population, eager to keep their deeply rooted customs alive, but the authorities and the Catholic clergy generally saw it as a potential threat to the established order. In spite of the attempt to ‘ban’ it (a decree by Prefect Perreau-Pradier in 1956), maloya continued, mainly through ancestral worship and celebrations of the abolition of slavery. From 1976, this music and dance was hijacked somewhat for political purposes by the Reunionese Communist Party, becoming the embodiment of a cultural Creole resistance to French culture. Since 1981, thanks to Jack Lang’s national cultural policy in favour of the recognition of regional identities, maloya was officially authorised once again. Finally, since 2009, this form of cultural expression has been listed by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Thanks to support through cultural policies of local institutions, maloya has never been so popular across the performing arts network (local, national and international stages, recordings etc.). And for more than thirty years, musical fusions with other world genres have been ongoing (jazz, rock, pop, folk, reggae, rap, raga and dance-hall). In comparison, séga has lost a little popularity during the 21st century, its image sometimes labelled as outdated or folkloric (in the pejorative sense of the term), even though it is a key part of contemporary music and a source of the island’s musical creativity

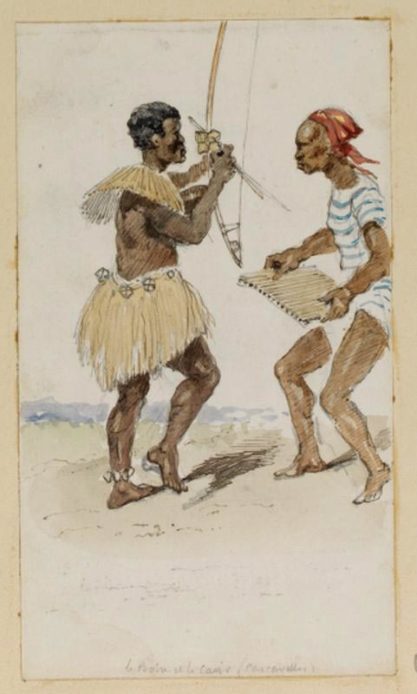

Originally from Africa where it is known as chiquisti or kaembe in the southern provinces of Mozambique and as kayamba in Kenya and Zanzibar, this idiophone became the raloba in Madagascar and the mkayamba in Anjouan or Mayotte.

Also known in Reunion Island as cavir or kavia, before becoming caïambre, caïamb, kayanm, this instrument is the equivalent of the maravanne in Mauritius. In Malagasy, the the word ‘kayanm’ means ‘that which rings’, but in Madagascar they also have another idiophone called the ‘kahiamba’ (which is a tubular idiophone). It seems that it first appeared in Reunion Island relatively recently, given that it wasn’t seen in any engravings or documents until 1848.

This idiophone is made of a rectangular resonance box (about fifty centimetres long by thirty centimetres wide and three centimetres thick) made from a wooden frame covered on both sides with cane flower shafts tied or nailed together. Inside are what makes the characteristic rattle sound, usually tropical vegetable seeds (saffron, job’s tears, conflor...). Players hold it lengthwise in the palm of their hands and, while shaking the instrument from left to right, they strike the resonance box with both thumbs. However, one of Antoine Roussin’s lithographs from 1860 (“Le séga, danse des Noirs, le dimanche, au bord de la mer”) shows a musician who, like in Mauritius, holds the instrument widthwise.

The Kayamb is mainly played for rhythmic purposes within traditional maloya groups. It can also be found in many groups who are part of the world music scene.

Similar to the Brazilian berimbao, this one-string cordophone with resonator can be found on various islands in the Indian Ocean, including Mauritius, Rodrigues (called bom), Mayotte (dzendze lava) and the Seychelles (bonm). It may have originated in Madagascar, where it is known as the jejilava, and, like many traditional instruments, spread throughout the region by the immigrant slave population from Madagascar. That said, it is also found in Mozambique, where this type of musical bow with resonator exists under the names of chitende, n’thundao or chiqueane (south of Rio Save), and chimatende (in the province of Sofala).

According to the ethnomusicologist Jean-Pierre La Selve , it is possible that the vernacular name ‘bob’ (formerly bobre), specific to Reunion Island today, could have come from Europe: “The musical bow is reminiscent of an instrument often depicted in Flemish painting, the ‘bumbass’, a single-stringed instrument whose resonator is a dried pig’s bladder, and which was used in Northern Europe as an instrument during carnivals. It is therefore possible that Flemish sailors (…) may have introduced this name which, when removing the last syllable, changes from ‘bumbass’ to ‘bomb’, then from there to simply ‘bom’”.Also, iconography of the period shows notable similarities between the resonators of European instruments and the first Reunionese models made of bladders.

Finding the origins of the bobre (now bob) is not easy: as the result of syncretism, its construction and usage have both evolved since it arrived on the island. The animal bladder used as an amplifier is now a hollowed-out gourd with the top third cut off, connected to a tin can. Formerly plant-based, the rope is now a steel wire, an electricity cable or a bicycle brake cable. To strike it, the original branch (curved taut using horsehair) has been replaced by a thirty-centimetre long batavek, also called tikouti (or failing that, a coin). The kaskavel rattle, traditionally held in the musician’s right hand (when right-handed) was made of a braided vegetable pouch of seeds (saffron, job’s tears…), has become rare today.

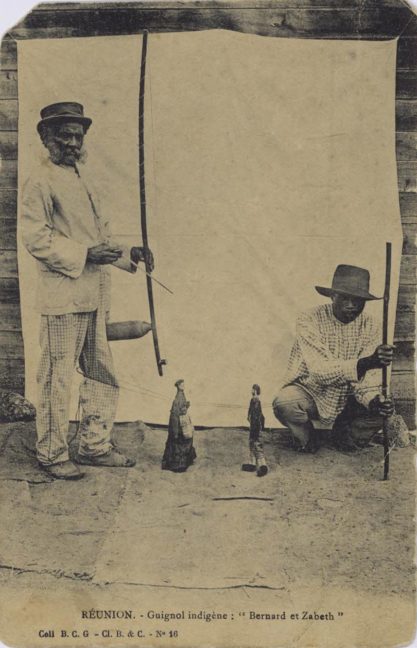

Musicians strike the wire, holding the gourd either to their chest or stomach, as the desired tuning depends on the height of the resonator. Holding the bow at the resonator, the player’s fingers can also influence the sound by the tension of the string. Played for melodic-rhythmic purposes as a soloist for laments and maloya pléré, or as part of the instrumental repertoire for festive maloya (formerly known as danse des Noirs), the bobre was also the used by travelling puppeteers until the beginning of the 20th century.

Part of the membranophone family, the roulèr (formerly rouleur) is a tubular drum in the shape of a barrel, and specific to Reunion Island. Unlike the other drums in the region, which are essentially frame drums, this is the only one which rests horizontally on a base called a santyé. It could be a descendant of the conical drum (vouve or long drum) which has since disappeared but has been observed in old Reunionese iconography, or even related to the atabaque from Madagascar (which has survived in the Seychelles under the name of séga drum). It is clear that the roulér (or that percussion that inspired it) was the result of a blend of styles that arose during the time of slavery, based on African influences. By way of illustration, the same type of drum (called the ka) can be found in Guadeloupe, a former French colony populated by descendants of African slaves. It is therefore quite likely that, following their arrival on the island, Reunionese slaves made drums that were somewhat different from the ones they were used to handling, as the materials available to them were no longer the same. For this reason, we have not found any drums identical to the roulèr on the African continent from which it originated.

The vernacular name ‘rouleur’ comes either from the movement of the musician’s hands or from the wiggle of the hips typical of the danse des Noirs (the ancestor of maloya). This instrument, which provides the rhythmic basis for maloya, is traditionally made from a barrel truncated at both ends. One end is covered with a tanned and studded ox skin. Nowadays, since these barrels are no longer imported to the island, instrument makers have started making them from local woods such as champac. In order to make tuning easier, without having to heat the skin to soften it, they also tend to tie the membrane using a system of ropes.

Played with bare hands, the roulèr was struck with a mallet in the 19th century, as ancient documents testify. In this case, musicians did not straddle the instrument, whereas today this position allows them to lean one leg against the skin so as to modify the tension of the skin and obtain a variation in timbre and tonality.

Originating from Mozambique, the timba (ancestor of the timbila or mbila), which totally disappeared from the range of traditional maloya instruments at the beginning of the 20th century, was originally a xylophone made of wooden keys of different sizes (thus creating a scale), set on hollowed gourds serving as resonance boxes. This instrument is featured in a number of 19th century iconographies from Reunion Island, and is likely to be a descendant of the free-standing xylophone from Madagascar. In both Madagascar and Reunion, the lamellophone does not require a gourd. However, while in Reunion it rests on the ground or in a pit, in Madagascar the instrument is placed on the musician’s legs. Thus, we can conclude that the timba is the result of a blend of Mozambican and Malagasy influences. Although of totally different instrumental styles, the pikèr is an idiophone which is also struck by two wooden sticks, which first arrived to replace the timba during the 20th century. Similar to the tsipetrika in Madagascar, the pikèr consists of a length of bamboo (about sixty centimetres long and about fifteen centimetres in diameter), resting horizontally either on a stand or on the ground. Its vernacular name seems to refer to the playing technique of the musician who strikes the instrument rhythmically. At the same time, the word sati (an Indian word to describe a small hemispherical Tamil drum) is also used for the same type of percussion, whose body is replaced by a sheet metal container, a crushed can or any other metal container that can serve as a resonator. Sati is therefore a derivative of the pikèr, which has itself displaced the timba. Depending on the desired timbre resulting from the material across the cavity being struck, either pikèr (plant-based) or sati (metallic) are both part of maloya‘s range of instruments.

Originally from Europe, this percussion idiophone, whose name comes from its shape, was brought into Reunion in the second half of the 19th century, which is relatively late compared to other maloya instruments. While most triangles are made industrially today, many of them were still handmade until the 1970s, modelled from heavy steel rods used as reinforcement in building construction. Fashionable in the 20th century, it is nowadays mainly replaced by the pikèr or sati.

The first European instruments (piano, mandolin, banjo, guitar, violin, clarinet, flute, accordion…) which were used during the earliest days of the Europeanised version of séga date back to the 19th century. These instruments were in fact mainly imported by boat and by the young bourgeois who, after studying in European military schools, came to join their families on the island. They were used to entertain high society during bourgeois balls, before becoming widespread (Creole quadrilles, waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, Highland, ségas…).

Later, during the 20th century and particularly during the golden age of séga (1950-1980), instruments such as the drums, bass and electric guitar appeared and are still an integral part of the musical repertoire today.