From the start of colonisation, these two issues were to become present, explicitly or implicitly, in Reunionese literature. We can even suggest that Reunionese literature was born through a questioning and analysis of these two topics and issues, similarly to, and perhaps in imitation of, Mauritian literature, more specifically Paul et Virginie, the work by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1788), et above all his work Voyage à l’Isle de France, à l’Isle Bourbon, au cap de Bonne-Espérance (Journey to the Ilse de France, Bourbon island and the Cape of Good Hope) (1773).

In January 1775, Évariste de Parny wrote to Bertin. After expressing to his friend his admiration for the beauty of the landscapes, the excellent quality of the air and the fruits growing there, as well as the gentle way of life, he insists on the the monotony that reigns, the permanent boredom. He gives a negative description of the Creole society, based on laziness, corrupt morals, deceit and jealousy, as well as a long description of the negative aspects of slavery.

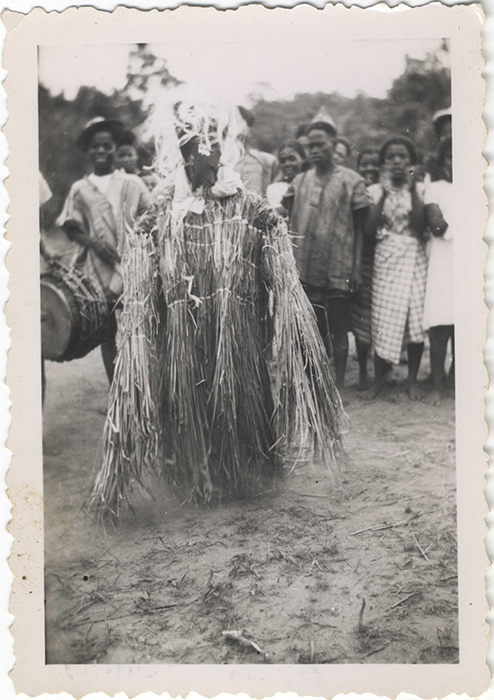

The most important of his texts, Chansons madécasses (Songs of Madagascar) (1787), evokes those enslaved and, implicitly, maroons, giving them a voice and a poetic representation. These songs were written on the basis of forms of Madagascan poetic language, from what he heard concerning the family environment. The original authors or those inspiring the text, its prosody, rhetoric, rhythm and musicality, were Madagascans enslaved on Bourbon island. An anti-colonialist and anti-slavery poem, denouncing the colonial predatory society, the slave trade and slavery, Les Chansons madécasses are the first example of prose poems in French literature.

Slavery and forms of resistance thus form the basis of Reunionese literature, both in French and in Creole. In 1828, Louis-Émile Héry published his Fables créoles dédiées aux dames de l’Isle Bourbon (Creole fables dedicated to the ladies of Bourbon island). In 1821, in Mauritius, François Chrestien had published Essais d’un bobre africain (Essays on an African bobre). In the same way as the title of the prose poem by Parny, which placed the text under the influence of voices from Madagascar, Chrestien’s text placed his under that of the bobre, an African musical instrument. It is notable that the improved third edition of Louis Héry’s work is entitled Nouvelles esquisses africaines (New African sketches).

The presence and the voices of the enslaved create the text, notably in ‘Le meunier, son fils et l’âne’ (The miller, his son and the donkey). While the story is that same as the one by La Fontaine, the setting, the linguistic, discursive and anthropological contexts are clearly those of the plantation environment on Bourbon island and above all, the enslaved are the actors of this linguistic and verbal theatre.

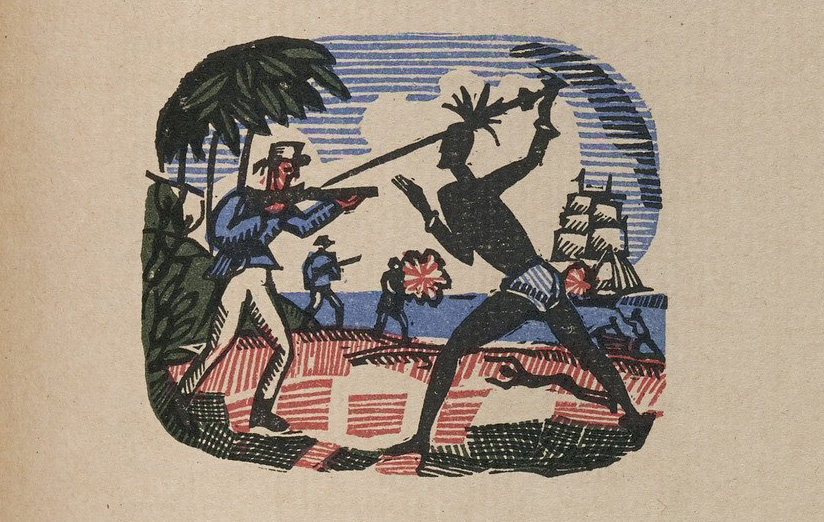

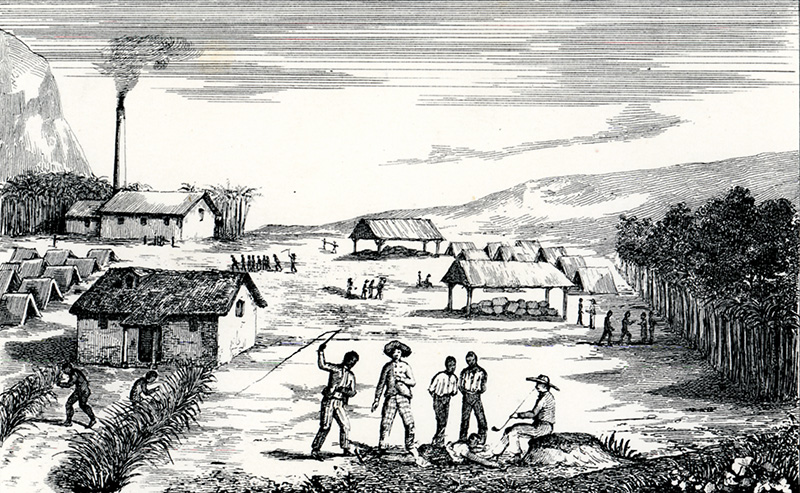

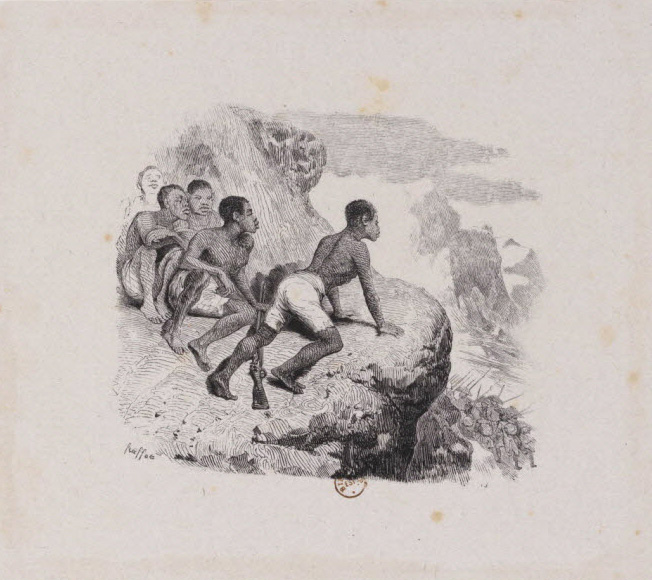

The birth of the Reunionese novel is also linked to this universe. The first of these, Louis-Timagène Houat’s, Les Marrons (Fugitive slaves) (1844), depicts the constitutive and systemic violence of the plantation system, explicitly a work camp that is a space of terror, humiliation, loss of humanity, brutality and torture. But it also depicts racial mixing. The main characters – as well as the others – are two maroons (escaped slaves), Frême, a Black and Marie, his white companion. The novel closes on a general slave rebellion and the collective decision to leave and settle in the maroon camp.

In 1847, Leconte de Lisle published Sacatove, the story of an escaped slave who, in love with Marie, the daughter of his former master, carries her away. The character, inspired by Bug-Jargal (Victor Hugo, 1826), corresponds to what Léon-François Hoffmann defined as being the figure of the “Romantic Negro”. . Like Bug-Jargal, Sacatove is depicted as a chivalrous figure with noble feelings, hopelessly in love with Marie, his master’s daughter. Like the latter, Sacatove is killed by the masters, but there the similarities end. Indeed, Bug-Jargal is shot by the army leading the fight against the insurgents, whereas Sacatove, in despair before his unrequited love for Marie, comes back to give himself in and is killed by Marie’s brother. However, the novel ends on an open note. When Marie returns to her father’s estate, the latter rushes to marry her off and she gives birth to a child whose skin, the narrator tells us, is as white as any other, suggesting that it is actually Sacatove who has fathered the child. While Hugo’s text clearly represents the separation between the races, Leconte de Lisle’s suggests racial mixing as a utopia for abolishing slavery.

In 1848 Eugène Dayot published “Bourbon pittoresque” in Le courrier de Saint-Paul. The topic of this unfinished novel is long-term maroonage in the 18th century, seen through the eyes of the slave-hunters. The general tone of the work is what has been referred to as “Haitian Gothic” , that is to say a derogatory and negative vision of the maroons. However, there is a thread running through all these texts, that of of the systemic melancholy stance of the white characters in the text. Within the context of slavery in the plantation structure, logically, this notion will then be present throughout the Reunionese colonial novel.

Auguste Lacaussade, a Mulatto like Houat, published the collection Poèmes et Paysages in 1862, coming back to the topic of maroons. Already in Les Salaziennes (1839), the fifth text in the collection, “Le lac des gouyaviers et le piton d’Anchaine” (The cherry guava lake and the peak of Anchaine) evokes the figure of the fugitive slave Anchaing, praising resistance and liberty, whatever the price to be paid.

Poem XVIII of Poèmes et Paysages, “une voix lointaine” (a distant voice), includes a violent attack on the system of slavery and against submissiveness, opposing the stunning beauty of the island’s natural environment and the situation of those enslaved.

In poem LXXIX (79), “Le Bengali”, Lacaussade depicts a lonely character in the darkness, whose melancholy chant evokes both his situation of servitude and the period when he lived in freedom in his native land.

In 1958, continuing the trend of the colonial novel, Claire Bosse published Colonisation de l’île Bourbon ou l’idéal amour (Colonisation of Bourbon island or ideal of love), which is presented as being the positive version, seen from the viewpoint of the white masters, of the novel by Dayot published a century earlier. The narrative refers back to “Gothic” characteristics, using such expressions as “absolus sauvages” (absolute savages) (p. 8), “hordes barbares” (barbaric hoards) (p. 9), “loups avides” (hungry wolves) (p. 9). By contract, the narrator presents “the peaceful happy lives of the civilised inhabitants living on the coast,” enjoying “the island’s eternal Spring. The text, reflecting the long war between two racial and class utopias, that of the sovereignty of the maroons in the mountains and that of the masters on the coast, proposes to establish happiness for the whites on the basis of a genocide. Total elimination of maroons is presented as being the necessary condition for “unobstructed happiness”. The condition for establishing Eden is the massacre of all maroons. This clearly demonstrates the extent to which the topics of slavery and maroonage in literature are always represented through the prism of war, a never-ending conflict.

The novels of Marius-Ary Leblond are based on poetry that aims to be naturalistic and anti-exotic. While slavery or maroonage are absent from their novels and short stories, the shadow of these is present. The novel most strongly marked by this presence/absence is Ulysse Cafre. Histoire dorée d’un Noir, (Black Ulysses. The Golden History of a Black) (1924). The topics of wandering, filiation, naming of places and language bring to the surface the voices, presence and actions of the slaves and maroons. Ulysse, a cook working for the narrator’s family, one day decides to leave the latter to go in search of his long-lost son. During his wanderings around the island, Ulysse encounters a number of persons, giving an account of his genealogy and parentage to one of them and explaining the origin of Abel, the name given to his father, who was a slave.

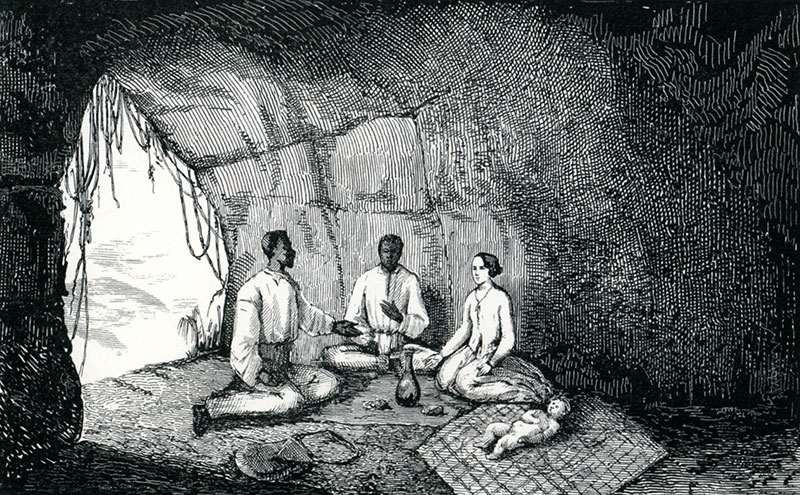

The passage shows how the naming of slaves deprived them of their original names and their presence in the lineage, uprooting them and branding them with the master’s mark, a sort of symbolic repetition of being branded as property on their body. But Ulysse’s discourse about his father’s name brings to the surface that given by the lineage, linked to the original space and remaining in the unconscious collective memory of the descendants. The name, Laouallé, appearing in his memory and his dreams, haunts Ulysse’s narrative and transforms the very texture of the novel. In the colonial novel as a whole, the apparent absence of narrative around slavery and maroonage to a certain extent places this narrative at the origin of any discourse aimed at depicting the contemporary Reunionese space and the process of its construction. The wanderings of Ulysse, despite the narrative discourse apparently reflecting assimilation and integration – to a secondary role – of the descendant of the slave with the values of white Christian civilisation, turn out to be a discourse on contemporary maroonage illustrated by the discovery of hidden, secret, buried places and practices, spaces of therapy and sorcery, expressing praise for an ecological occupation and organisation of the world, actually the legacy of the way of life of the maroon slaves.

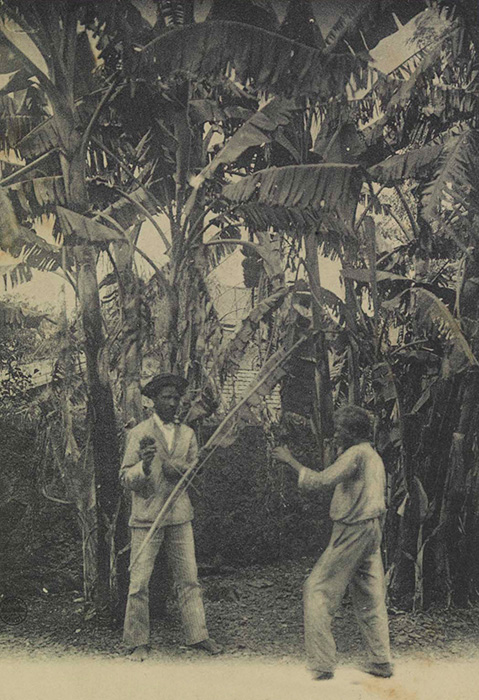

Private collection of Arnaud Bazin (1977-), inv. 1 P8.32

The novel presents three women, Sylvie de Kérouët and the enslaved Kalla who is totally devoted to her and who will end up killed by Zélindor, chief of the maroons, and Eudora de Nadal, Sylvie’s descendant, but whose filiation is unclear . Through the diary kept by her ancestor, Eudora learns of the interwoven stories of Sylvie’s life and that of Kalla, who paid with her life for her devotion to her mistress, and whose body was never found. The absence of any tomb for her has turned Kalla into a wandering soul, Granmérkal, who appears in order to announce to the De Nadal family the imminent death a member of their family or warn them of a possible danger. Eudora, who believes she is the reincarnation of her ancestor, becomes prey to melancholy. In order to be healed and gain legitimacy in the space of Mahavel, in harmony with the place and its history, she has to find the remains of Kalla and give her a tomb, which she does at the end of the novel.

Situated between the colonial and the post-colonial novel, the narrative is ambiguous: setting up Kalla’s tomb consists not so much in giving her a space as providing peace for Eudora and her descendants, even though bringing up the remains of Kalla contributes to bringing up a different story or the History of the others in memory, discourse and text.

This History will be explicitly treated by the poetic texts written during the second half of the 20th century.

The last “premonitory” line of the collection Zamal by Jean Albany (1951), is: “Bobre, bobre, instrument de musique créole” (Bobre, bobre, Creole musical instrument). In the colonial novel, ‘Creole’ was synonymous with “white”, whereas for Albany it is inclusive. From then on, the bobre becomes the symbol of Reunion culture.

Bal Indigo, published in Creole (1976), is more explicit. “Commandeur” evokes the violence and torture inflicted on slaves and opens the perspective of putting an end to the system of slavery thanks to a general rebellion led by escaped slaves. Significantly, in the second to last line, the partitive article preceding the words ‘milk’ and ‘honey’ is written applying the pronunciation ascribed to slaves of African origin that in an article written in 1884 the historian of Creole Eugène Volcy Focard qualifies as ‘Mozambican Creole’.

“Monte Chemin Cormoran” a twenty-page text, evokes the figure of Mme Desbassayns, the appalling situation of her slaves, with maroonage as the way to destroy the system.

Tienbo le rein et Beaux visages cafrines sous la lampe (Hold your head up high and beautiful Black faces in the lamplight) by Alain Lorraine (1975) places the history of Reunion under the sign of exile, migration and deportation. Enslavement and maroonage were the foundations the island was built on. It is no accident that the opening poem of the collection is entitled ‘Mozambique’ and insists on the relationship between memory and resistance.

The important text treating the saga of maroonage, however, is Boris Gamaleya’s Vali pour une reine morte (Vali for a dead queen) (1973). This long theatrical poem presents the gestures of maroons through the characters of Rahariane and Cimendef, whose memory is to be kept alive in order to declare and inhabit an island different from that historically created through the slave-trade, slavery and colonialism. Through the relationship between Rahariane and Cimendef, as well as the conflict between Cimendef and the slave-hunter Mussard, or Ombline Desbassyns, the text sheds light on the contradiction between the fact of inhabiting an island with links to slave estates and colonialism, and the fact it can be inhabited. In view of the situation, the island is de facto uninhabitable. It is thus necessary to live like a maroon and fully embrace human presence and the presence of other beings, plants and spirits. This is why, in Gamaleya’s poetry as a whole, the mountain areas of the island, the peaks, crests and mountain slopes have an important role to play. They are the very essence of maroonage, difficult to access by the masters of the estates and the slave-hunters, but above all a space of free sovereignty embracing life, both human and otherwise. For Gamaleya, maroonage is the opposite of the plantation. The space of maroonage links words and bodies to the mountains, trees and plants, reconstructing the links that disconnect because they reconnect. Nature is at the centre of Gamaleya’s writing because it is rebellious: it is the memory of maroonage that enables the interweaving of temporalities, and the infinite renewal in history of maroonage, of the liberty of tongues, languages, discourse, voices and subjects that are no longer locked within frozen identities.

Photographic collection of Jean Legros (1920-2004), inv. 5P3.JL.105