While the Indian and Chinese communities benefited from a degree of tolerance as regards the practice of their religious beliefs, their ‘artistic’ expression was not recognised or given any legitimate status. The dominant intellectual discourse was at the service of the French powers and the ‘veranda civilisation’, that is to say the large landowners incarnating the imperialist ambitions of mainland France . Only artistic objects reflecting the traditions of the dominant culture came to be considered as belonging to the history of the visual arts. To quote C.A. Célius, the fact of considering the slave as an inferior and dehumanised being “implied negating his capacity to create and obscuring any creative practices … A being with no notion of ‘art’ is one of the features of the figure of the slave constructed by the masters. This image profoundly permeated the history of art and aesthetics” . The collective heritage of Reunionese society thus retains few objects of artistic creation or religious worship produced by the enslaved members of the community. When dealing with the the issue of the memory of slavery and the slave trade, contemporary artists are faced with a double void: that of words and that of traces.

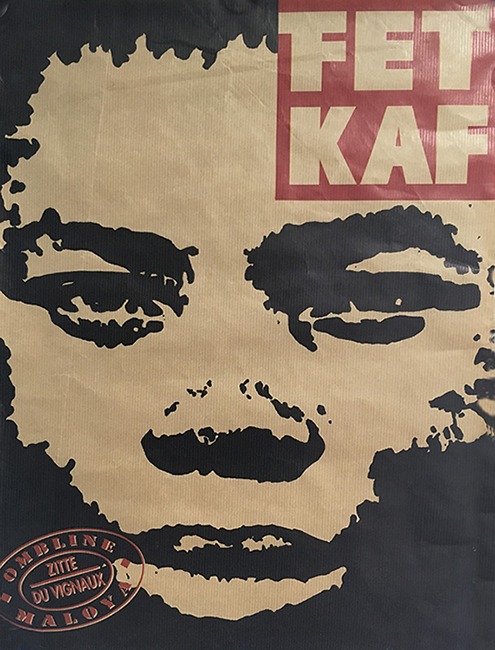

‘Mémwar: couler Kréol’ (Memory, Creole colour), ‘Les arts déchaînés’ (The arts unshackled), ‘Les bouts de bois Hurlants / au fil de la mémoire’ (Screaming splinters of wood / The thread of memory), ‘L’Abolitoire’ (Machine to manufacture liberty), ’Fêt Kaf Têt Kaf Ombline Maloya’ (Celebration of blacks, heads of blacks, Ombline Maloya), ‘Kaf an tol’ (Black man in jail), ‘Chambre Noire, chants obscurs’ (Dark room, dark songs), ‘Bwadébène’ (Ebony), ‘Regards croisés sur l’esclavage’ (Crossed visions of slavery), ‘Aboli, pas aboli l’esclavage’ (Slavery: Abolished or not abolished): all works produced on commission to mark the anniversary of the abolition of slavery . These exhibitions bear witness to a true shift in attitudes that took place in the 1990s, with the organisation in the public sphere of events linked, closely or less so, to slavery: an abundance of events that highlighted even more intensely the general silence that had, up till then, reigned over this painful period of our history. This awakening was linked to the militant activity that had been operating in the private sphere since the 70s and which was able to come to light in the years to follow. The Socialist party coming to power in France and the acceptance of identity questions as part of public policy, reflecting a European context favourable to the emergence of regional languages and cultures, all led to truly vibrant cultural activity in Reunion during the 1980s and 1990s.

How have artists treated this question of memory? What forms and what artistic language are used? What aesthetic choices have been made? What political attitudes are expressed? The ethical and political dimension cannot be dissociated from the question of memory when it comes to the slave trade and slavery: it permeates all works of art treating the topic, whether by artists who have decided to place the issue at the heart of their work or artists who have integrated it into their artistic expression in a peripheral manner. There are also works that have responded to the large number of commissions requested by public bodies in the 80s to mark the successive anniversaries of the abolition of slavery. Globally, on the formal level we can note the existence of a basic artistic vocabulary recurring in such works (painting, sculpture etc.): patterns, postures, graphic figures expressing oppression and domination, but also rebellion, liberation, fugitive slaves seized like captives with their hands tied behind their backs, diagrams of the hulls of slave ships, broken chains, images of men and women standing upright, after breaking their shackles. In addition to these characteristic elements, we can note a large range of artistic practices, with multiple techniques playing an important role, as well as appropriation of vernacular practices.

Wilhiam Zitte, Jack Beng-Thi and Karl Kugel have constructed their artistic expression around these questions related to memory, resilience and reconstruction of human relations.

A self-taught artist nourished by knowledge from encyclopaedias, after a short spell in a religious seminary, Wilhiam Zitte worked as a primary school teacher. It was while teaching pupils from very underprivileged backgrounds that he started to experiment, using ‘poor’ materials (newspaper, turmeric, yoghurt, crushed earth etc.), which then became the basis of his artistic production. An activist militating for recognition of the Reunionese identity, Wilhiam Zitte produced a vast range of artistic works (paintings, sculptures, drawings, stencils in public spaces, installations in the landscape, collections of objects, texts, productions and exhibition curations), all grouped together under the general term of what he referred to as ‘arcreology’. “Clearing overgrown or little explored paths in memory of the escaped slaves” , rehabilitating the image of the black person, restoring the history of the island and that of the least visible elements of Creole culture: Wilhiam Zitte’s artistic project is eminently ethical and political, but also contains a deeply mystical and religious dimension. As an artist, he explored the archives of the island’s past, as though exploring a landscape, in search of vestiges of escaped slaves and slavery. Collecting and diverting them, he invented his own artistic language. If history had erased their traces, he would create them himself.

In the early 1990s, he unearthed a set of anthropometric photographs in the archives, taken by Désiré Charnay in 1863. These brutal and disturbing images present, in the manner of a taxonomical catalogue, ‘racial types’, simply labelled “Africans, Madagascans, mixed-race Arabs, Chinese, black Creoles”. Men, women and children, taken face on, from behind and in profile, some with chains around their ankles, stripped naked or half-naked, standing before the photographer’s lense “for the purposes of science” at the time.

In collaboration with the historian Sudel Fuma and the poet Carpanin Marimoutou, Wilhiam Zitte set up an exhibition entitled ‘Chambre noire, Chants obscurs’ (Dark room, obscure voices) to show the public these photographs, long lying forgotten at the Natural History Museum in Saint Denis. The exhibition and its accompanying publication were presented at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris and the Palais Rontaunay in Saint-Denis in 1995.

The painful but salutary encounter with these dreadful pictures was a landmark in Wilhiam Zitte’s artistic development. In the words of Jean Arrouye: “his entire aesthetic attitude stems from the choice of these images and the emblematic role the artist assigns to them.” . Applying a process of successive enlarging of the original photographs using a photocopier, he notably produced a series of portraits painted on jute sacking, entitled ‘Ombline Maloya’ : the resulting faces with their hard contrasted features were transformed through the treatment applied by the artist. Observed close up, they are unrecognisable, but if you step back, they become recomposed, as though transfigured, their gaze expressing determination, as though inhabited by a new presence. The paintings were exhibited in 1992, during the 20th December celebrations and in collaboration with Antoine du Vignaux , in the context of artistic research on the image of the black person in a highly symbolic place in Reunion: the Panon Desbassayns estate (de Villèle Historical Museum). Wilhiam Zitte proposed a series of large works entitled ‘Ombline maloya’, depicting a gallery of portraits of ancestors who, according to Jean Arrouye, took on “the value of the return of those who had been repressed” .

Wilhiam Zitte painted on open canvas, with no wooden structure or external frame: old recovered jute sacking, but also bottoms of barrels, rusty tin sheets, supports that reflect the packaging of the goods that were shipped along with the slaves. According to the artist, these materials still bear “the memory of those who were parked in the hulls of the slave ships” : in the absence of other material traces, other than the cold accounting lists drawn up by the notaries, they become allegorical witnesses.

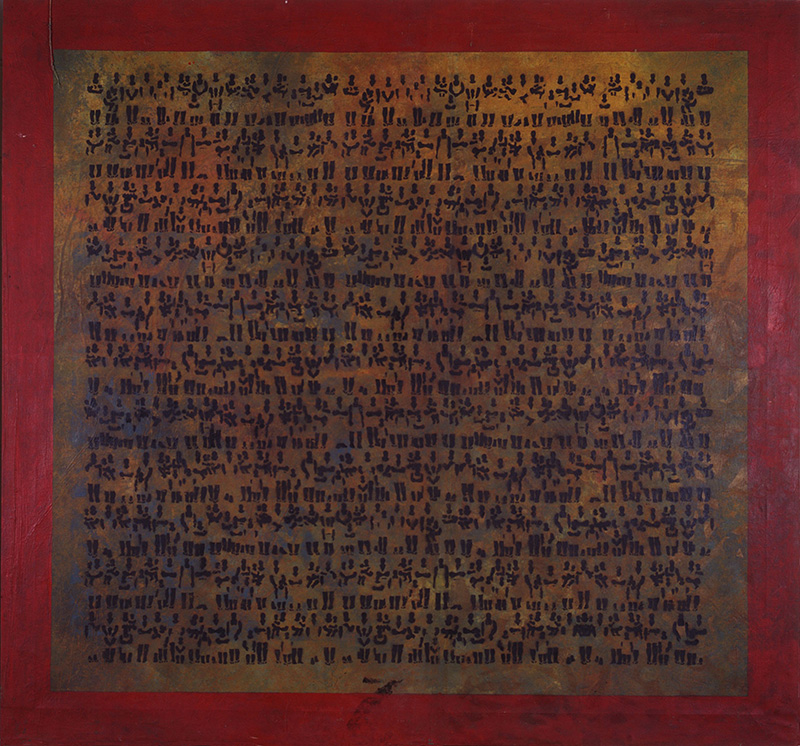

Thus he created the ‘Têt Kaf’ (African heads), which became emblematic of his work. Some were imaginary portraits, others portraits of friends or created from old photographs or more recent images from the press, quickly taking on the value of rallying signs or symbols. The artist scattered them around as stencils on walls, on the ‘black’ (tar) of the town, in the landscape, but also on newspapers, post-it notes, posters and stickers, perpetuating the process of graphic contamination with patterns of figures deviated from the diagrams of the holds of slave ships. He transformed the reclining bodies, laid down and shackled, turning them into rows of free, dancing silhouettes represented on his paintings, but also printed or embroidered on textiles (shirts, table-cloths etc.), or on object of interior design (ceramic or cut-out tin lampshades). For his series entitled ‘Domoun 97.4’ (People of 974 Reunion) and ‘Alfabé Domoun’ (People’s Alphabet), the artist took photographs of groups of men, women and mothers with children that he deviated and set up side by side, turning them into pictograms. The little black silhouettes become an alphabet, producing encrypted texts inscribed on large canvasses covered with rhythmic patterns.

The work on memory continued in 1994 with the exhibition ‘Kaf an Tol’ depicting four hundred ‘Tet Kaf’ (African heads) at the Departmental Cultural Bureau in Champ-Fleuri , alongside an extract from the genocide museum of Pnom-Penh. Four hundred ‘representations’ , which deployed their gaze through a number of exhibitions and at various sites, including the tunnel of Art’Sénik at Ravine des Sables in the year 2000, for the exhibition ‘I rogard pa’ (Not looking). Colette Pounia described it as being: “An epiphany-like road-map. A great number of heads inside a tunnel, like little lamps to enlighten our weakening memory, enabling us to confront the stifled scream (…) the trail is a maze of different itineraries, like tales to be told, links with ancestors and crossed visions” .

Wilhiam Zitte’s actions in the landscape go back a long way: as early as 1880 he went in search of the vestiges of history and occupied the natural site of Piton Rouge, a former fugitive settlement on a volcanic cone culminating at 2,397 metres. The Office National des Forêts (Forestry Department) unearthed potato plants and bones on the site. In 1990, for the bicentenary of the town council of Saint-Leu, the council commissioned Gilbert Clain to produce a series of sculptures , depicting a sleeping slave and his dream of freedom. The sculptures were set up in the former crater of Piton Rouge. This “memorial to escaped slaves” was not the sole work to inhabit this extinct volcano, overlooking the sea. Not far from the official commissioned work, Wilhiam Zitte discreetly installed his own monuments: piles of stones, pebbles set up in the trees, ‘Tèt Kaf’ (African heads) tagged on the ground and on the signs put up by the Forestry Commission. He created the vestiges of this fugitive civilisation that has left us with so few traces, creating for them tombs, the remains of their culture. Through these tangible elements, like elements of proof that are all the more vocal because they are not ostentatious, the landscape becomes inhabited, peopled and alive. The artist declared that he invented traces that history had erased: “Our lies can consolidate memory. And this is something we need” .

The work accomplished at Piton Rouge was never “the object of an exhibition”, in the aesthetic sense of the term, nor was it reproduced in a published work. It bore no signature, but remained an “open work”. People hiking here often added a stone or two, their signature. Were they aware of contributing to a work of art? Was their intention imbued with the sacred? Were they giving homage or making a gesture that was like an obscure ritual linked to the place and its aura? Wilhiam Zitte leads us to question the limits of the sacred and the profane. It was like the ‘Ti bon dié’ (little altar) the artist created by a roadside and that the population appropriated for themselves by laying down gifts of flowers, candles, incense and so on, not realising that it was actually the work of an artist.

Wilhiam Zitte’s art is a funerary art. His ‘Têt Kaf’ are fighting to stay alive, fighting death “that land where you go to lose your memory,” in the words of Chris Marker . His main challenge, even when exhibited in sites of contemporary art works (galleries, institutions and other temples of art), was above all an aesthetic one. His is a cultural art-form, like African statues and masks or Coptic effigies: they are vehicles of vital forces, sacred representations, “victorious faces repairing the fabric of the world” . Their main objective is not to be sold and hang on the wall of an art-gallery or someone’s living room, but to give voice to the thousands of men lost to oblivion, to rebuild the link between the living and the dead. “What documents do we have,” asks the artist, “to tell us that slavery existed? With the exception of a few notarial deeds, what traces are left ? I recreate the archives. We need such lies. By painting the portrait of a mythical ancestor, Zitte’s project thus fills a void, responding to the imperative necessity to recount, show and give a face to those Carpanin Marimoutou refers to as

“ghosts” . Transforming the ‘Kaf’ (black person) into a person watching, bringing him out of oblivion, giving him a presence, an existence, ‘re-presenting’ him, amounts to changing his status. He is no longer a ghost, but has become an ancestor.

Wilhiam Zitte’s art is political art, in its desire to construct a different image of the black person in the Reunion of yesterday and that of today. Representing the rebellious black man, the black man standing upright, the mystical black man means first of all making a break with appeasing representations and with the image of submissiveness transmitted history. He also refuses to take a fictional stance, which could people his universe with invented figures, and chooses rather to base his work on documents and traces having archaeological connotations. This allows him to be part of reality, anchoring flesh and blood beings in the truths of history. “Our identity contains in its foundations an element, a component that has not been taken into consideration. Our action is aimed at making sure it is. If we always talk using ‘joking’ terms, in terms of humanistic criticism, if the image of the black man always refers to caricatures, like the ‘golliwog’ in Noddy… Still today, the black man is presented from the outside, we have the image of the American black man, which is quite surprising. But where is the image of the black man in Reunion? Who defines him?” . His work on the image of the black man was part of a more general analysis of the history of art and the issue of aesthetic criteria . He constantly invited artists to work on the question of memory, notably through the collective exhibitions he curated: ‘Bwadébène’ (Ebony wood) in 1997, ‘Aboli pas aboli l’esclavage’ (Slavery: abolished, not abolished), in collaboration with Julien Blaine and André Robert in 1998. Consideration of the history of Reunionese art, Creole art, being one of his major preoccupations, he considered it absolutely essential that it should avoid being locked inside a uniquely Euro-centred vision. His stance thus espoused the global cultural and political notion of ‘Black is beautiful’ (which he translated into Reunionese Creole as: ‘Kaf lé joli’), or that of ‘Négritude’. He prolonged it with a questioning of artistic and ethical criteria, including those that determined popular representations linked to phenotypes: “Because the Indian has a fine nose and straight hair he is more handsome than the African with his thick lips. I refute these aesthetic generalisations” .

Ultimately, rather than a homage or a memorial to a world inhabited by ancestors roaming tombless, Wilhiam Zitte’s ‘arcreology’ creates “figures who at last permit the process of mourning” and thus lays down the foundations of a “civilisation claimed to be infused with meaning and myth, at one and the same time based on premises and fantasy, dream and reality, also a Creole civilisation” .

Following a ten-year absence, Jack Beng-Thi came back to Reunion at the age of 28. After studying at the School of Art of Toulouse and the University of Paris VIII, he travelled widely in Europe and Latin America. The break with his island, as well as his encounters with other civilisations, gave birth in him to a feeling emptiness, confronting him with issues of emptiness, of void and absence of memory in the society. 400 years of history is very short, but when this history has been whittled away through collective oblivion in the society, on what bedrock are we to construct representations of the self and of our people? No traces, no images remain of the slave trade, so few written documents on slavery and so much silence! While, in the words of Chamoiseau, the “truth” of slavery has been lost forever through lack of personal testimonies and while no one is able to given an account of the horrors of the slave trade, it seems, nevertheless, that plunging into the hellish reality of the holds of the ships is a necessary condition for emerging out of the dark night of the colonialism. Like a beacon for the spoken word, the artist becomes the litmus paper, creator and direct witness of a memory he incarnates.

In 1977, representing the School of Art of Toulouse at a residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, the artist was able to search through the archives of the hôtel Soubise, whilst studying for a Bachelors and then Masters degree at the University of Paris VIII. He read the Black Code (Code Noir) from cover to cover. “That was when I became aware of the issue of the body,” he declares. “what the body had to undergo. The physical issue connected to the denial of the person. I consider this to be the fundamental issue” . Like Orpheus in the underworld, Beng-Thi set out on a quest: going in search of those drowned by history, exploring the hell of the ship’s hold, to retrieve and reincarnate its ghosts, taking the risk of being turned into a pillar of salt. “When carrying out my research, I experienced the body lying down, experiencing suffering and anguish … I place myself inside this history,” he says .

Following on from this journey through the archives, there was his encounter with matter. “I started to work on the body and to position it (…). There being no written documents, no books recording this chapter of our history, (…) I consider my creative work to be an important medium that will give an account.” The artist elevates his direct experience, his presence, to the level of witness, infusing the imagination with its primary function of constructing in the present on the bedrock erased by history but out of which man can once more rise up.

It was in his workshop Beng-Thi re-enacts and transcends the drama. A large tub contains clay magma that the artist waters, with movements recalling rainfall. Plunging his hands into the earth, he uproots strips of naked flesh. The earth, as primeval matter, becomes the fundamental choice of material made by the artist, giving him physical contact with the body: “By touching this earth,” he declares, “in a totally metaphoric manner, I touch the skin and the body, physically. A tactile experience” . Before our very eyes, a body is created, still lying down, still sleeping. After an initial drying stage, the sculptor takes the body out of its plaster sarcophagus and immediately places it upright, vertically: a figure now standing up straight. Another comes to join it soon, then a third … the artist then takes them one by one, giving an individual identity to each of these identical forms. His hands mark the matter, still damp, closing up accidental gaps, healing wounds, repairing flesh, grafting skin, tending broken bones. Workshop accidents, accidents of history, the artist erases time, using his fingers to reunite “the splinters of the skin scattered by the wind” .

This period in the confinement and secrecy of his workshop is an essential step to the understanding of Jack Beng-Thi’s creative process. It is at this precise instant that the artist repairs history and incarnates through matter the ghosts of the maritime tragedy, permitting mourning to occur at last. He deliberately makes use of medical vocabulary when describing his process and explains that using plaster and metal prosthetics to enable the bodies to remain upright is far from innocuous. However, he is not simply a doctor, but also takes on the role of magician when, with a gesture similar to that of certain exorcism rituals, he scatters a mixture of coloured earth over the bodies . Incantations follow on closely, seemingly uttered by the very mouths of the figures, awakening after a long sleep. The artist talks of a foundational, manifest and transcendent act, announcing a mental renaissance, overturning images to achieve the new reconstruction, enabling the emergence of the long-awaited metamorphosise .

In the hands of the artist, a transmutation takes place, the workshop becoming the antithesis of the hull of the slave ship: inside this alchemist’s athanor a new race of man is born, standing upright, marching forward.

Au fil de la mémoire, Les Bouts de bois hurlants, Nostalgique sweet vacoa, Arrachement Carg. C12, Territoire Maïdo/Incision/arrachement, Ligne Bleue-Héritage, La constellation des manquants... (The thread of time, Screaming splinters of wood, Nostalgia of sweet screwpine, Wrench Cargo C12, Territory Maïdo/Incision/Wrenching, Blue line-Heritage, Constellation of those missing). The works of Beng-Thi, with their evocative titles, raise the question of the body and its territory or territories and it is through the memory (a memory to be explored, enlightened and reconstructed) that he will create the primary and generic link that turns a group of bodies into a people standing upright.

The issue of the body and that of its representation are fundamental. After having “extracted them from the archives”, as he says, the artist is confronted with the question of how to represent them. In the majority of the works he created in the early 1990s, the body is physically present through semi-realistic representations in terra cotta. For each series, they all come out of the same mould and are of the same size, which varies from installation to installation and can reach a height of 1.6 metres. They are like antique busts disproportionately elongated by the artist, who adds on a monolithic torso with no legs or arms, akin to mummies or chrysalides to which a head has been added. The bodies are simplified, minimalist. The absence of anatomy and any notion of proportion in the western sense of the term brings Beng-Thi’s work close to the traditional sculptures of sub-Saharan Africa or Egypt, the purpose of which was to provide a support for the immortal ‘double’ of the ancestor after the physical departure of the person deceased. According to Cheikh Anta Diop who refers to ‘the African cannon’, the realistic character of the representation, whether the arms or torso are too long or too short, is of little importance, since they are merely the symbol of the ancestor, now returned and present in the midst of the living.

The upper part of the body (shoulders, neck and head) are generally modelled realistically. The remaining sections of the body disappear into the torso, the shape of which varies from installation to installation.

Hold your head up, stand up straight … While the body is at times reclining (as in Mira Slum, Arrachement Carg. C12), more often than not it is vertically upright, its posture dynamic. The bodies are attached, anchored, bundled up, but they manage to stand upright and exude a high amount of synergy. From these conflicting impressions of paralysis and movement is born the idea of combat, of struggle. It is as though these heads, seemingly gifted with language, have emerged out of their matrix and shaken off their iron shackles. String, rope and thread, very much present in Beng-Thi’s works, contribute to creating this ambivalence: rope, natural and coloured raffia, wire, nylon fishing lines, optic fibre: all of these attach or liberate, link together or suspend, decorate and create repetitive patterns on the surfaces.

Also, the body is rarely represented alone, but as part of installations that can number between 2 and 30 figures. The artist moves from creating statues to setting up installations and the group of bodies set up in the space creates the impression of movement. The collective dimension is very much present in the artist’s technique. Having started off searching for his own origins and that of his family, Ben-Thi ended up giving voice to and constructing his people. He declares: “I represent my body. The body of others too. It is us. It is our history. I place myself inside this history.” What he is interested in, beyond the Vietnamese and Bengali origins of his family, is the way “the bodies were wrenched from the continent to be shipped to the island.” This projection in space, in that very specific historical and political context, gave rise to the birth of a people. The idea of the genesis of a new people is what enables him to transcend the body, “the body fragmented in its finiteness, its disaster and its vulnerability” .

From the start, the question of territory became essential, leading him to explore spaces buried deep down in the memory: plunging deep into the hell of the ship’s hold, sailing the seas where, to the visionary eye, there still lingers “the smoke of the higher events, where history still burns,” diving to the depths of the ocean in search of the bones stripped naked by the salt, gazing “behind the landscape” of the island, where the shadows of peoples toiling under the yoke of the master are still hidden and giving expression to the melancholy linked to the impossible return to the fantasised ‘elsewhere’ that is the motherland … Explicitly, many of his works contain references to this issue of place, even in their titles. Both in his in situ works such as ‘Territoire Maïdo/Incision/Arrachement’ , or his installations, such as ‘Ligne bleue-héritage’, exhibited at the Biennale of Cuba in 1997, or ‘Au fil de la mémoire’, the works of Beng-Thi record the ambivalent link tying us to territories, whether these are our motherland, our territory of choice or the ocean, at the same time shroud, insurmountable liquid barrier and sacred element with purifying properties. Jack Beng-Thi’s technique is part of the process of “reconquering” territories pillaged by history. He declares: “For too long we were confined to spaces that were too small, the hold of the boat, the sugar-estate and prohibitions of all kinds.” While all the early works he exhibited were small-format friezes, in the years to follow, very quickly his bodies stood upright and were placed in a space, initially through his use of rounded sculptures and their positioning in his installations. The artist also creates an opening onto a transcendent space, materialised through certain works that recall the infinity of the heavens, a metaphor of the spiritual dimension, also very much present in his work: ‘Territoire stellaire’, ‘150 gardiens au pays des étoiles’, ‘La constellation des manquants’, ‘La pyramide aux esprits’ (Stellar territory, 150 guardians in the land of the stars, The constellation of those absent, The pyramid of the spirits) The symbolic space of freedom and that of conscience are also the foundations of a new relationship with the island, opening out the space of ‘ourselves’, enabling the reconstruction the generic link and building a foundation for the society.

The work of Beng-Thi can be seen as a funerary homage, a funeral rite for “the countless frizzy heads buried nameless in the abyss” . Achieving the status of ancestor enables them to feed and support present and future generations. The body has been repaired, stands vertical: the upright man who will found the society. And when he refers to the victims of the slave trade, Beng-Thi declares: “they are the ones who keep us alive”. He belongs to the current of the anthropological substrata, from the east coast of Africa to New Caledonia, passing through the large island of Madagascar, the earth where the mortal remains of the ancestors have been laid to rest and which is the privileged site of anchoring of the group. This territory is Reunion and the Indian Ocean.

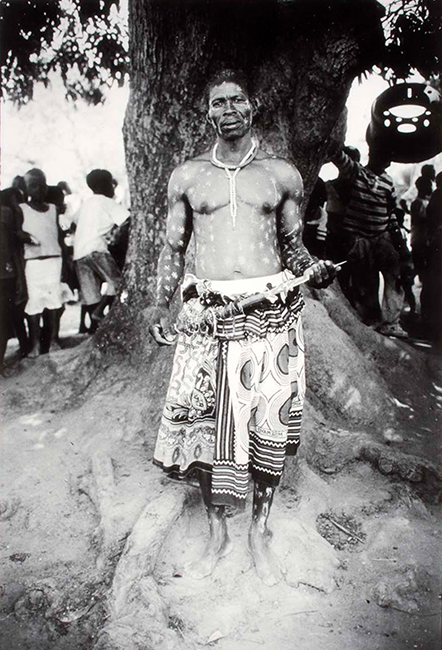

Karl Kugel is a photographer and visual creator. Notably awarded the ‘Hors les Murs’ grant by the Villa Médicis for a project in China, he was one of the co-founders of the group of photographers BKL, which, from 1990 to 1994, recorded the evolution of three neighbourhoods in Reunion, through a creative publishing project entitled ‘Entre Mythologies et Pratiques’ (Between mythologies and practices) bringing together photographers, sociologists, artists and philosophers. He has settled on the island and has deployed work deeply anchored in the territories of the Indian Ocean (notably Mozambique and South Africa). As the epicentre of his artistic creation, he explores the relationship to the body, to the sacred and to territories, applying a poetic and artistic approach of ethnographic dimensions with deeply political and symbolic messages: ‘Récits des corps’ (Narration of bodies) (1997-2002), ‘Camp Calixte’ (2003), ‘Et les engins vont Retourner la terre’ (And the machines will turn over the earth) (2004), ‘Makwalé’ and finally ‘Le Jardin de la mémoire’ (The Garden of Memory), which he created at Ilhà in Mozambique, as part of the UNESCO ‘Slave Routes’ program.

Renewing dialogue, linking up practices and territories, creating a link: the work of Karl Kugel draws its essence very exactly from the place where human and artistic adventure are born and develop. At the centre of his work there is the link, woven like a victorious response to the violence of history, to the exile of human groups wrenched away from their land and deported. The link with the body, link with the sacred, with the earth and with the motherland: the link which is the foundation of the place and which places Reunion inside a space shared with the Makwa region, but also with Madagascar, Mayotte and South Africa. The Indian Ocean is a vast country and through memory, dialogue between cultures and fertile encounters, Karl Kugel explores this space.

His work on the tradition of martial arts, common to the descendants of slaves, led him to work with photographers from Mozambique (Ricardo Rangel, Kok Nam etc.). He set up regular exchanges between the two countries, producing a series of images later gather together for an installation, then published in a book entitled ‘Saudade de l’espoir’ (Saudade of hope), a work which, in the words of the artist “oscillates between bearing witness to a period of silence in the history of Mozambique – the the period of colonisation and its social system of apartheid, followed by almost 15 years of Civil War – and the emotion felt in the face of the profound beauty of life” .

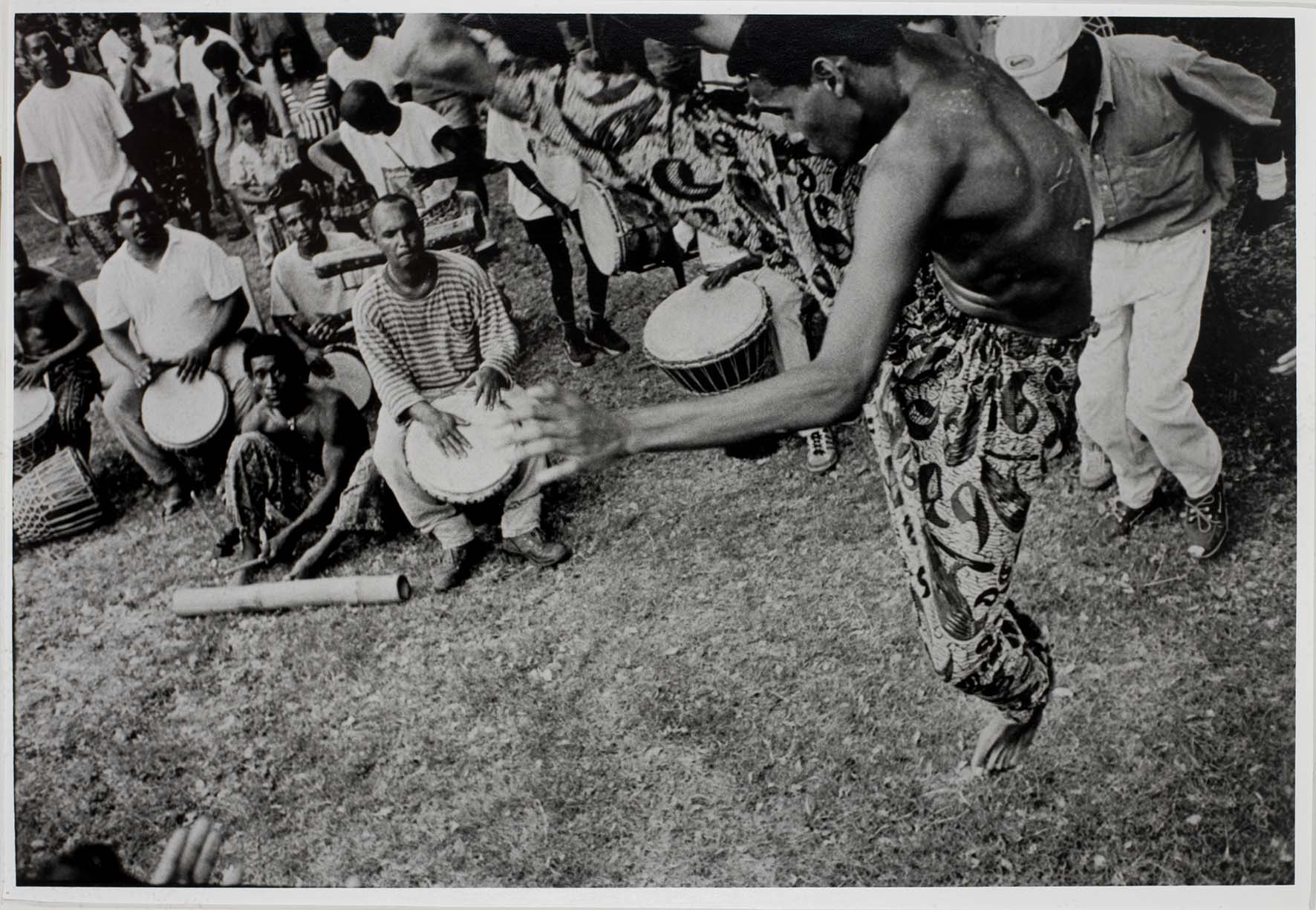

Created during his regular comings and goings between Mozambique and Reunion, ‘Makwalé’ is a “lay ceremony”, which Karl Kugel refuses to refer to as a ‘performance’. A multifaceted and recurring work combining images, singing, poetry, music and martial arts. It calls up the cultural markers common to the two cultures: from the ‘Jako’ in Reunion, a mysterious character from Indian belief, to the ‘Wanalombo’ of Mozambique, a ‘divine’ mediator and key to the initiation rites of the Makondé people” . With over 400 photographs, a film showing Promès, the last Jako and a circle of participants which grows with each new public experience, Makwalé is a visual and living creation which, according to Karl Kugel, “explores the paths of history, of the mystical and imaginary universe that surrounds the martial arts. Around the circle, at the heart of the human village, Makwalé evokes exile and its violence, amnesia, but also hope, dreams and belief in beauty.”

As a continuation all his work on creating links, in 2003 Karl Kugel embarked on the construction of the Garden of Memory in Mozambique, under the impulse of the historian Sudel Fuma . The project was given form on the island of Mozambique, in the region of Nampula, on a plot donated by Ministry of Culture of Mozambique. True hub of the slave trade, the island of Mozambique was the site of the forced departure of hundreds of thousands of women and men shipped to different destinations around the world (Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, South America, the Caribbean and North America). Located at the crossroads between different civilisations, it was the capital of the country until the end of the 19th century and played an important role for trade in East Africa. From this period, it has retained a magnificent architectural heritage and in 1992 was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Karl Kugel structured the Garden of Memory on the basis of a pattern linked to martial arts, creating a series of “ron”: circles traditionally traced by the dancers of Moraingy (martial art of Reunion) before the combat and given various functions. A first ‘ron’ is devoted to walking, a second is seen as a space of initiation, surrounded by busts sculptured by Mozambican (Elias Joao Mungus and Manuel José Rita) and Reunionese (Sophie Bazin et Johary Ravaloson) artists. The third circle opens out onto the sea, overlooking the empty space, to which each person can give the meaning he or she thinks fit. The garden expresses the desire to reveal and consolidate a memory common to the people of the Indian Ocean “reminding the populations of the countries of the Indian Ocean of the links that have united them throughout history and, through what they have created in our respective cultures, that today can contribute to the construction of a common destiny” .

Wilhiam Zitte, Jack Beng-Thi and Karl Kugel each in their own way have produced committed works of art, proposing ways to read the present where a reconstructed and fertile memory plays an important role.

When Reunionese artists treat the issue of slavery and the slave trade, they are building on a substratum of silence and emptiness in respect of memory, nourishing creation in general, producing the need to speak, reveal and denounce but also to repair the body and restore the image, with the aim of re-appropriating history and constructing a common foundation. Patrick Camoiseau spoke of “naming and constructing in the respect of the memory that is absent” .

Broadly speaking, artistic creation is seen as the political act of a symbolic reconquering of territories looted by the slave trade. It begins with the body, in its demise and its transcendence, representation, movement, language, words, but also the relationship with the self, with others, the link with the motherland and with the island. It can also be seen as a sacred, funerary, ritualistic act, linking the deceased with the present and raising those who have disappeared to the level of ancestors, permitting the construction of a collective resilience.

Questions of escaping and insubordination also constantly recur, both in the topics treated and in the attitudes of the artists. This is the case of the works by Christian Jalma, or Pink-Floyd, then Floy Dog, who actually exhibited with W. Zitte, J. Beng-Thi and K. Kugel. According to Aude-Emmanuelle Hoareau, his creations “reactivate hope and fear, going beyond the historical framework of slavery, of a non-domesticated body which, through its capacity for rebellion, becomes liberated” . Through his multifaceted and tentacular works (videos, performances, novels, poetry, musical compositions including an opera), the poet-artist offers a fascinating theory on the integration of the black person in the Reunionese society and his wanderings towards his hypothetical origins in search of an identity . He also treats questions of amnesia and memory, Creole expression and the construction of ‘Creolisation’, which he sees as a trap, going so far as to invent a language known to him alone and demanding the right to write in a version of French riddled with errors . He also embarked a lecture of history going against current trends, setting up the ‘Nenène’ (nanny) as a central pillar in the construction of Reunionese culture and society . Stronger then amnesia, the figure of the ancestor is omnipresent in the work of Floy Dog, “that ancestor whose traces have been lost, the slave forgotten by history but still alive in our chromosomes-memories .

To quote Marie-Josée Matiti-Picard, when poets, writers and, in this particular case, visual artists revive the memory of the tragic history of the island through the topics of slavery and the slave trade “it is actually a representation of our origins they are offering us” . The emergence of a Reunionese memory thus rests on the anchoring, the engraving of the discourse in history and within the space of the island. Reunion does not have a founding myth, but a founding people.