Bourbon island became a French colony in 1640, but was only truly colonised under Colbert as from 1664, with settlement by Europeans, Madagascans and Indians. The ordinance of The Hague issued in 1674, forbidding mixed marriages, established a form of discrimination necessary to the construction of a society of slavery. Initially forbidden in the statutes of the French East India Company , slavery was first of all practised, then progressively legalised on the island. With the development of the plantation economy, the number of slaves progressively increased and around 1715, the servile population was in the majority. It became necessary to draw up a local Black Code, in the form of the Letters Patent of 1723. The servile population of Bourbon island essentially originated from Madagascar, East Africa and, to a far lesser extent, West Africa and India. The system continued until Abolition in 1848.

How to ‘resist’ when you were a slave in a plantation society?

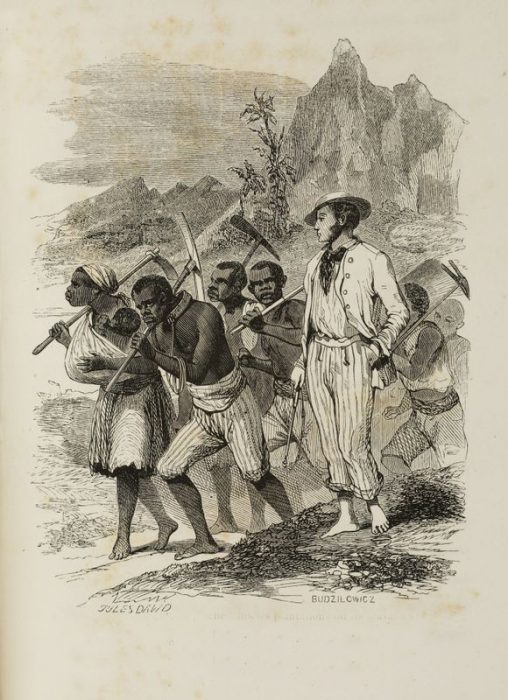

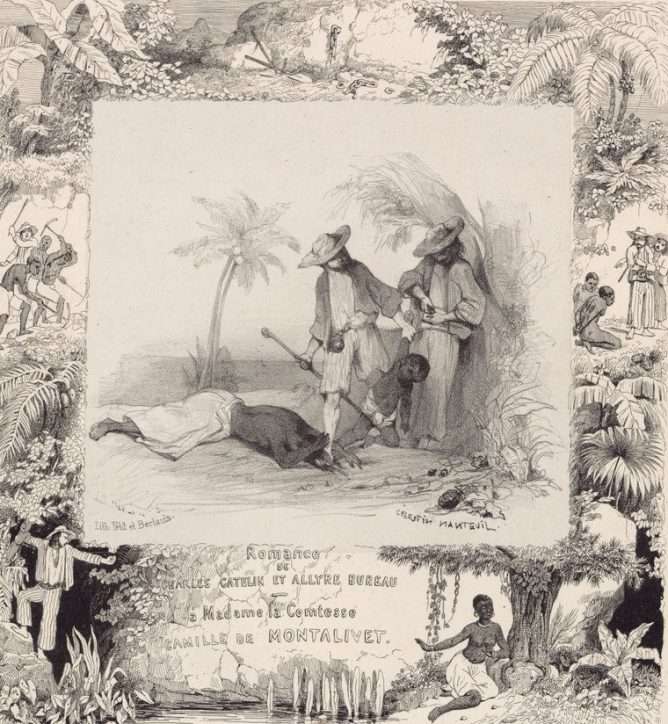

Constraint, exclusion and violence were the pillars of the system of slavery. Various methods of coercion were applied to obtain high performance at work, both in master-slave relations and through day-to-day social segregation.

Fundamentally, the slave had no other option than to try to counter the economic, social and physical violence through a number of actions of opposition we can refer to as resistance.

These mainly took on two forms: ostensible and illegal forms of opposition and forms of resistance that prevented the smooth workings of the society through unexpected collateral effects, but were not necessarily illegal.

Alongside identity restructuring, difficult to quantify by historians, there existed the preservation of rites, language, know-how, alongside means of defence ranging from laughter to suicide, material adjustments, of which we have records in the legal archives.

When the slave Pierre-Paul, a Creole aged 60, appeared in court on 14th July 1840, accused of theft committed during the night, with housebreaking and serious violence committed against Mr Joseph Ricquebourg in the district of Ste-Suzanne, he was caught in the act by the guardian of the chicken-coop, whom he attacked using an axe. The magistrate retained attenuating circumstances and Pierre-Paul was sentences to 5 years in chains and 30 lashes of the whip.

This was a common case of theft, since it involved a man (94 % of cases), a Creole (48 % of cases) attacking the property of a free person (63 % of cases) but causing, as was often the case, collateral damage to a third person, a slave, exercising a risky profession (the guardian). The object of the theft was also common, the slave attempting to steal food or cattle to feed himself: the state of malnutrition, at times chronic, was often the cause of petty thefts. What was also common was the use of violence after being caught red-handed, theft being an obvious cause of violence. What is less common in this particular example was the age of the slave (60), the average being around 30, which leads us to conclude that Pierre Paul was in an extremely precarious situation. Finally, Pierre-Paul came out of the shadows and, through his attempted theft, demonstrated his refusal to accept the conditions of his existence.

Les archives are full of similar examples; theft, in its various forms, was the most common expression of resistance to slavery. The authorities would regularly express their concern regarding this scourge. In a letter addressed to the king’s General Commander in 1817, the public prosecutor mentioned the “impunity, particularly just before the rainy season, the rains being the worst of the year, which leaves a large number of labourers with no work and no means of earning their living.”

Day-to-day theft and concealment of the stolen goods led to a high level of trafficking involving a large section of the island’s poor whites or free coloureds living on the island. To a certain extent, the authorities tolerated this parallel

economy , while at the same time fearing alliances within the poor population and constantly attempted to maintain public order. The judicial system was particularly attentive to forged documents, meting out severe sentences on any poor whites involved in such activity:

Abusive actions carried out by certain persons issuing written authorisations to slaves enabling them to sell goods that do not belong to them by forging the signature of their master encourages Blacks to steal (…) it was absolutely essential to set an example to intimidate those who might issue forged documents, also going against public order.

Thus physical preservation, very often not seriously taken into consideration in studies on resistance, was, however an essential element of actions of rebellion by slaves: a means of adjustment aimed at surviving the conditions of day-to-day life.

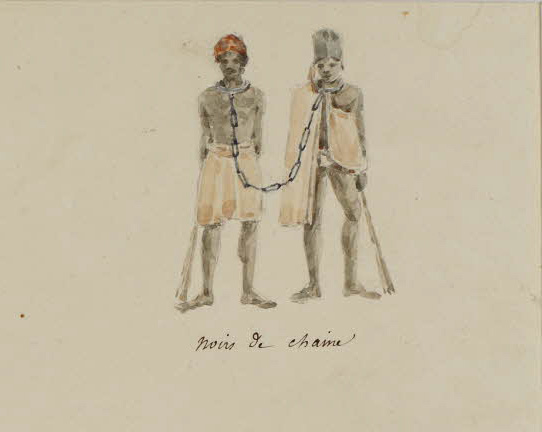

‘Resistance through escape’ consisted in the slave “breaking his chains” and experiencing freedom. Such escape, referred to as ‘maroonage’, involved breaking away from the slave’s living space, thus suspending the alienation of his existence. Intermittent or permanent, such escape existed from the very beginnings of slavery and continued to do so, remaining an important means of rebellion right up to Abolition.

For example, in a report issued in 1839, we have an example of a form of solidarity between slaves regarding the arrest of Jupiter and Pierre-Louis on the outskirts of St-Pierre. On their way to their station, the militia patrol walked past their house and was surprised to see slaves, including the foreman, responding to calls for help by maroons.

Léonard, first foreman, addressing the militia in an authoritative tone, ordered them to release the prisoners and coming up against their refusal to obey such orders, immediately attempted, with the support of other Blacks, to deliver Jupiter et Pierre Louis using violence, at the same time each struggling to escape.

There followed a fight notably opposing “corporal Berdinin and the different slaves, who were at an advantage until the neighbour Dame Payen intervened and called for reinforcements.”

Death sentences for long-term fugitives appear fairly late on in the archives. In January 1842, when Fantaisie, “a bad element” belonging to Mr Deguigué and sentenced to life in chains in the jails of Saint-Denis, succeeded in escaping to the mountains on the island, he was actively pursued by a detachment. Bravely defending himself, he attempted to assassinate several of his hunters, including the chief hunter Louis Marcelin. During his trial, accused of “attempted murder with premeditation, assault and rebellion against members of the detachment with no attenuating circumstances and a repeat offender”, he was, unsurprisingly, sentenced to death.

The reasons for escaping, noted in the archives, were very often extremely circumstantial. Slaves would escape out of nostalgia for their native country, because they had been shamed on the plantation, out of fear of punishment for a fault committed or as a reaction to violence too frequently inflicted …

During the long period of slavery on the island, maroonage was more or less an important phenomenon, but without ever concerning more than 10% of the population. While the fairly small numbers and the intensity of this opposition never led to the emergence of any ‘Spartacus’ taking the lead in a generalised rebellion, , maroonage enabled slaves to escape from an alienating situation, while to a certain extent for the whites it was a safety valve, avoiding risk of civil war. The police, legislative authorities and the judiciary thus kept a close watch on such movements, while adapting repressive measures to channel them.

The concern of the authorities and the continuous renewal of repressive measures are enough to make us understand the extent to which the Colony feared any emancipation movements. No need for heroes, the fear in itself was an indication of deep resistance to the established order.

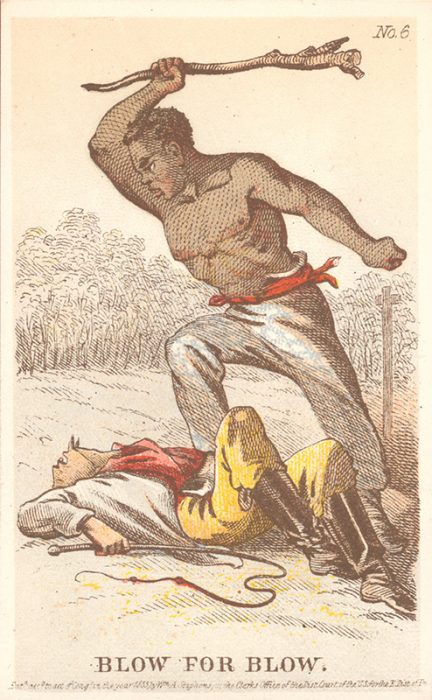

‘Resistance through violence’ was the most radical, visible and the most feared form of opposition, underlying different forms of resistance and varying in intensity: minor violence liked to theft, insolence during work going as far as physical aggression; the slave might attack his family or himself in an attempt at self-destruction. Finally, his action could represent an attempt to deteriorate or destroy the tools necessary for production and at times execution of representatives of slavery or any persons, including other slaves, standing in his way. The common denominator of all these forms of opposition was the aggressive act, violence, if we retain that each could be passive or active, premeditated or impulsive, conscious or not. It is easy to understand why this from of resistance has left us with a large number of examples in the archives, right up to the end of the period of slavery.

In a case involving arson and murder, tried before the criminal court in June 1840, the discussion concerning mitigation of the sentence gives an interesting insight into the protagonists and the workings of the judicial machinery.

(…) The named Thomas et Avril have been accused of setting fire to the hut of the one named Quentin, their foreman, and making an attempt on his life. Thomas claimed he had reasons to complain of the foreman; he told Avril and informed him of his intention to set fire to Quentin’s hut. Far from discouraging him, Avril spurred him on to take avenge, even though the reasons were of little foundation, but set the condition for participating in the proposed crime that before setting fire to Quentin’s hut, they would barricade the door, so that he would have no way of escaping death.

Both sentenced to death by the Criminal Court of St-Paul on 22nd June, a debate followed concerning a more lenient sentence for Thomas between a master opposed to this, declaring it to be “a false philanthropy that pushes today’s generation towards the destruction of the all the society’s safeguards” and a magistrate who declared that “It would be an example of strictness to punish with a more severe sentence the one who, moved by revenge, conceived the idea of setting fire to a hut, than the one who cold-bloodedly proposed the means to stifle a human victim in the fire.” His sentence was finally reduced to penal servitude for life.

While homicides were regularly judged and led to sentencing , arson was rarely recorded. Here the foreman, a commanding slave, was the object of the violence. Representatives of the slavery society inside the group of slaves, they were often victims of resistance by the slaves.

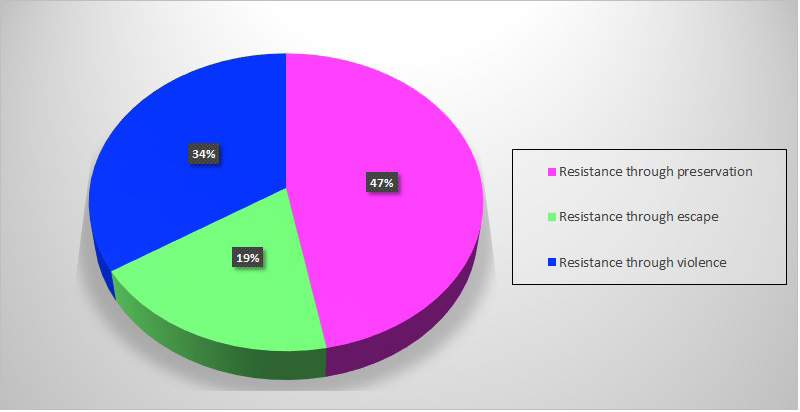

These three examples of rebellion by slaves seen in the perspective of a wider quantitative approach give us a more accurate vision of the reality of resistance to slavery. The colonial regime attempted to set up an ideal hierarchy based on constraint and domination. Any action, legal or illegal, aimed at disturbing this ideal was a form of resistance. Very often far from spectacular, it was organised on a day-to-day basis, adapted to the context, becoming a long process of undermining the system.

For a slave, breaking the law was not equivalent to a criminal act committed by a free man. An illegal act by a slave obliged the colony to integrate him into the society of men: his responsibility was finally recognised and destroyed his status as “mobile goods”. To this we can add all the unquantifiable forms of opposition applied by slaves in their struggle against the disintegration of their identity.