There exists no opposition or antagonism between these two, which both resulted from specific and complex situations within each estate, as well as from the historical context.

Escape, short or long-term, was more often than not an individual act, carried out in silence, consisting in the slave fleeing towards the interior of the island and taking shelter in the mountains and cirques.

This sometimes led to several individuals together setting up camps of fugitives. The archives also indicate that fugitives would organise forays into the habitations in search of food, tools and sometimes women companions. Existing as from the very start of settlement, the phenomenon of escaped slaves became a constant reality in the history of Bourbon island.

In the years preceding the abolition of slavery in 1848, there existed several hundred fugitives, some having gained their freedom for over 20 years.

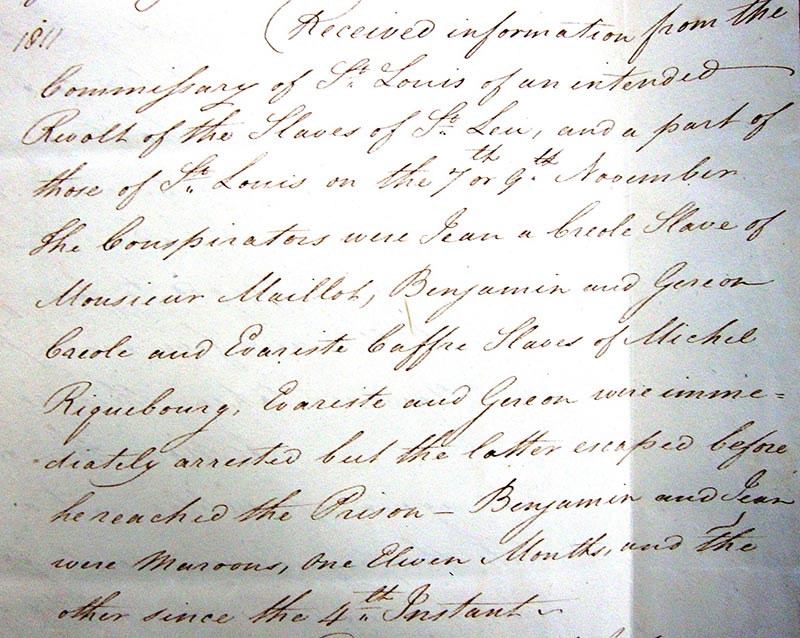

During almost two centuries of slavery on Bourbon island, with the exception of a small handful of plots to organise revolt, soon extinguished, the 1811 revolt in Saint-Leu was the only one to have been implemented in its entirety.

A study of the insurrection indicates a strategy characterised both by its collective character and by a desire to eradicate the system of slavery.

It was characterised by slaves working in the island’s higher areas coming down to the coast, where part of the free population resided. The movement took place in an atmosphere of noise and fury and resulted in a reversal, even a revolution, in people’s behaviour: the whites became openly afraid, fleeing before the fury of the slaves.

Despite the apparent opposition between slaves revolting and those fleeing, the Saint-Leu insurrection indicates close links existing between the two types of behaviour. Whether before the insurrection, during its occurrence or in the months that followed, the phenomenon of fugitive slaves was constantly present.

While the notion of individual revolt by slaves contributed to the masters’ fearing acts of violence, pillage or crimes, it was, however, the collective character of the revolt that stoked the fears experienced by the plantation owners, leading them to set up protective strategies. Consequently, permanent whippings, ethnic diversification on plantations, as well as dietary and health conditions aimed at maintaining individual slaves in a state of controlled weakness in relation to the needs of a workforce for agriculture, became tools used to dominate the slave population. The idea, organisation and implementation of a collective revolt thus became very difficult to carry out and dependent on a number of factors.

The insurrection in Saint-Leu directly concerned over 200 slaves of various origins (Africans, Madagascans and Creoles) and having various functions (agricultural workers, house servants, smithies, overseers etc.).

The revolt was prepared day after day over several years: the final decision to act was almost certainly determined by the island being taken over by the British at the end of 1810 and by the masters being partially disarmed as a result. The ‘war’ concerned was extremely violent in character, on the side of the insurgents, as well as that of the whites, with two or three killed directly or indirectly, and also the ensuing ferocious repression. Dozens of insurgents were either killed during the conflict or died in prison. Of the twenty-five condemned to death, seven were pardoned, three died in prison before being executed and fifteen decapitated with an axe in five different towns, to serve as examples.

If the idea of revolt was constantly present in the minds of many slaves , it became a reality in Saint-Leu as a result of a natural cause: due to a permanent lack of water in the region, the slaves in the south of the district necessarily gathered together each day to carry water from a pool permanently filled from a spring situated above the estates, in the gully called ravine du Trou.

This was where slaves belonging to different masters would meet and where the project of the revolt was initially organised. This was the first objective element enabling the dissemination of the idea of a revolt.

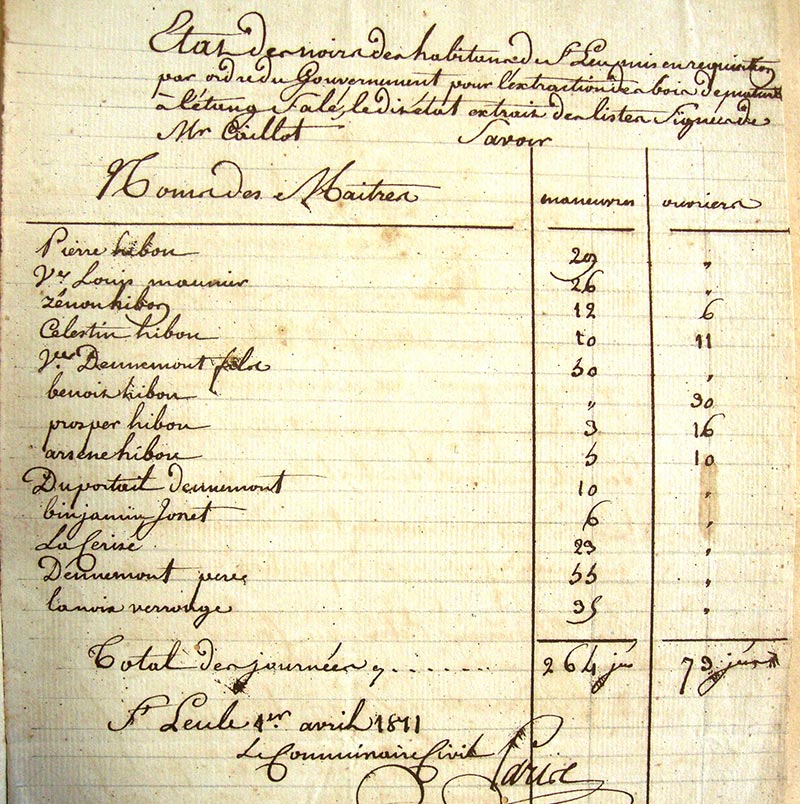

The political will of the insurgents to escape from servitude, but also to destroy the system as a whole, was reinforced by the contacts made with slaves from the district of Saint-Louis. The second determining element occurred during the work of handling tree trunks to be loaded onto a British vessel – the Windham – in the bay of Etang Salé in December 1810.

For close to two months, slaves requisitioned from each of the two districts developed and matured the idea of a common revolt.

A reading of the interrogations of the slaves accused brings out the fact that it was during these exchanges that the slave named Figaro declared he was able to lead several slaves from Saint Louis to revolt, which turned out to be false and set off repressive measures and the premature start of the revolt.

A third element that facilitated the preparation of the revolt was that several slaves from Saint-Leu, including Elie and Gilles, who were later shown to be the leaders of the movement, decided to escape following the work on the Windham.

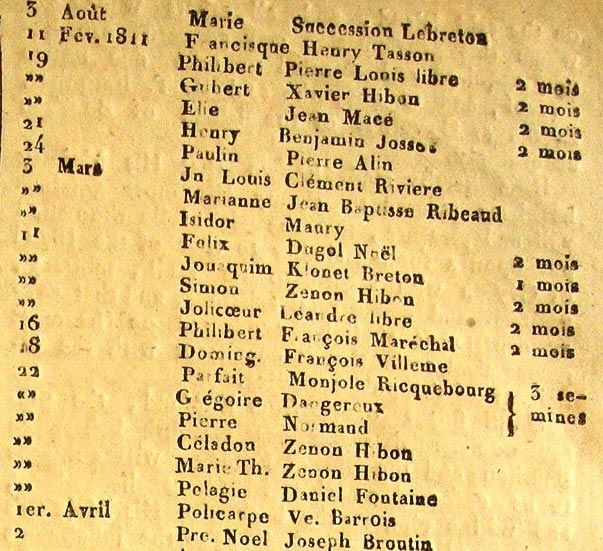

As from 19th February 1811, they are recorded as fugitives imprisoned in the jail of Saint-Paul, where they remained for two months. Here, they encountered other slaves who had been imprisoned, coming from estates in Saint-Paul, including some belonging to Mme Desbassayns, in general imprisoned for attempting to escape . This explains the presence of slaves from Saint-Paul and Saint-Louis in the list of those arrested following the revolt in November 1811. Above all, it demonstrates the fact that the revolt represented an attempt to confront the system of slavery well beyond the geographical limits of Saint Leu.

Among the salves imprisoned in Saint Paul, for example, there was Philibert, a slave belonging to a freed coloured master ‘detained in jail for attempting to escape’ and who died on 9th November 1811, certainly as a result of wounds sustained during the ‘war’ against the whites.

Other slaves who had worked on the Windham also appear to have taken refuge on the ship, for a time benefitting from the protection of the British sailors. On the vessel, they also obtained the flag they were later to brandish during the revolt.

While in 1810 only a small number of slaves from Saint-Leu were jailed in Saint-Paul, from February 1811, many more were incarcerated here and retained for several weeks, including a few women. Here also, contacts between slaves from different estates not necessarily close to the water basin contributed to the dissemination of the idea of a revolt.

The revolt broke out on 5th November following the arrest on the previous day of slaves from Saint-Louis denounced by Figaro. Certain of those imprisoned had already been qualified as fugitives: Jean for a few days and Benjamin for 11 months.

On 7th November, when the insurgents came down to the estates from the pool, accounts, particularly those given by the slaves themselves, tell of confusion between ‘insurgents’ and ‘a band of fugitives’, coming to pillage the mansions:

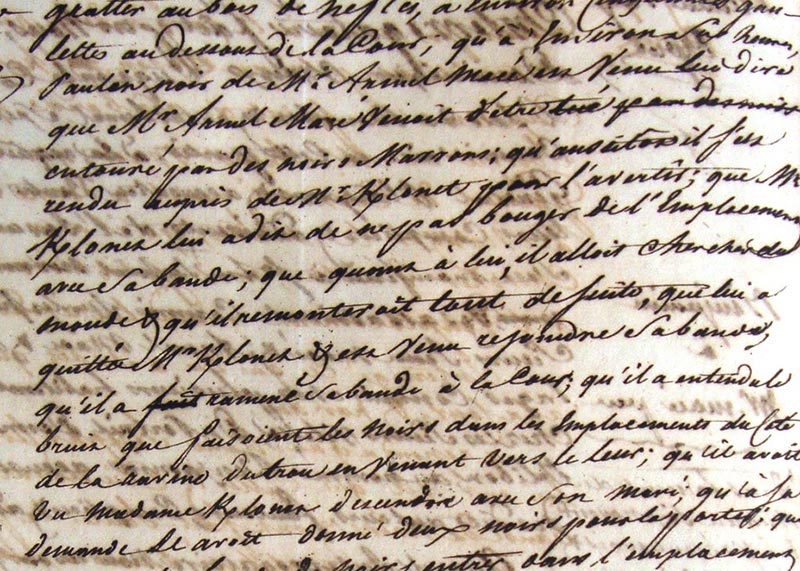

Around 7 in the morning, Paulin, an African belonging to Mr Macé, came to tell him that Mr Armel Macé had just been surrounded by fugitive slaves, and that he immediately went to warn Mr K/Lonet; that Mr K/Lonet told him not to move from where he was with his men and that he would get reinforcements and come at once… that he had seen Mme K/Lonet going down with her husband; that he had given her two Africans to carry her…

This statement made by Benjamin also confirms the fact that the masters decided to flee to safety.

Parfait, an African slave, was arrested in possession of two pistols, that he declared to have obtained from Mr Caro, who had given them to him to be used by the group of slave-hunters. He also declared:

“when he saw the crowd (the band of Africans), he did not think they were privately-owned slaves, but took them to be fugitives.”

One of the important events of the revolt was the deferring of several slaves on the estate of B. Hibon :

“Gilles and Elie came with a band of Africans and broke down the door of the main house, … they deferred Bastien, Joson, Zéphirin and Elie.”

When questioned by the prosecutor concerning the motives behind their being placed in the dungeon of the mansion, they replied: “because they had remained fugitive for three weeks, they had been chained up for about one month.”

Very few houses were pillaged, no buildings were set on fire and there were no acts of violence committed against free women. Only two brothers of the Macé family, attempting to prevent the insurgents from entering their houses, were killed.

Direct confrontation between the insurgents and a group of armed landowners, white or coloured free men, supported by faithful slaves, took place in a deep river-bed.

As the whites still possessed a minimum of firearms, they soon had the upper hand over the slaves, whose only arms were assegais (spears), axes and two stolen guns. Several dozen slaves died during the combat, close to 150 were captured, then imprisoned, either that day or on the days that followed. They were judged, sentenced and then executed in March 1812.

Following the revolt and the ensuing repression, it was noted that a number of slaves escaped from their plantations. In the 1812 censuses, several owners declared their slaves to be ‘criminal’ or that they were ‘to be judged’. It is also mentioned that some slaves had been ‘fugitives for seven months’, which corresponds to their escaping in November 1811.

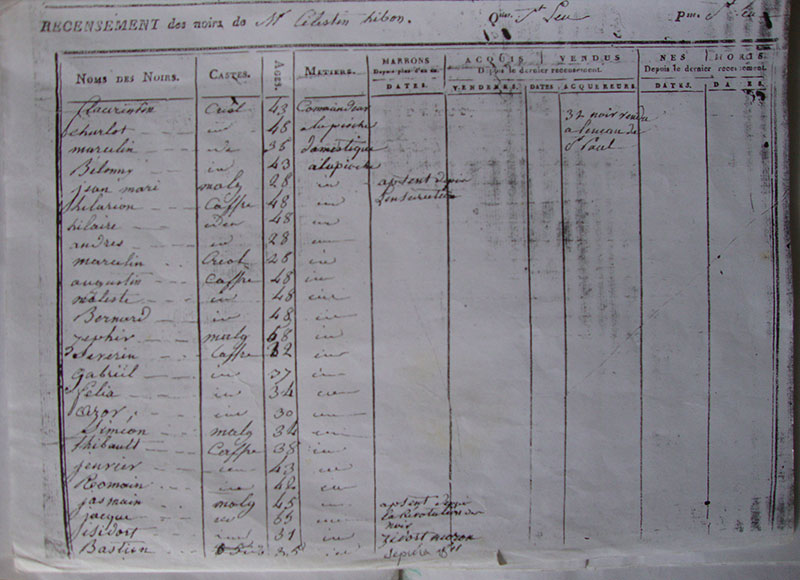

On the estate of Célestin Hibon, where Elie had been a slave and where the movement was largely initiated, prepared and implemented, after the revolt, six slaves, Africans or Madagascans, were declared to be ‘fugitives since the revolt’.

Another element indicates a link between the revolt and escape: the nature of the repressive measures. Fugitives who were pursued were often executed and not brought back to their estate. Slave hunters, to justify their activity, would bring back either the ears or the right hand as proof of capture.

This dismembering of the human body, these amputations, represented a lack of respect for the physical integrity of the dead person. With the decapitations carried out on those condemned to death following the revolt in 1811, the human body was once more dismembered, again with parts of the body being displaced. Jasmin and Géréon, executed in Saint-Denis, had their heads transported and most certainly exhibited in St Leu, undoubtedly with the aim of intimidating other slaves.

Finally, we can note that women slaves, involved in the revolt or as fugitives, were always in a minority, an indication that the forms of resistance they preferred more often concerned the family structure.

Elie and his three brothers were decapitated and their mother was arrested and interrogated. Gilles and his father died during the revolt, while his mother and sister were also imprisoned, then released.

A single revolt during a period of close to two centuries of oppression, while several thousand slaves became fugitives, indicates the control the masters had over their servile workforce. Individual actions, such as escape, were more easily carried out.

The revolt was finally unsuccessful and very often escape took on a temporary character.

While the revolt itself lasted only a few days, in early November 1811, and covered a fairly limited area, geographically speaking – the slopes above Saint Leu – it must be seen against the background of the time taken to prepare it and the geographical area initially intended. In addition, its impact on the white population was such that for several decades it greatly contributed to instilling fear among the population of free citizens then, after abolition, was the object of total denial and historical deformation.

Its was the whites themselves who, when speaking of the revolt, used the terms of ‘war’ and ‘Black revolution’, an indication of the traumatic character it represented for the free population and the political importance of the movement.