Yet their names float over the island’s peaks: Héva, Raharianne, Marianne, Sarlave, Simangalove. These women played an essential role in the fugitive society, participating in the life of the camps, as well as in the transmission of traditions, knowledge, beliefs and cultural and religious practices and rites. They made an important contribution to the island’s racial mixing and the discovery of the cirques.

The colonial presentation of the island’s fugitives has often – wrongly – been of individuals perpetually on the run in the island’s most remote and still unexplored spots. History shows us that they actually took root, set up true networks and settled on the island’s territory. They set up organised camps and ensured their protection against attacks from the detachments. They were true nomads who organised forays into the plantations on the coast in order to bring back women who had remained there as slaves and to replenish their stocks of tools and food.

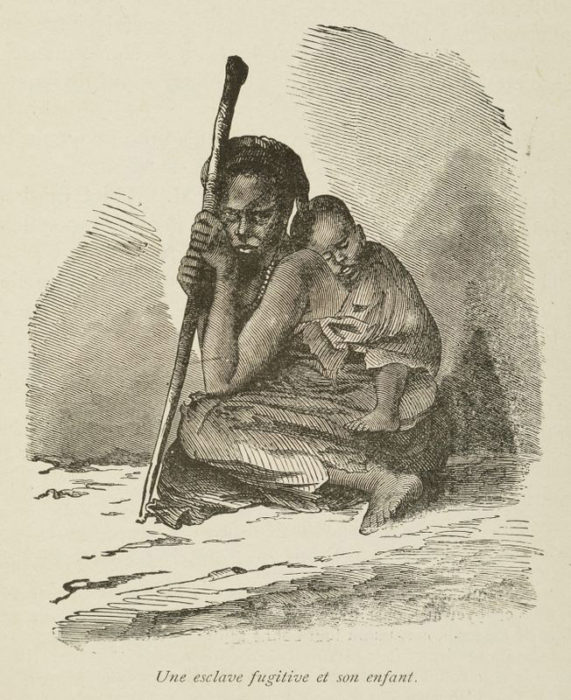

Reduced to slavery on his master’s plantation, the African / Madagascan was dispossessed of his family, his identity and his environment. In his quest for liberty, he expressed the desire and the wish to rebuild a family circle and create a new identity for himself in a new territory. Today, it is impossible for us to differentiate legend and reality. Whether or not these fugitive women existed, certain literary texts, accounts and documents from the archives tell of their existence alongside their companions and trace the lives of certain legendary fugitive couples.

There is no mention of this particular couple in any document in the archives. However, the peak of Piton Enchaing in the cirque of Salazie bears the name of the fugitive who lived there. The story of the Héva-Enchaing couple is considered as a founding myth, at the origins of the fugitive society. However, in the collective memory, Enchaing seems to have been forgotten, far behind the emblematic fugitive Mafate, to whom history has, unfortunately, not attributed a companion. According to the texts of Auguste Vinson, C.H. Leal and Eugène Dayot, Enchaing was apparently a non-violent fugitive slave, living peacefully and self-sufficiently on his peak. He is thought to have been the island’s first fugitive and had eight daughters with Héva, none of whom were ever enslaved. Each of the eight daughters married a great fugitive chief, thus producing the dynasty of the island’s great fugitive chiefs. They lived alone in their camp, where Héva took care of the ajoupa (hut), while Enchaing would go in search of food in the vicinity. Enchaing came from Madagascar, but we have no information concerning the origin of Héva.

Cimendef, a fugitive originally from Madagascar, is said to have lived with a certain Marianne. On the map of Reunion, the ridge prolonging the mountain chain of Cimendef in the cirque of Mafate is named after him. The writer Boris Gamaleya named Cimendef’s companion Raharianne, a Madagascan name, thus giving her a Madagascan identity. It was very common for women fugitives to be called Raharianne or Marianne, so it is difficult to find traces of Marianne/Rahariane, companion to the fugitive chief Cimendef. In C.H. Leal’s text, Marianne is a warrior who fought against settlers alongside her companion Cimendef. The role she played was not the same as that of Héva. According to J.M. Mac-Auliffe, Marianne was the companion of a great fugitive chief named Fanga, who had set up his camp in Cilaos. She was killed by the slave-hunter Edouard Robert. In a document from the archives dating back to 1751, the slave hunter François Mussard killed Raharianne, beloved of the fugitive chief Maffack (Mafate) at la Rivière des Galets, so Mafate is said to have had a certain Raharianne as his companion. Mafate, a fugitive originally from Madagascr, was a powerful sorcerer who had already been in contact with the French during the colonisation of Madagascar. He used to systematically question the sikidis (healers / sorcerers) concerning the future of the group of fugitives.

According to an account by C.H. Leal, Simangalove was the companion of the fugitive chief Matouté, living in a deep cave in the Trois Salazes in the cirque of Cilaos. Described as being a warrior and adviser, she was the eleventh chief of the group of fugitives combatting the colonial power.

The great king Laverdure and his queen Sarlave were feared by the colony’s detachments and constantly pursued by them. Their camp, in Ilet Marron, was in the cirque of Cilaos. Sarlave is said to have been killed by the slave hunter François Mussard in 1752 . Collective memory has not retained the name of this fugitive couple. However, the name of the fugitive chief Dimitile, geographically close to the camp of Sarlave and Laverdure, remains anchored the imagination of the island’s inhabitants.

Can this woman be considered as a fugitive? She was accused of providing material support for fugitives. Firmin Lacpatia drew inspiration from police reports drawn up in 1846 , recounting her story in his book ‘Adzire ou le prestige de la nuit’. She provides an example of the how an African woman could play a double role in the colonial society of Reunion, being a slave on the plantation and having dealings with fugitives.

A large number of fugitive chiefs left their mark on the island’s toponymy, such as Dimitile, Sémitave, Bâle and Pître, thier names figuring in the reports drawn up by the detachments, but history has not linked them to any women companions.

When the fugitives’ camps were attacked by slave hunters, more often than not the women were captured, since they were an important source of information for the settlers, concerning the composition of the camps, existence of other camps etc. The men fugitives were often killed. After being baptised, they had their right hand or head cut off as proof of their capture, enabling the hunter to receive a bonus. The hands and heads were then nailed up at the ‘customary place ’, as a warning and to dissuade any other slaves from planning to escape from the plantation.

It is to be noted that historical accounts tend to present the phenomenon of fugitives salves as essentially a masculine affair, in the same was as colonisation. We might imagine that when a slave escaped and decided to reconstruct a family in the inaccessible mountains of the island, he wished to protect the women from the colonial power by making them invisible. This would explain why the names of the women fugitives do not figure in the island’s toponymy. Consequently, we can suggest that according to the practices and customs of the fugitives, whether the latter were of African or Madagascan origin, only the men gave the territory their name or a word connected with their own identity.

In the accounts and archive documents related to fugitives, there is no doubt about women being a source of motivation and quest for freedom. They would encourage, prepare and help the men slaves to escape from the plantation and very often they then went to join them. They thus contributed to the survival of cultures, beliefs, religious practices and rites from their native country: music, food and knowledge of the natural environment. Essentially African and Madagascan, the women fugitives were responsible for racial mixing in the island’s cirques.

The island’s legendary female figures of Mme Desbassyns (plantation owner) and Grandmèr’ Kalle (a witch-like character), as well as women healers or tisaneurs (herbal healers) on Reunion, such as Mme Visnelda, inherited the characteristics attributed to women fugitives. The healers, thanks to their knowledge of local plants, appeased diseases of the body and spirit. Granmèr’ Kalle had the power of life and death and her spirit wanders in the island’s mountains. The spirit of Mme Desbassyns is thought to burn eternally in the fires of the Piton de la Fournaise volcano.

Slave, master or fugitive, these female characters are mingled and confused in these myths. The phenomenon of fugitives was, it is true, a quest for freedom, but also and above all a true story of love between the African men and their women.

Dayot, Eugène. Bourbon pittoresque ; poèmes (poems). Nouvelle imprimerie Dionysienne : Saint-Denis, 1977.

Gamaléya, Boris. Vali pour une reine morte. Regional council of Reunion. 2nd edition. 1986.

Lacpatia, Firmin. Adzire ou le prestige de la nuit. Editions Orphie: Paris, 1988.

Leal, Charles Henry. Un voyage à la Réunion. General Steam Printing Company, 1878.

MacAuliffe, J.M. La prise de Cilaos par François Mussard in Bourbon pittoresque ; Cilaos pittoresque et Thermale : Guide médical des eaux thermales. Azalées éditons: Saint-Denis, 1996.

Payet Marie-Ange. Les femmes dans le marronnage à l’île de la Réunion de 1662 à 1848. L’Harmattan: Paris, 2013.

Vinson, Auguste. Salazie ou le piton Anchaine, légende créole. Delagrave : Paris, 1833.