Even such a succinct summary reflects an exceptional social status and destiny for a woman of the 19th century, when they were generally excluded from most fields of activity, reserved for men. The main role of women during that period was that of spouse, ‘lady of the house’ and mother, responsible for bringing up the children. As soon as she took over the running of the estate, she decided to extend it and succeeded in making it prosper, despite a serious economic crisis . However, her notoriety in Reunion is due more to the legend constructed around her person than to her biography.

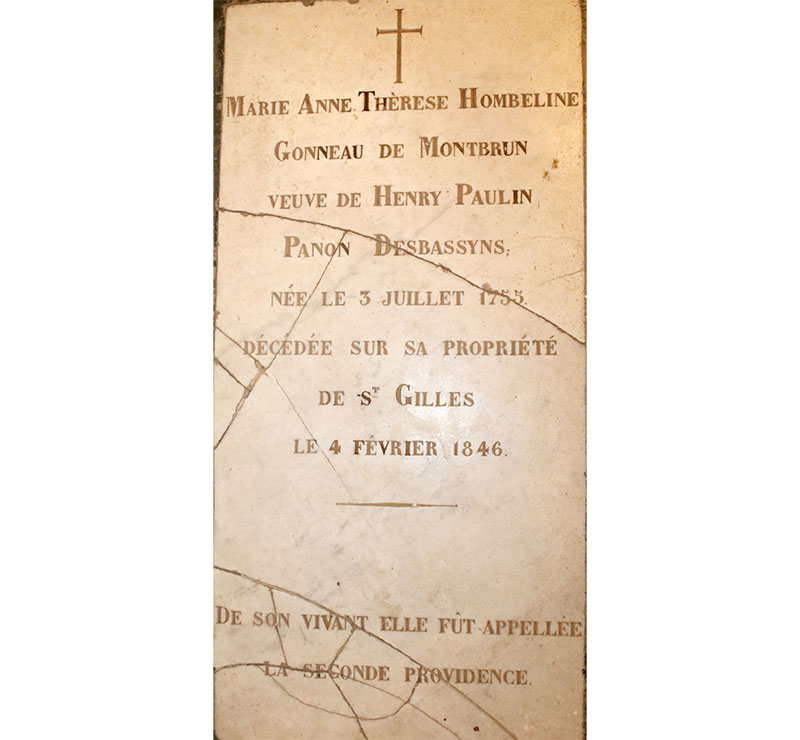

Madame Desbassayn’s life did not, however, begin under the best auspices. Her father was Julien Gonneau, a farmer in the mountainous area above Saint-Paul and her mother died giving birth to her on 3rd July 1755.

We know little about the person who brought her up: Jeanne Raux, her maternal aunt, married to Jean-Baptiste Hoareau a gendarme (military policeman), officially appointed as the child’s legal guardian on 20th May 1757 .

We know even less about her childhood and adolescence, except that, according to one of her grandsons, nicknamed Petit Gascon, “she had a perfect education, but virtually no instruction.” Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, her son-in-law, was more circumspect, declaring her education to have been “somewhat neglected”: reading, writing and arithmetic taught by the parish priest and a retired member of the army . During her adulthood, she seldom wrote and when she did, she tended to do so phonetically, but all this appeared sufficient for her to support Henri Paulin Panon-Desbassayns, the man she married on 28th May 1770, when he was aged over 38, and she was not yet 15.

It was after the death of her husband, on 11th October 1800, that she apparently came into her own, revealing qualities that attracted the admiration of all those who knew her. In August 1813, during a short stay in Mauritius, she was a guest of the new governor general of British India, on a visit to the island, according to whom “her manners reflected the elegance of high society, associated with the assurance brought by the practice of management ”.

In the Notice biographique he devoted to her in 1846, Jean-Baptiste de Villèle noted that she possessed “a capacity for administration that even the most experienced men might be envious of.” As regards Petit Gascon, he was content to declare that his grandmother “had long ago forgotten that she was a woman and was certainly possessed of a greater degree of the virility than the men around her ”. He always remembered her dressed in “simple widow’s weeds”: a black skirt, a white blouse and on her head a white kerchief covered with a brightly-coloured chequered Madras cloth.

In 1817, in addition to the image of her running a business, Auguste Billiard, who visited her, was struck by that of “a good mother, surrounded by half a dozen of her children and grandchildren” . Between 1818 and 1820, Théophile Frappaz, a ship’s lieutenant, another traveller hosted by Madame Desbassayns, also drew a laudatory portrait of her: “this respectable lady enjoys the highest consideration of everyone on the island, which she owes less to her great fortune than to her estimable qualities ”. Frappaz also wished to know how she was perceived by her slaves: “I shall never forget the expression of satisfaction and love on the faces of her many slaves when they spoke of their good mistress, whom they referred to as their mother.”

There is nothing that can lead us to doubt the sincerity of the naval officer and the reality of the various declarations he recorded. However, in view of her high social standing, the short period he spent on the estate and the language problem he most certainly encountered, it is difficult to conceive of the traveller strolling around the estate alone and chatting freely with the workers in the fields. His contacts were most probably limited to the slaves working in the yard or those chosen to be presented to him. Certain domestic staff, for example, were sometimes closer to the masters than to their fellow workers, and would not have taken the risk of losing the meagre privileges they enjoyed through expressing the least criticism concerning their owners. All these elements lead us to express serious reserves, not regarding the good faith of Mr Frappaz, but concerning the reliability of his sources and the answers he obtained.

In any case, Madame Desbassayns was the object of a true golden legend, behind her nickname of Second Providence which, during her lifetime, was given to one of the streets in the town of Saint-Paul.

The origin of the legend was the role she played during the attack on Saint-Paul by the British in 1809, when she saved the town from destruction. It must also be noted that in 1817, she donated her property situated at le Bout de l’Étang (Saint-Paul) to the sisters of the order of Saint-Joseph de Cluny, so that they could set up the island’s first school for girls in that town, although the establishment only welcomed children of free families, not slaves.

After her death, nourishing and consolidating her gilded image, she was ascribed with all possible virtues and her image was highly magnified, and at times liberties were taken with historical truth. Such was the case of the false notion of her managing her immense properties single-handedly. In actual fact, immediately after the death of her husband, she took on Jean-Baptiste de Villèle (1780-1848), her future son-in-law, to administer her property. In 1822, it was her son Charles who took over this responsibility and became the person mainly responsible for turning the estate in Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts over to sugar-cane, even though, faced with his over-enthusiasm for sugar cane, she restrained his zeal and continued to set aside part of the land for food crops, notably maize.

In 1809, though she did indeed contribute to saving Saint-Paul from destruction, the role she played was apparently less glorious than that put forward by Jean-Baptiste de Villèle in his funeral eulogy . According to him, the British did not carry out their threats because Madame Desbassayns had hosted and treated kindly their officers, previously taken prisoner, and they acted in recognition of “the care and consideration that they had been shown.” In actual fact, the destruction was avoided because the French General des Brulys, governor of the island, arrived from Saint-Denis with reinforcements and did not launch the counter-attack. At the request of a delegation of notables from Saint-Paul, owners of property in the town, he agreed to capitulate, before committing suicide . He was married to one of the nieces of Madame Desbassayns and the latter owned a residence close to his headquarters. It was certainly not solely out of affection that the family of Madame Desbassayns always surrounded the widow and her children, showing them her “their close attentions ”.

In 1841, the construction of a private chapel on the estate, the Chapelle Pointue, reinforced the image of her as a generous social benefactor. Today, it is difficult to measure the importance that the creation of a Catholic place of worship represented at that time. Independently of the true nature and depth of their religious faith, 19th-century settlers constantly relied on the services of the priests, who brought them together every Sunday for mass, at the same time giving them news of the island, the town or the surrounding area. The priest was responsible for christenings, confessions, weddings and funerals. People’s daily lives were marked out by the sound of bells and the celebrations on the liturgical calendar. They would go to church to pray, but also to get together, enjoy some time out and mourn their dead.

It was in the light of such considerations that the inhabitants of Saint-Gilles-les- Hauts certainly appreciated Madame Desbassayns’ contribution when she constructed the chapel. At the time, the action could be seen as the creation of a local public service, reinforcing her image as Second Providence. Intentionally or not, she was thus able to appease feelings of frustration and jealousy, as well as the hostility of those who had seen her extending her estate and building up her fortune at their expense. As the religion aimed to moralise the inhabitants, and more particularly the slaves, it was also a way of making her work-force more docile and respectful of authority. The intended effects were beneficial mainly to Madame Desbassayns’ estate, which she wished to hand down to her heirs in as prosperous a condition as possible. She was over 85 years of age when she had the chapel built.

In any case, the nickname and the legend attached to Second Providence turned her into a virtual saint. It is therefore not surprising that she became the object of a counter legend in reaction to this image, particularly when slavery was abolished and its full horrors came to light. This counter legend seems to have been born around 1910, or over half a century after her death, as a result of a rumour: it was said that she would use the blood of her slaves for the manufacture of construction mortar. The stories spread when the labourers working in the yard of her house along Chaussée Royale in St Paul saw that the mortar mixed to cement together the stones that had been used to build the old kitchen was reddish in colour.

The political and electoral context of the period was propitious to the circulation of such rumours. As from the end of the 19th century, with the creation of a secular and anticlerical republic in France, the de Villèle family became the target of those in power, who considered them to be enemies of the people. The descendants and heirs of Madame Desbassayns, they belonged to the clerical monarchist group, their combat in support of the religion becoming a political issue. In 1906, one year after the French law that was passed separating the Church and the State, Jean-Baptiste de Villèle (1852-1917) founded the journal La Croix du Dimanche (the Sunday Cross), with the aim of combating republicanism, presented as a movement wishing to destroy Catholicism.

It was also during this period that references to skin colour and slavery made their way into political discourse, noticeably when Lucien Gasparin, a member of the French parliament and a descendant of freed slaves, elected in 1906, went over to the side of those wishing to demolish the local aristocracy. The local press had a field day, reporting and indiscriminately exaggerating words or accusations of either side. As an example, on 20th January 1909, the newspaper Le Peuple published a letter written by a reader, who wished to remain anonymous, denouncing “the aristocrats of this country, who yesterday would take the whip to our ancestors and who today only dream of one thing: the death of the child and the return of slavery.” On the 26th January of the same year, the same newspaper commented on the results of the election and the small number of votes obtained by a candidate who was referred to as: “the democratic republican candidate Dager, a worker, Dager the black man.” In its 11th February 1910 issue, the paper Le Nouveau Journal de l’île de La Réunion denounced the behaviour of the electoral candidate Gasparin who, in their opinion, raised “the question of colour”, thus reviving “half-sleeping passions”.

Far from the world of politics and its partisan media, another element reflects the fact that Madame Desbassayns did not leave behind only good memories. It concerns a study published in bulletin N° 4-5 (1921-1922) of the Academy of Reunion island. The document was entitled Locutions et proverbes créoles (Creole expressions and sayings) and, to illustrate the definition of the word: cipèque (chipie or, in vulgar terms, bitch), the work gives, as an example, Madame Desbassayns, described as being “an authoritarian and cruel person […], a very vicious lady for her slaves.”

For a long period, the dark legend of Madame Desbassayns was not widely disseminated among the population, since it spread orally or was mentioned in texts which were seldom read. Thus, until the end of the 1960s, the legend was totally unknown to many families in certain districts of Saint-Paul. At the time of her death, it fell into oblivion and seemed set to remain as such. Already in 1866, the transfer of her ashes to the Chapelle Pointue went totally unnoticed. The same can be said for the centenary of her death in 1946, just like the centenary of the abolition of slavery in 1948. It is true that the latter was not mentioned in schools, where the pupils continued to learn about their ancestors, the Gauls. It was not that an effort was made to force such ideas onto them, but simply that the school textbooks used on the island were the same as those used all over France.

It was mainly in the 1970s that people started to mention Madame Desbassayns, through oral accounts ‘transmitted by former slaves to their descendants’, accounts recorded between 1976 and 1978 by an ethnologist and by two history students of the University of Reunion. They all referred to her as a spiteful and cruel woman, a psychopath who apparently spent most of her time causing misery for the slaves and committing sadistic crimes: the incarnation of absolute evil.

The exaggerations and historical inaccuracies contained in these accounts are in themselves sufficient for us to question their reliability: they tell of the organisers and denouncers of a plot whom she had thrown into the deep gorge of the Ravine à Malheur, the underground dungeons that she flooded in order to drown wrongdoers in groups of 15, the men that she had buried alive, the women she forced to give birth into a hole or the black babies given to the pigs as food, etc.

While the historians emphasise the unreliable character of the oral accounts obtained and the absolute necessity of obtaining multiple versions in order to be able to carry out the essential cross checks and comparisons, here, there is no mention of the total number, even approximate, of the persons questioned. We counted only ten or so, duly named or identified by their initials. Despite this very limited and thus insufficiently representative corpus, the transcribed accounts are presented as being an expression of popular common sense and examples of oral tradition.

However, we must avoid coming to the conclusion that negative accounts of Madame Desbassayns in the memories of the descendants of her slaves were totally inexistent. After 1848, a large number of them left her former estate as quickly as possible and the image they retained of her was far from positive. Many of them certainly suffered from the strict discipline that reigned on the estate: rigorous organisation based on constant mutual surveillance, repeated checks on work accomplished, punishments that could go as far as being locked up in prison or chained up.

It was her son Charles, who administrated the estate after 1822, who had established the harsh discipline, while continuing to manage his other properties, including the one in Sainte-Marie, where he lived . In Saint-Gilles-les-Hauts, where Madame Desbassayns remained omnipresent until the end of her life, she appears to have been sole mistress of the estate and certain slaves may well have hated her to the point of transmitting their negative feelings to their descendants. Jean-Baptiste de Villèle himself recognised her as having been extremely severe . The legend thus took its root in reality.

If the dark legend of Madame Desbassayns developed so easily after 1970, despite the exaggerated and implausible character of the accusations made, it was because the period was propitious to its dissemination. The 1960s saw the birth of a political movement focused on identity, which denounced the limitations of departmentalisation (Reunion becoming a French department), adopted in 1946 as a move to decolonise Reunion. The movement claimed the status of autonomous region for the island . The electoral elements at stake were obvious: extolling the memory of past suffering, generated by the servile structure of the society and of colonisation, at the origin of existing inequalities and discriminations. The 1960s was also a decade during which historians were greatly influenced by Marxism, a process reflected in the emphasis on economic factors and social antagonisms.

In this context, the history of Reunion was practically reduced to that of slavery: slavery was seen as a starting point, closely associated with the notion of the search for roots, the duty of memory and the cult of ancestors. Consequently, oral accounts given by the descendants of slaves were presented as privileged, even sacred, historical documents.

The large number of works or articles devoted to slavery is revealing of the interest in and popularity of the topic by researchers and members of the public during that period . As from the 1970s, Madame Desbassayns was also the object of studies or articles which reactivated the dark legend of her as an authoritarian woman devoid of humanity. Storytellers, singers and other local artists who talked about her generally believed they were expressing the reality of the person concerned. In actual fact, deliberately or unconsciously, they nourished, amplified and spread her legend. Today, any woman who, rightly or wrongly, is criticised for being too authoritarian in her professional capacity, is systematically assimilated with the person of Madame Desbassayns.

All this is largely due to an over-simplification of the society based on slavery, with, on the one hand, the black population, continually chained up and beaten, and on the other hand the ‘Gros Blancs’ (rich white people), necessarily evil, with Madame Desbassayns presented as the archetype. In fact, it is now recognised that she was not the owner of the island’s largest fortune, since as from the 1830s, hers was largely overshadowed by that of Gabriel Le Coat de Kervéguen (1800-1860), who possessed more slaves than she did. We also know that during that period everyone on Reunion island who could afford to do so, whether they were white, of mixed race or black, possessed slaves, sometimes just a small handful, who worked the land or were employed as domestic staff. The effect of giving her the implicit role of scapegoat results in the tendency to forget all the other lesser-known slave-owners and absolving their descendants of any possible exactions committed by their ancestors.

It is as though, in the absence of any liberator the likes of Toussaint Louverture on Haiti, it is Madame Desbassayns who, by crystallising all resent around her person, has the role of assembling the descendants of slaves in Reunion and perpetuating the memory of slavery.

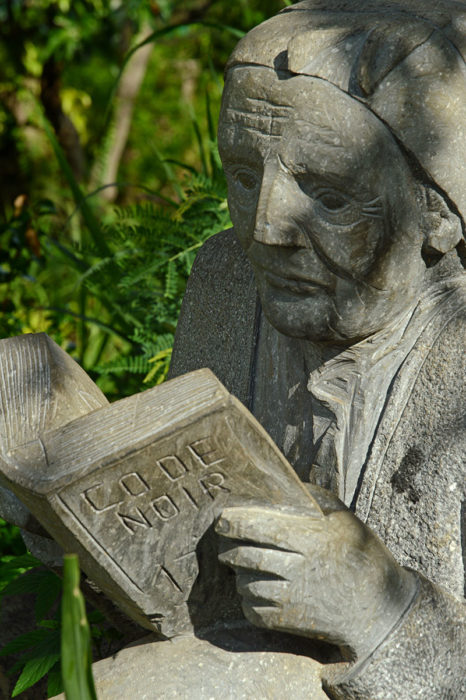

It is still possible that new elements may be discovered, but, to this day, there exists no convincing argument in favour of one or other of these two theories. A critical examination of extremely diverse documents that we consulted shows that she was a daughter of her period, both product and actor of a certain type of society . The economics of her estate depended on slavery, an inhuman and highly reprehensible practice, but which was, at the time perfectly legal and strictly regulated.

Like the majority of company directors who, yesterday or today, are seldom philanthropists, her aim was to take full advantage of the system, while at the same time improving its efficiency. Each of her actions or facets of her character naturally gave rise to all sorts of interpretations and representations in the 19th and 20th centuries, reflecting the mentalities and values of the periods in question and giving rise to legends anchored in the imagination of a large number of people on Reunion Island.