The concession was initially granted between 1674 and 1678 by the governor d’Orgeret to Jean Julien, born in Lyon around 1674. He was a former soldier enlisted by the French East India Company in Fort Dauphin. With his Madagascan wife, he settled on the windward coast, where he began to work the land he owned in Sainte-Suzanne, which was confirmed as being his property in 1703 and where he raised a few head of cattle and some poultry.

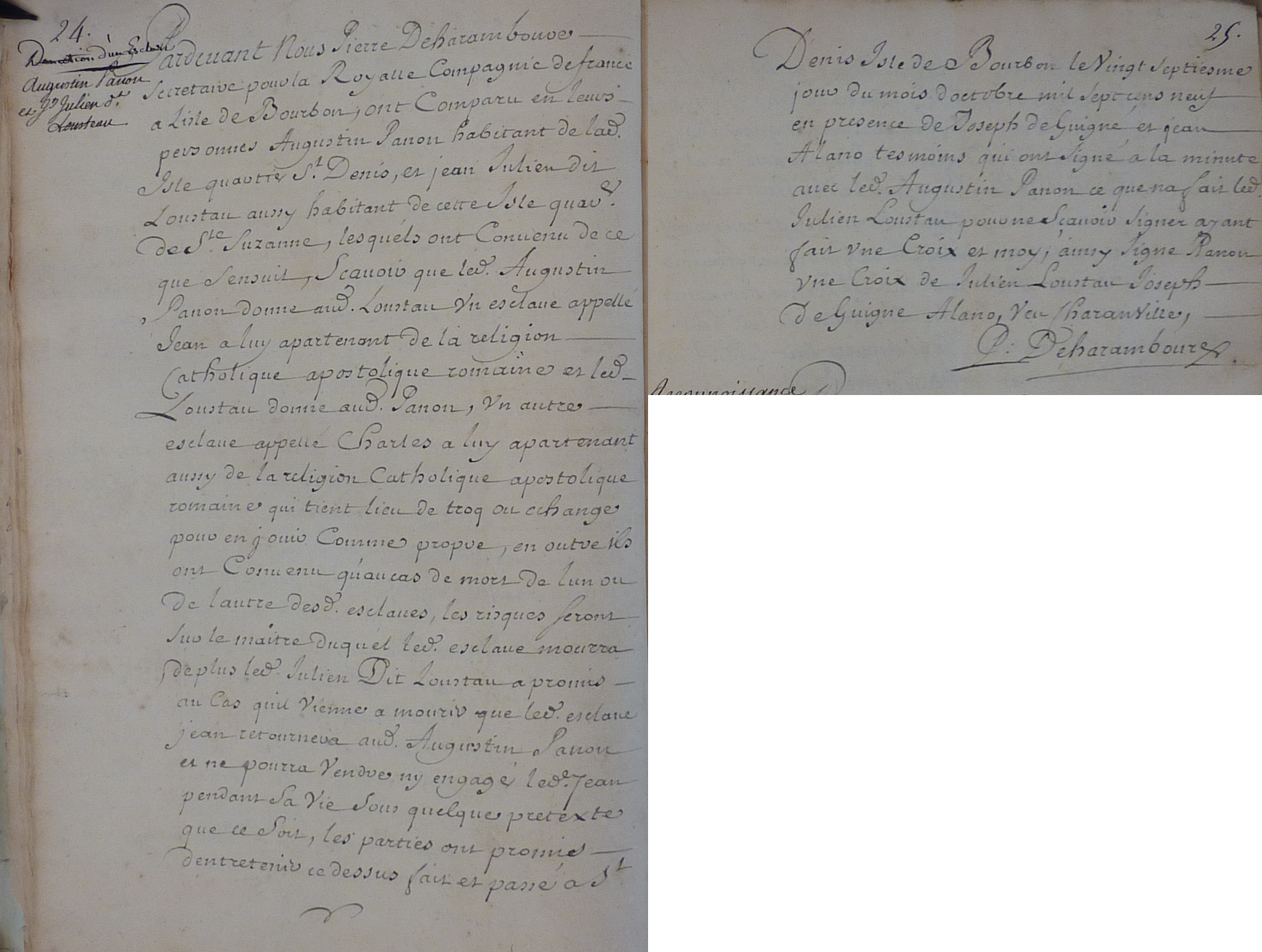

Throughout his period, there were slaves working on the estate and contributing to the development of le Grand Hazier. Charles, a slave originally from India who arrived with Jean Julien and his wife, was certainly the first slave to work on the concession of le Grand Hazier. In 1709, Jean Julien exchanged Charles for one of the slaves belonging to Augustin Panon. His work and close knowledge of the estate were apparently greatly appreciated by his new owner, recently arriving from Toulon , who had acquired half of Grand Hazier estate a few years before. Jean Julien, whose wife had recently died and who was growing old, was no longer able to take care of the upkeep of his land and decided to entrust the growing of crops on the estate to Augustin Panon.

Following the death of Jean Julien in 1714, Augustin Panon, a former journeyman now working as a house carpenter and joiner, who had acquired half of the estate ten years before , became the sole owner of the concession, which stretched from the gully of Grand Hazier to that of Jean Bellon and from the south of grand chemin as far as Bagatelle .

The ancestor of the Panon dynasty built his fortune by acquiring several concessions, and in particular le Grand Hazier, where he actually never lived, preferring the estate of La Mare, where he constructed the colony’s most beautiful mansion . On his estates, he grew wheat, rice, millet, sweet potatoes, a small amount of sugarcane as well as various fruits and vegetables. In 1710, he owned over 250 animals.

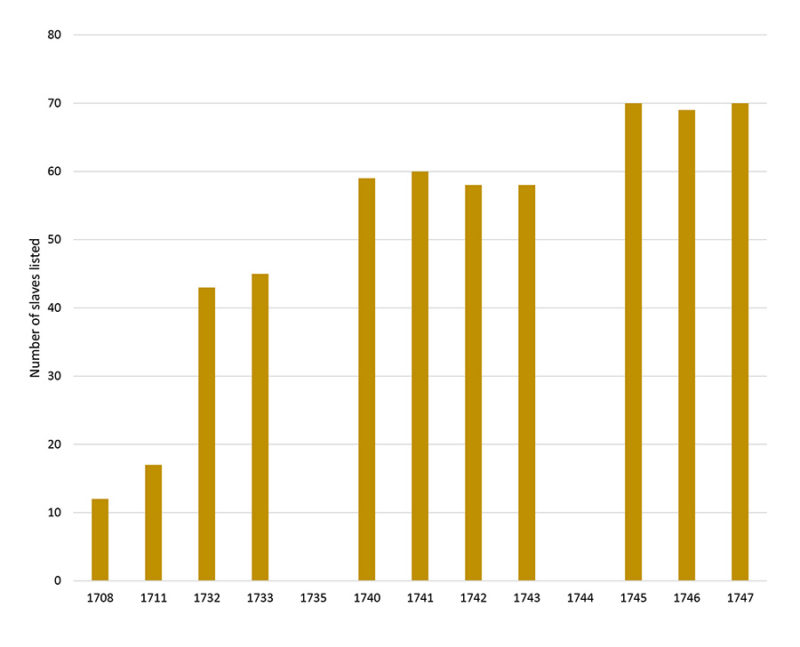

A large number of slaves were employed on the estates of le Grand Hazier and La Mare, enabling Augustin Panon to plant 22,000 coffee bushes on the 1751 acres of land belonging to him.

Desforges-Boucher who came back to the island in 1723, insisted on the island’s settlers having their estates marked out, which, notably, enabled him to impose taxes according to the amount of land they owned. The concession of le Grand Hazier, acquired by Augustin Panon almost 20 years previously, at the time measured over 62,000 square ‘rods’ or 147 hectares. In 1730, at the death of his wife Françoise Châtelain, the estate, all of which was acquired jointly, was divided between Augustin Panon and the 10 children she had with her four husbands. The nine surviving children each became owners of a plot measuring approximately 12 ha and Augustin Panon was granted a plot measuring approximately 110 hectares. As from this period, certain branches of the Panon family took on the family names of Panon Lamare and Panon du Hazier, the latter most probably being the owner of le Grand Hazier, showing how well-known this exceptional estate they had become. Others took on the names of Panon du Portail, Panon de l’Inde and Panon Desbassayns.

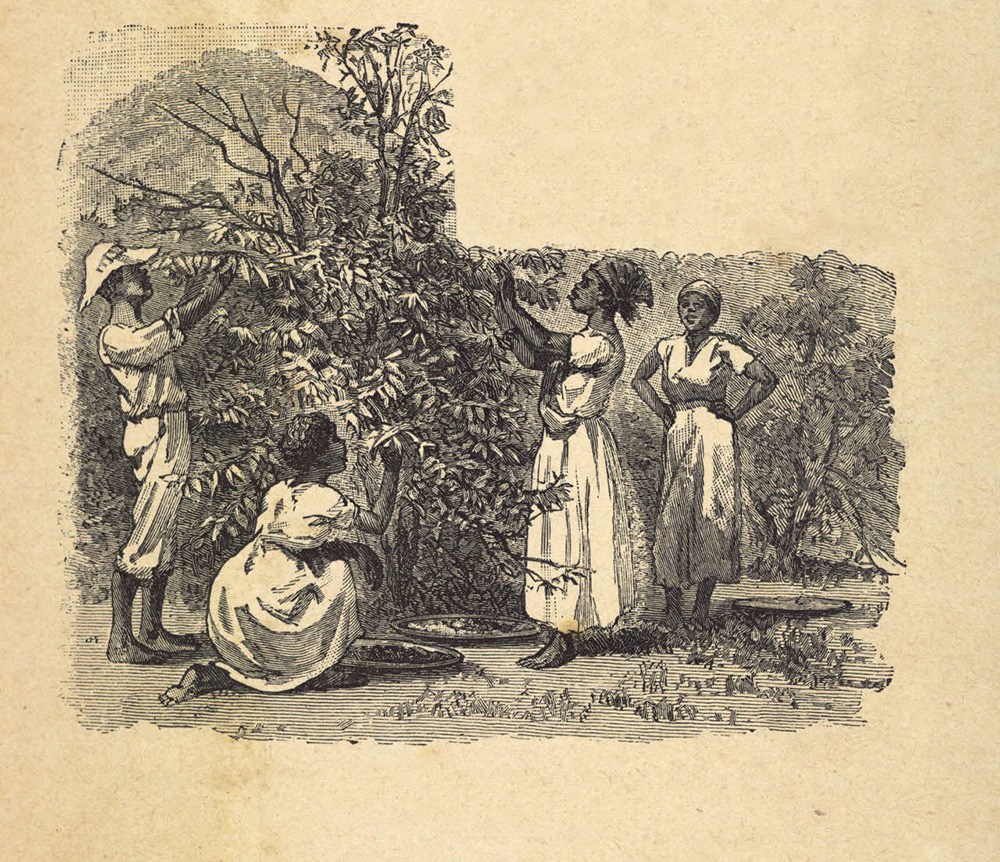

As from 1715, when the boom of Moka coffee arrived on Bourbon island, members of the Panon family and their heirs actively participated in developing this crop, encouraged by the island’s Council. In 1741 , Augustin Panon declared 32 000 coffee plants, Louis Caillou, husband of Panon’s daughter Catherine declared 29,000, while Jean Louis Gilles François Desblottières, husband of the youngest daughter Marie, declared close to 40,000. When Bourbon island was transferred from the French East India Company to the King of France, the situation on the island became concerning. The coffee plants were seriously damaged by three destructive cyclones in 1772, 1773 and 1774. The large-scale landowners took advantage of the precarious situation of smaller-scale owners, who had lost their entire crop, to acquire additional land. The wealth of a landowner was now measured not only according to the area of his estate, but depended above all on the number of coffee plants and number of slaves. Coffee growing, which necessitated a large workforce, led to the beginnings of a large-scale slave trade.

Around 1785, the landowners settled in the locality of le Grand Hazier were called Grinne, Gillot, Panon l’Inde , Sentuary et Delaunay . With the exception of Grinne, they were all heirs of or otherwise connected to the Panon dynasty. Jean Jacques Panon l’Inde is without any doubt one of the least known of Joseph Panon Lamare’s children. An officer of the troops in Pondicherry as from 1736, his spent entire military career in India. He entrusted the management of the land he owned in le Grand Hazier to his nephew Pierre Auguste Delaunay, already owner of a neighbouring plot.

However, it was only after 1789 that Nicolas Caradec, one of Delaunay’s heirs, truly developed the estate of le Grand Hazier. Coming from Brittany, Caradec, of noble birth, was a former officer who had fought at Pondicherry. He married Madeleine Gillot , the daughter of a rich landowner. He planted maize, rice, wheat and cassava on the estate, as well as coffee and cloves.

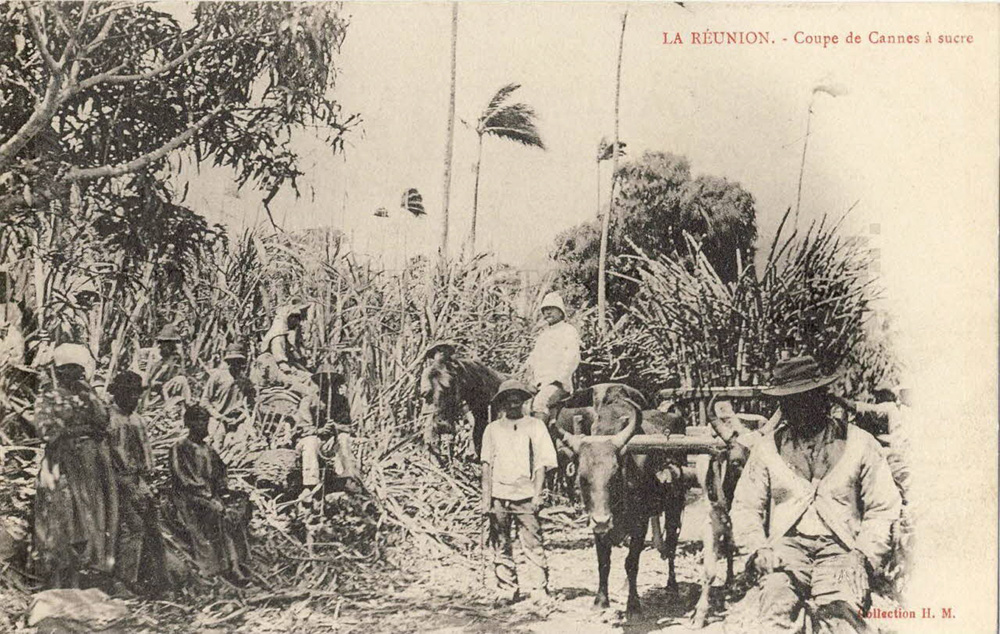

When Caradec died in 1813, the estate covered close to 52 hectares. His widow more more or less abandoned the growing of food crops to take up the challenge of sugarcane and construct a sugar factory, probably before 1830. She received the support of members of the Nas de Tourris family, who inherited the estate when the widow died in 1843.

The number of slaves working on the estate in the early 19th-century had more or less remained the same since 1747. When Nicolas Caradec’s widow and the Tourris family took up the challenge of sugarcane and constructed the sugar factory on the Grand Hazier estate, they needed to increase their workforce, despite the law that now banned the slave trade , Fifty slaves, including 20 or so young ‘blacks’ were listed in the inventory drawn up following the death of Marie Nicolas Gustave de Nas de Tourris.

Le Grand Hazier was more particularly developed by the son of a settler from Brittany, a certain Jean Baptiste Marie Zéphirin Martin Renoyal de Lescouble who, from 1811 to 1838, gave an account of his life on Bourbon island . We should remember that at the time la Grand Hazier was seen as just a place-name rather than as an estate in its own right. It was in this context that from 1811 to 1813 Lescouble lived on the property belonging to this half-brother Grinn, not far from that belonging to Caradec . The neighbours with whom he had friendly relations were called Caradec, Grinne an the widow Fréon .

The main house, constructed at the time of Caradec, was built in timber, with a shingle cladding and panelled. It was relatively modest, but already built to the standards applied to the Creole houses belonging to important landowners: a two-storey house with a veranda, sitting-room, dining-room and outside kitchen. It was constructed facing the large group of huts housing the slaves and adjacent to the ‘calbanon’ constructed around 1848. The house being dilapidated, the Nas de Tourris family had it reconstructed around 1860. It was later bought by the Chassagne family, who are the current owners.

After 1859, a large number of the indentured workers needed for growing sugarcane were affected by the cholera epidemics. Louis de Nas de Tourris, at the time mayor of Sainte-Suzanne, was particularly attentive not only to the health of the workers on his estate, but also to that of the population of Sainte-Suzanne. His diligence during this difficult period led to his being granted the title of Knight of the French Legion of Honour and being honoured by Emperor Napoléon III himself . The resulting crisis led the Creole planters to find other sources of income to compensate for the drop in sugarcane production.

The Governor Darricau asked Louis de Nas de Tourris to travel to New Caledonia to explore the idea of planting sugarcane and constructing new factories there. On returning, convinced that he had found the new El Dorado for sugarcane, Louis de Nas de Tourris sold the estate and left with his family, followed by other Creole e state owners who also left for New Caledonia, taking with them a certain number of Indian employees, specialised in the growing of sugarcane .

Adolphe Richard and his wife Marie Eugénie Deshayes bought the large estate from Louis de Nas de Tourris and in 1876 added to it the estate of Belle Eau, located to the north of Grand Hazier. Adolphe Richard also took over from Louis de Nas de Tourris in his position of first magistrate of the town, a post that he held until he died in 1885. His wife outlived him by five years, but due to the complexity of the inheritance, it took a certain time for the estate to be handed down.

At the end of the century, le Grand Hazier was marked out and surrounded on all sides by estates belonging to the heirs of the widow Jurien, who was none other than Camille Panon Desbassayns de Richemont , the descendant of Augustin Panon, owner of le Grand Hazier at the start of the 18th-century.

This area close to the coast was for a long time covered by forest, but the trees had virtually all been cut down by this time. In addition to the crops covering the 120 ha of the estate, the forest was replaced by a number of orchards: lychees, mangoes, June plums, breadfruit, avocados, Indian almond, palms, coffee, mangosteen etc., all fruit trees marking out the seasons and filling the estate with their sweet scents . Thirty person were employed to tend to the crops on the estate.

Having died without leaving any direct descendants, despite her three marriages, Marie Eugénie Deshayes left to her twelve heirs a number of estates to be sold, scattered all over the island. In 1894, le Grand Hazier was purchased by Ernest Vinson , déjà propriétaire du domaine de La Convenance already owner of the estate of La Convenance and of a property along the chemin des Magasins in Sainte-Suzanne . He preferred to live on his estate in Sainte-Marie, leaving Marie Joseph Vincent de Paul Féréol Eugène Lépervanche to manage le Grand Hazier. As he also had no direct heirs, his many heirs sold Grand Hazier and a number of other properties for financial gain. The company Lépervanche & Cie purchased the estate and then sold it to Albert Chassagne in 1903.

Albert Chassagne, trained as an engineer, was the descendant of family arriving in Reunion from Bordeaux in 1825. He purchased le Grand Hazier after managing the sugar factory of Quartier-Français. In 1899, he was managing the establishment when it was destroyed by a devastating fire which, notably, led to the death of Tristan de Bernardy de Sigoyer, the warden of the distillery, as well as two of his daughters, who had tried to save him. Tristan de Bernardy de Sigoyer’s third daughter , Marie Josèphe Léonie Benoîte, married Albert Chassagne in 1900.

As from 1911, Albert Chassagne decided to reconstruct the house which had been built by the Nas de Tourris Family and which was in poor condition. The innovative character of the reconstruction is a reminder that Albert Chassagne had trained as an engineer and had many exceptionally interesting ideas. Metal roof beams and septic tanks were soon brought into the island, as well as window-panes, cast iron pipes and various other materials, which could now be bought locally. From the start of the 20th century, in addition to sugarcane, he started growing ylang-ylang, vanilla and several other food crops such as cassava, maize and peas.

A long alley lined with Madagascan palm trees on either side leads up to the main house. Under the ownership of Albert Chassagne, the orchards were improved, planted with extraordinary trees and species of exceptional diversity . Walking through the shady orchards is extremely pleasant: they are planted with screw pines, wilds pineapples, palm trees, cocoa bushes, banana plants, breadfruit etc. There is a very large diversity and the list is far from exhaustive. There is also a vegetable garden of 2,000 square metres with sweet potato, aubergines, cassava, maize and purple yams, as well as more common species such as lettuce, turnips, onions and carrots. Turmeric, Thai limes, chilli peppers and ginger have not been forgotten: all essential ingredients for the preparation of local curries .

After the death of Albert Chassagne, in 1947, his widow and children set up a Real Estate company, which is still in existence. One of Albert de Chassagne and Léonie Bernardy de Sigoyer’s great-grandchildren has once more started growing sugarcane on the estate of le Grand Hazier. A company involved in vanilla production has also been set up on the spot of the former stables, and a large number of tourists come to visit the infrastructure and obtain information about the techniques of vanilla production.

ABALAIN, Hervé, Le français et les langues historiques de la France, Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot, 2007.

AUPIAIS, Damien, Les immigrants bretons à l’île Bourbon de 1665 à 1810, d’après le dictionnaire généalogique des familles de l’Ile Bourbon (La Réunion) de L.G. Camille Ricquebourg, Collection Mor Braz Editions, Edition JFR/Grand Océan, Saint-Paul, 2006.

AUPIAIS, Dominique, La part celtique dans l’héritage culturel et politique des comptoirs français de l’océan Indien, thèse de doctorat, Université de La Réunion, 2011.

BARASSIN, Jean, La vie quotidienne des colons de l’île Bourbon à la fin du règne de Louis XIV, 1700-1715, Cercle Généalogique de Bourbon, Saint-Denis, 1989.

BENARD, Jules et MONGE, Bernard, L’épopée des cinq cents premiers réunionnais, Dictionnaire du peuplement (1663-1713), Azalée Editions, Sainte-Marie (La Réunion), 1994.

BOUCHER, Antoine, Mémoire pour servir à la connoissance particulière de chacun des habitans de l’Isle de Bourbon, Editions ARS Terres Créoles, Saint-André, 1989.

BREST, Pierre et CARTON, Virginie, La Réunion dans la Grande Guerre, ONAC, 2017.

COMBEAU, Yvan, « De Bourbon à La Réunion, l’histoire d’une île (du XVIIe au XXe siècle) », Hermès, La Revue 2002/1 (n° 32-33).

DAGET, Serge, L’abolition de la traite des noirs en France de 1814 à 1831, les cahiers d’études africaines, vol. 11, N°41, 1971.

DEJEAN de La BATTIE, Antoine, Histoire Généalogique de la famille NAS de TOURRIS en Provence et à l’Ile Bourbon, Jules Céas & Fils éditeurs, Valence-sur-Rhône, 1934.

DELATHIERE, Jerry, L’aventure sucrière en Nouvelle Calédonie, 1865-1900, Société d’Etudes Historiques de la Nouvelle-Calédonie N°64, 2009.

DELATHIERE, Jerry, Ils ont créé La Foa, familles pionnières de Nouvelle-Calédonie, édité par la mairie de La Foa, 2000

DUPON, Jean-François, Les immigrants indiens de la Réunion. Evolution et assimilation d’une population. Cahiers d’outre-mer. N° 77 – 20e année, Janvier-mars 1967. pp. 49-88.

EGON, J.P, Connaissance de l’architecture réunionnaise, septembre 1983.

EVE, Prosper, Un Quartier du « Bon Pays », Sainte-Suzanne, de 1646 à nos jours, Océan Editions, Saint-André (La Réunion), 1996.

GÉRARD, Gilles, La famille esclave à Bourbon, Thèse de doctorat, Université de La Réunion, 2011.

GÉRAUD, Jean-François, maître de conférences, Kerveguen sucrier, Université de La Réunion.

GÉRAUD, Jean-François, Les maîtres du sucre, Ile Bourbon, 1810-1848…, Océan Editions, Saint-André, 2013.

GÉRAUD, Jean-François, LE TERRIER, Xavier, Atlas historique du sucre à l’Ile Bourbon/La Réunion (1810-1914), Océan éditions, Saint-André, 2010.

GOUSSEAU, Sylvie, « BEAUREGARD », une plantation de la côte au vent, fondation pour la recherche dans l’Océan Indien, 1984

HO, Hai Quang, Contributions à l’histoire économique de l’île de la Réunion (1642-1848), L’Harmattan, Paris, 1998.

JAUZE, Albert, Notaire et notariat, Le notariat français et les hommes dans une colonie à l’Est du Cap de Bonne-Espérance, Bourbon-La Réunion, 1668 – milieu du XIXe siècle, Thèse de doctorat en histoire soutenue en 2004, Editions Publibook, Paris, 2009.

LEVENEUR, Bernard, JONCA, Fabienne, Le Grand Hazier, un domaine créole, 4 épices éditions

LOUGNON, Albert, L’île Bourbon pendant la régence, Desforges-Boucher, les débuts du café, revue d’histoire, Paris, 1956.

LUCAS, Raoul et SERVIABLE, Mario, Commandants & Gouverneurs de l’île de La Réunion, Océans Editions, 2008.

MAZET, Claude, L’île Bourbon en 1735, les hommes, la terre, le café et les vivres, 1989, co-édition du Service des Publications et du Centre de Documentation et de recherche en histoire Régionale de l’Université de la Réunion

MERGNAC, Marie-Odile, Archives de notaires et généalogie, Editions Archives et cultures, 2015.

MERGNAC, Marie-Odile, Utiliser le cadastre en généalogie, Editions Archives et cultures, 2015.

MORIZOT, Joseph, Considérations historiques et médicales sur l’état de l’esclavage à l’île Bourbon (Afrique) suivi du testament de Madame Desbassayns, Editions Orphie, 2019

PANON DESBASSAYNS, Henry Paulin, Petit journal des Epoques pour servir à ma mémoire (1784-1786), Edité par Annie Laforgue, musée historique

RAMSAMY-NADARASSIN, Jean-Régis, Les travailleurs indiens sous contrat à La réunion (1848-1948), Thèse de doctorat, 2012.

RENOYAL de LESCOUBLE, Jean Baptiste, Journal d’un colon de l’île Bourbon, 3 volumes, L’Harmattan, Editions du Tramail, 1990.

RICQUEBOURG, L.J. Camille, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles de l’île Bourbon (La Réunion), 1665-1810, Patman printing, Pailles, Ile Maurice, 2001.

SCHERER, André, Guide des archives de La Réunion, Saint-Denis, Imprimerie Cazal, 1974.

SMIL, Yannick, Les spécificités du bornage à l’île de La Réunion et leurs origines, mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du diplôme d’ingénieur ESGT, Le Mans, 2002.

SPEEDY, Karin, Colons, Créoles et Coolies, L’immigration réunionnaise en Nouvelle-Calédonie (XIXe siècle) et le tayo de Saint-Louis, Editions L’Harmattan, Paris, 2007.

WANQUET, Claude, Histoire d’une révolution, La Réunion (1789-1803), tome I, Editions Jeanne Lafitte, 1980.